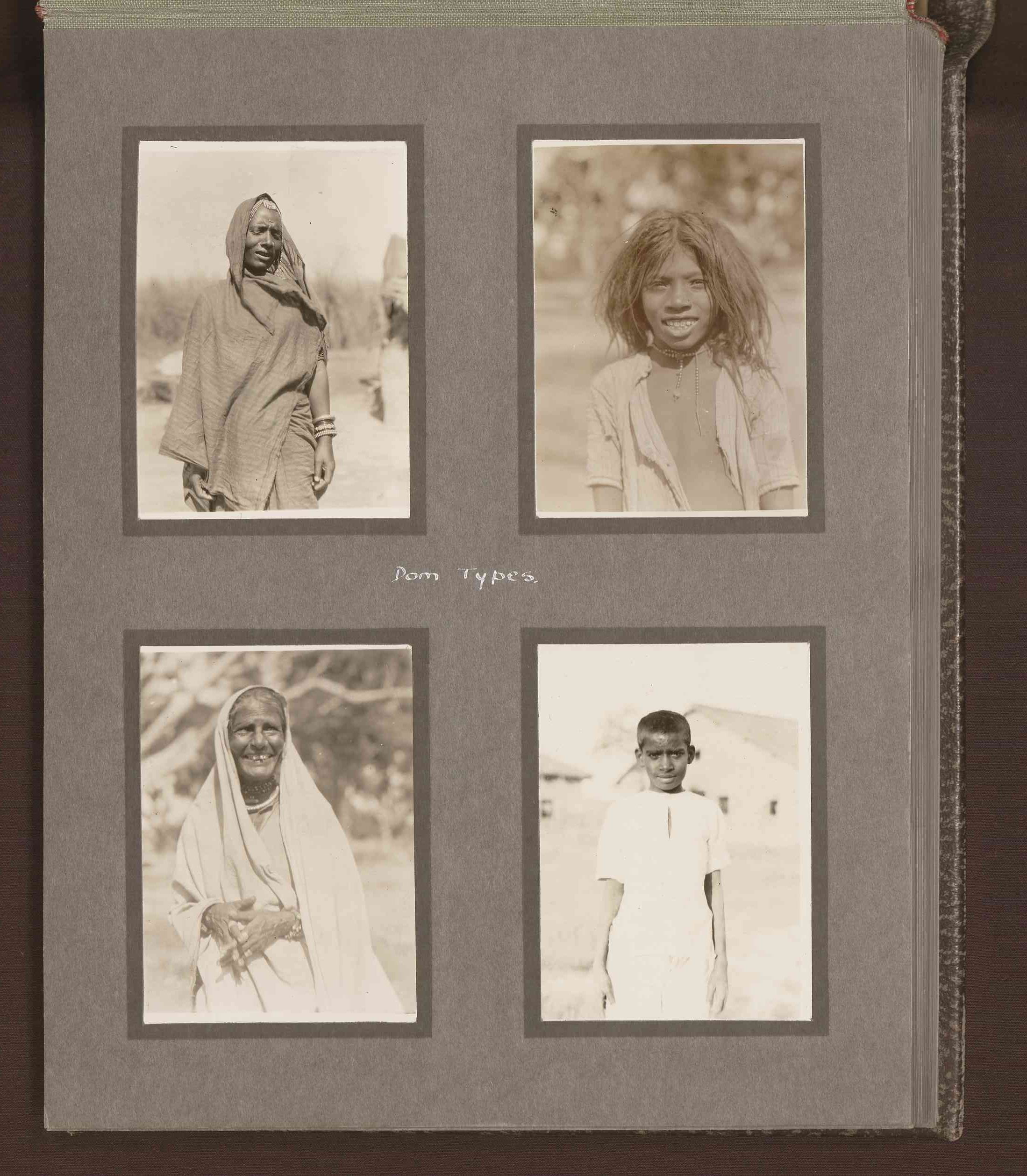

“Dom Types”

Charmaine Toh

Martyn Jolly has noted that photographic albums were both oral and visual records – their owners would show them to friends and family accompanied by an oral narrative.1 This oral element is of course now lost, but I raise it that we might recognize the importance of situating the individual elements of such archival material within a broader context. In the case of this album, it seems to have been put together to narrate Porter’s philanthropic efforts in India. It is certainly more “formal” in tone than the other Porter album in the archive, which includes photos of family and friends and even her pet dog. One can speculate that Porter would have shown the India album to raise awareness of the situation in India and perhaps to even persuade her audience to support more of such efforts.2 Martyn Jolly, “An Australian Spiritualist’s Personal Cartes-de-Visite Album,” in Shifting Focus: Colonial Australian Photography 1850-1920, ed. Anne Maxwell and Josephine Croci (North Melbourne, Vic: Australian Scholarly Publishing Pty Ltd, 2015), 71–72.

The page “Dom types” shows frontal portrait shots typical of ethnographic studies, as is the use of the word “types” in the caption.3 There are two portraits of older women and two portraits of young boys laid out in a grid format. The Dom is an ethnic group from the untouchable caste in India5 and both the visual and textual language is specific to colonial photography. Portraits of ethnic types were a key part of the colonial encounter, acting not only as tools of ethnology and anthropology but also to satisfy the desire of the British (and subsequently Australian) public to see exotic and unknown races.4 Photo studios would hold archives of such racial types for sale to tourists as souvenirs of their trips and it is possible that, rather than taking the photos, Porter bought them from a studio in India. The locals are depicted as observed objects and labeled as a genre – none have individual descriptions such as names or ages.

Critics of ethnographic photography often discuss how such portraits reinforce colonial power relations by reducing the colonized to distant objects. However, it is hard to reconcile such a reading with some of the individual portraits on this page. In particular, the young boy depicted in the photograph on the top right hand corner is full of personality. He is grinning into the camera and making direct eye contact with the viewer. Similarly, the lady depicted in the bottom left corner is also smiling into the camera; her hands actively held in front of her body instead of the usual pose of holding them stiffly along the sides of the body like in the other portraits. In both these photos, there is an intimacy and individuality that is quite unusual in ethnographic portraiture and a stark contrast to the remaining two photos.

Given what we know of Porter’s missionary work, she could have chosen such atypical portraits to suggest a shared humanity deserving of greater evangelical effort.5 The two rather charming portraits are even more unusual when we note the low social status of the Dom caste within its own country. As such, the presence of this page in the album could be read as legitimising the overall narrative presented by Porter – that of the white missionary helping the “natives”.

Charmaine Toh is a PhD candidate in the Asia Institute. Her thesis looks at visual imagination and pictorial photography in Singapore from the 1940s to the 1970s.

Citations

1 Martyn Jolly, “An Australian Spiritualist’s Personal Cartes-de-Visite Album,” in Shifting Focus: Colonial Australian Photography 1850-1920, ed. Anne Maxwell and Josephine Croci (North Melbourne, Vic: Australian Scholarly Publishing Pty Ltd, 2015), 71–72.

2 For an excellent discussion of the relationship between photography and ethnography, see Elizabeth Edwards, “Photographic ‘Types’: The Pursuit of Method,” Visual Anthropology 3, no. 2–3 (January 1, 1990): 235–58, doi:10.1080/08949468.1990.9966534.

3 Govind Sadashiv Ghurye, Caste and Race in India (Popular Prakashan: 1969), 8.

4 For a detailed discussion of such portraits, see Chapter 5 “Photographing the Natives” in James R. Ryan, Picturing Empire: Photography and the Visualization of the British Empire (Reaktion Books, 2013).

5 Prue Ahrens has noted that missionary photography is less about distance and knowledge and more about a shared humanity despite its use of ethnographic tools. See Prue Ahrens, “Ethnographic Pictorialism and George Brown’s Portraits”, in Shifting Focus: Colonial Australian Photography 1850-1920, ed. Anne Maxwell and Josephine Croci (North Melbourne, Vic: Australian Scholarly Publishing Pty Ltd, 2015), 179-180.

Leave a Reply