Vicarious communist: a reflection on the empathetic archivist

Adapted from a presentation given at the symposium ‘Bernie Taft and 1968: Tanks in Prague, Turmoil in Australian Universities’, Friday 24th August 2018 by Jane Beattie, Assistant Archivist, University of Melbourne.

To commemorate the 80th anniversary of the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 2016, I wrote a blog post about Lloyd Edmonds. Lloyd’s family donated his letters, written mostly to his father, from the battlegrounds in Spain. Lloyd was studying in London when Franco invaded and felt so strongly in the Republican cause, and that Spain should not fall to fascism, that he joined the International brigade, along with 64 other Australians volunteering in Spain. Soon after this anniversary, the University of Melbourne Archives (UMA) ran a tutorial for a Hispanic Cultural Studies class, introducing students to the Archives using Lloyd’s letters and other material held at UMA about the war.

Group discussion commonly came back to questions of motivation, and ultimately led to the personal reflection “how far could I go for my beliefs?” Expanding on this question brought up further discussions about other people who went above and beyond to uphold their values; female Australian doctors who were barred from enlisting in World War One, paving their own way to Europe to work with voluntary medical outfits, and more recent examples of the young people who left various countries to fight with and against ISIL. As I started processing the Bernie Taft collection late last year the same question began to resurface; “how far would I go to uphold my values and beliefs?”

The 107 boxes of the Bernie Taft papers that are now open for researchers illustrate not only the various narratives of the world communist movement but also the commitment of a man to his beliefs. Although I did not get the chance to meet Bernie, there is a certain familiarity. It is not an unexpected result of spending hours reading and describing the life of a person. Germaine Greer curator Rachel Buchanan labelled her section of the Dawson Street offices as ‘Greertown’ and whilst I am yet to call my colleagues comrades, there have been times when communism has been part of my dreams. As Rachel might agree, if you are not careful the person or subject being described can begin to take over how you view the world. Suddenly it seemed like communism was everywhere; I rushed off to see the film The Death of Stalin, became absorbed in the Ken Burns documentary series The Vietnam War, and probably spent a bit too much time discussing the Soviet Union, China and Hungary in conversations with friends.

Before describing the material in a new acquisition, the archivist must understand how the creator of those records used them, and how they arranged them in some kind of system. In archives speak this is the ‘original order’, and with Bernie’s papers, I had a bit of work ahead of me. He described material his many filing cabinets a bit like a to do list, a never-ending register of reading, re-reading, researching and reflecting. The arrangement is at times scattered but also charming. Bernie wrote notes to himself instructing that certain documents be taken on his travels to re-read. He also gave folders titles consisting solely of a date: a time frame in which he had to read material and then respond to a friend about its content. Multiple bundles of handwritten notes show a mind constantly thinking and planning. There are rushed notes scribbled on the back of pamphlets used during Philip Herington’s campaign for Brunswick, nearly always more passionate than the resulting report to the National Executive. Questions and answers to thoughts that just had to be written down at that precise moment, often on the back of an envelope or a scrap of paper; post it notes became breadcrumbs across decades of work.

These idiosyncrasies are reality for the archivist arranging and describing collection material. Diving deeply into records of a life means the archivist must confront the subjects that arise. Yes, the description of the record is made with objectivity and accessibility for research a top priority, however the imprint of those records onto the person is not objective. At times it can be overwhelming; I felt for colleagues working with the Red Cross POW cards and another Greer archivist who described letters from survivors of sexual assault. The profound and sometimes confronting nature of some of the material held in archives and other cultural institutions means archivists, researchers, and historians must care for their own mental health.

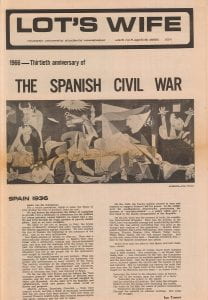

UMA ran the Hispanic Cultural Studies class again in 2018, and I was probably a bit too excited that I could add some items about Spain from Bernie’s collection. I had new material that I hoped would connect these students to Franco’s Spain from an Australian perspective. Monash paper Lot’s Wife for example, featured the 30th anniversary of the start of the Spanish Civil war for most of its April 19 1966 issue, and so students were also introduced to the university as a site of activism, and the role it can play in the political landscape.

Reflecting on the Spanish Civil War and then processing a collection that contains sobering information about the way people have treated each other throughout humanity’s timeline is confronting and frustrating. There is so much history to learn from, held in places like UMA, and yet the same kinds of issues and movements repeat. I will admit to times where I have brought melancholy home with me; a crushing attitude towards humanity and a desire to never pick up a newspaper again. But I am held back from going down that path, and it is because of Bernie. The records have at times pushed me to despair but it is the person who ultimately has the most affect. It is a key lesson. His collection shows the importance of not throwing in the towel, to toil, to treasure and to keep seeking to understand the workings of this world. In a letter to Heinz Timmerman on July 5th 1984 Bernie relates his movements after resigning from the Party and his optimism in creating a new socialist organisation writing “I believe it has a good chance of filling a vacuum in Australian political life which the Communist Party could not achieve.” It is this determination to keep trying to enact change that I found uplifting. Realising that one door closing, slamming perhaps, means that you can open a window and let a new breeze in.

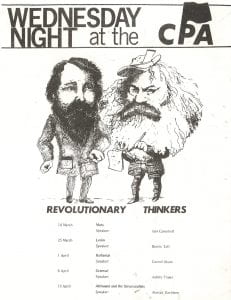

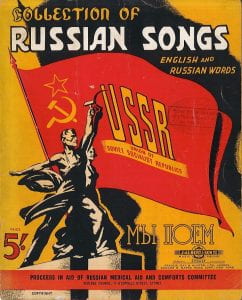

The publication of an online finding aid for researchers to navigate Taft’s collection is a win for study into Australian communism, the labor and trade union movements, and other interests of Taft’s such as Australian Jewish advocacy and socialist organisations. A significant amount of material from the Marx School and other CPA educational programs can be found, as well as material relating to CPA crisis of the 50s and 70s. There are also publications about communism and other political ideologies and figures, official CPA documents from Taft’s tenures in National Executive and Victorian State Committees, and as joint national secretary; researchers can key word search the full listing found here.

At the conclusion of this project and it is time to reflect on my learning as archivist and individual. In these past 8 or so months my personal politics have shifted, some beliefs rejected, others strengthened. I realise that my past knowledge of communism had been superficial, and so not only did I get to increase my professional skill but I got a free education in political history – I can say with all honesty that my understanding of the workings of this world got a little deeper and who can really say that in their profession? And so, what the public gain by having this collection open for use, the archivist does too.

Leave a Reply