An Aegean Adventure: Kellie Youngs on her Jessie Webb Scholarship

Research into glass and faience objects from Cyprus in the late Bronze Age involves more than digging into the ancient past. It also concerns the more recent past of the objects, as well as archaeological and museological practice. As part of my PhD project, I tracked down the present-day locations of various treasures, from elegant glass perfume bottles to sensitively modelled animal head rhyta, now held in a series of European museums. Financing a trip to Europe to visit these museums and study the objects in person, however, was a challenge. But in May last year I was excited to find I had been awarded the Jessie Webb scholarship to further my PhD studies by spending three months in Greece at the British School at Athens. The generous support of my supervisors, referees, mentors and family, and a good deal of hard work, brought about this extraordinary opportunity to go on a magical mystery tour through time, to explore the world of Minoans and Mycenaeans, palaces and precious objects.

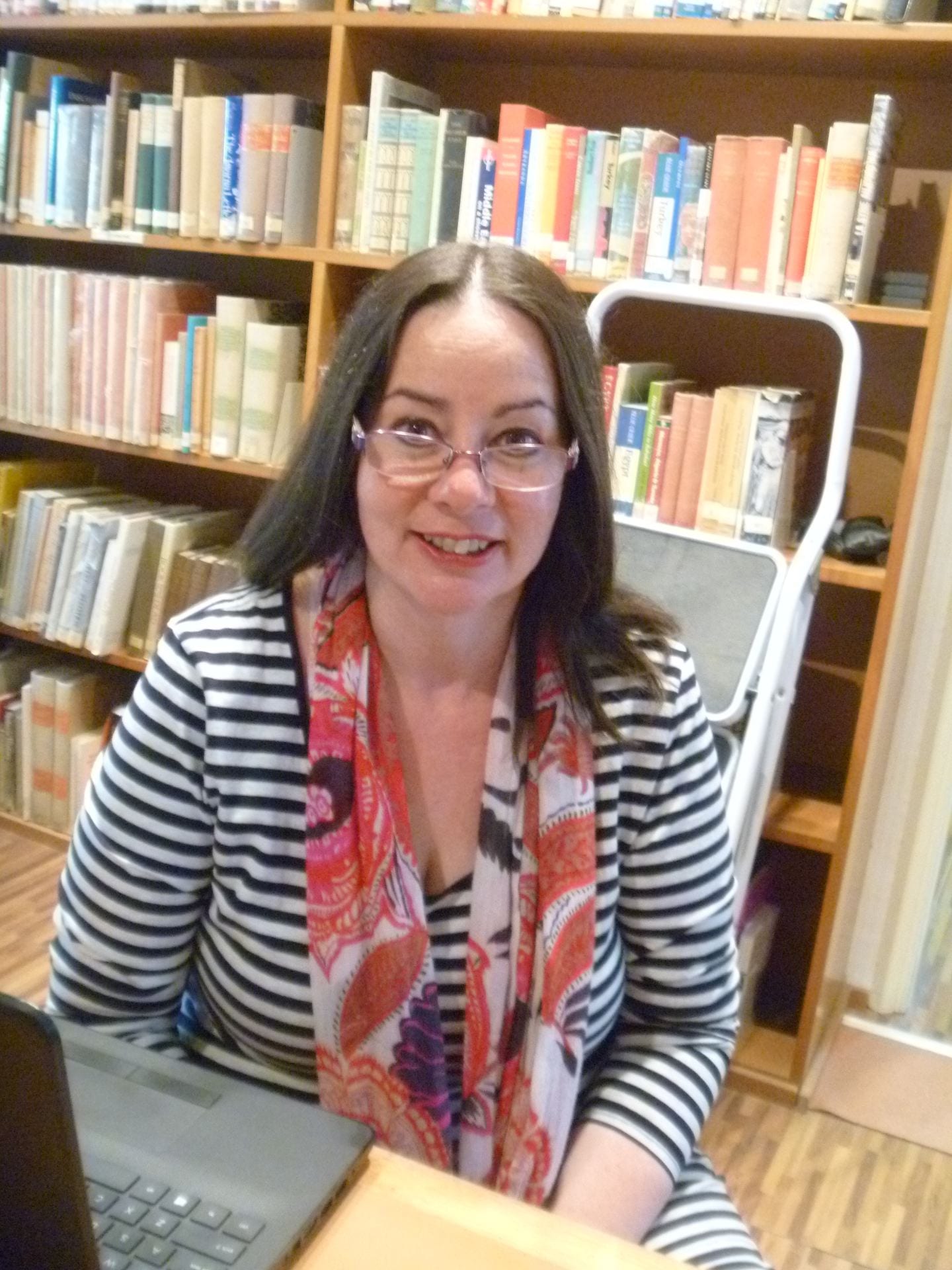

Kellie Youngs, resident at the British School in Athens and recipient of a 2018 Jessie Webb Scholarship, reflects on her research and time in Greece.

My Research Project

My PhD project examines the transmission and innovation of faience and glass technologies from Egypt, the Near East, and the Aegean to Cyprus in the Late Bronze Age. Faience and glass objects from this period are beautiful things, but I don’t study them just for their own sake. Technological choices made by ancient societies can also provide important insights into the socio-political, environmental, and economic-structural factors at work within those societies.

These objects are especially valuable when it comes to the Late Cypriot period. There was a script in use at the time that is not yet deciphered, so when approaching the Cypriot state, we rely to some degree on the written records of its neighbours. Vigorous scholarly debate surrounds the socio-political structures of Late Bronze Age Cyprus. There is an apparent disconnect between the high diplomatic status of Cyprus, as conveyed in diplomatic texts from Egypt and the Near East, and the contemporary material record, that presents as a dearth of material expressing formal governmental institutions. Production and distribution of luxury faïence and glass objects had a significant role in the materialisation of an ideology promoting political legitimacy by state and temple authorities in other regions with whom Cypriots had meaningful contact and was tightly controlled. The study of the Cypriot glass and faïence industries may thus provide an alternative way to examine expressions of central authority.

I am halfway through my PhD project and last year was devoted to examining the objects I had spent tracking down in 2017 through excavation reports and museum catalogues. From January to May 2018 I travelled to museums in Cyprus, Sweden, and Britain to compile a catalogue of glass and faïence objects originally found in Cyprus. Though earlier scholars have written about different glass and faïence objects from the island and considered which of those may have been made locally, there is no single comprehensive record of these objects and no firm view on the existence of a local industry. My aim is to create such a record to be made freely available as a web-resource and added to as additional objects come to light.

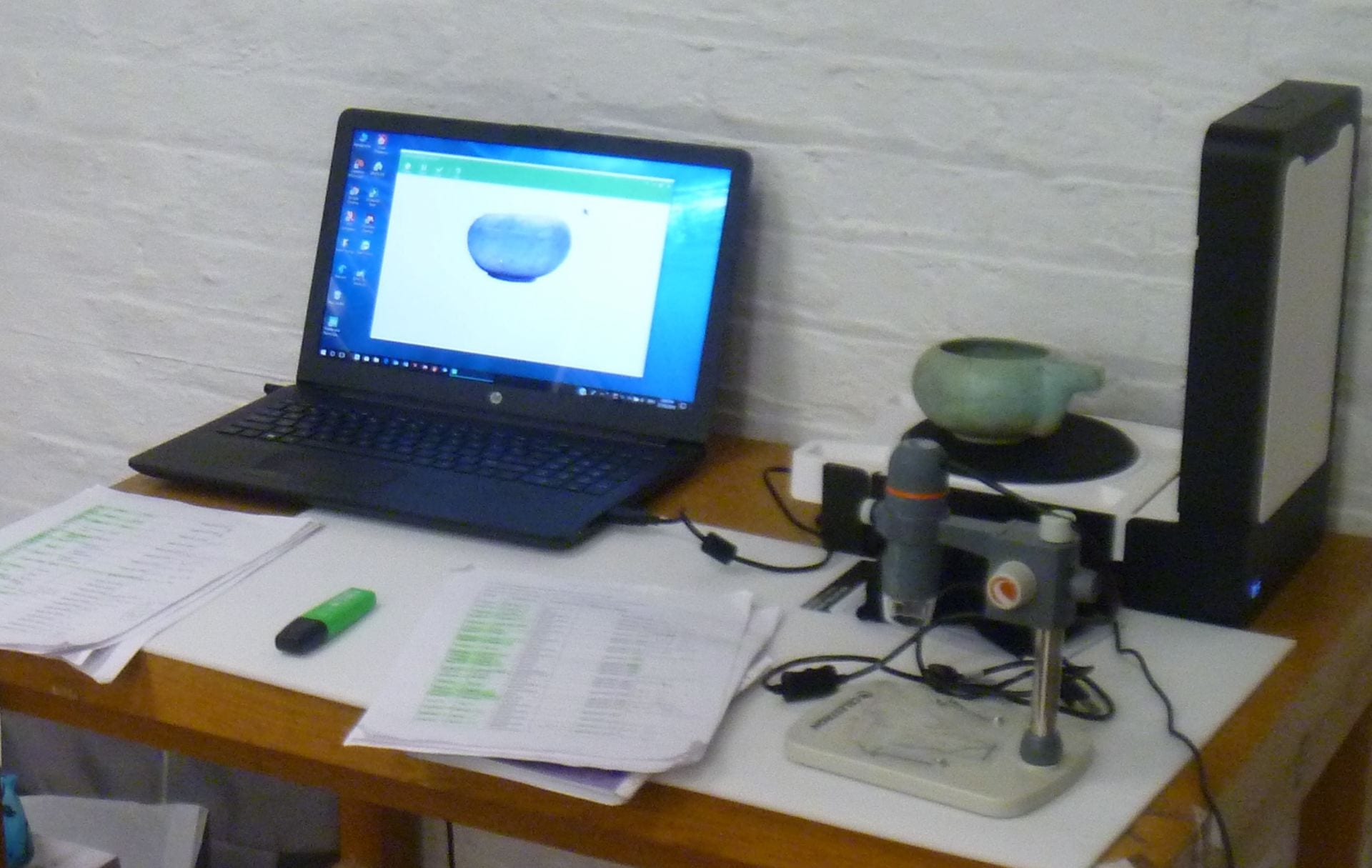

Using a portable scanner/camera, I have created a database of 3D images of Late Cypriot glass and faïence vessels for precise 3D comparison to identify distinguishing manufacturing signatures across the collections. These manufacturing signatures provide insight into what level of local production existed in Cyprus and how it was influenced by imported products and technologies transferred from neighbouring regions.

Faïence Ram’s Head Rhyton, [date]. British Museum, 1897.4.1.1212. 3D Scan by Kellie Youngs, 2018, with kind permission of British Museum. Film, 2018 © John J. Pollard, used with permission

My Research Trip to Greece

With the generous support of the Jessie Webb scholarship, I was able to arrange a second visit overseas, undertaking periods of residence in both Athens and Crete from November 2018 to January 2019. Vital to the successful completion of my project, these residencies allowed me to make comparative analyses of Minoan faïence manufacturing techniques and the development of the Mycenaean glass manufacturing industry with the corpus of glass and faïence objects found in Cyprus. Most importantly, I could see Minoan faïence and Mycenaean glass objects in the museum collections of Athens and Crete first hand, as well the glass making workshops excavated in Greece. Armed with this new information, I hoped to identify the origin of some objects imported to Cyprus, as well as sources of stylistic inspiration, and technological innovations transferred from Crete and Mainland Greece to Cyprus.

By closely examining and scanning objects in museums, I am developing a clarified typology. Many similar object types are described in radically differently ways in reports by the various archaeologists who excavated them at different sites over time. Consequently, it was very difficult for me to make connections between these objects and see patterns until I examined them in person.

Digital Aspects of My Research

Many of the objects I study came to light in excavations undertaken early in the twentieth century. One hundred years ago, the scientific method was in its infancy in archaeology. Practices were still rather loose and colourful, and many important aspects of archaeological context were lost due to incomplete and not entirely accurate reporting. Further, many objects were excavated, packed into crates and shipped to the homelands of foreign excavators without being seen by most Cypriots. Digital reintegration of this globally dispersed collection emerged as a possibility as I began processing data for my PhD thesis.

Armed with my trusty Matter and Form portable scanner, I have been to the great museums of England, Sweden and Cyprus to examine and scan Late Cypriot glass and faïence. My scanner is an Arduino-based, consumer-class scanner with an automated turntable. It simultaneously takes a laser scan to build an object mesh and uses photogrammetry to create a texture layer. The scanner has easy-to-use cleaning and editing software, which I used to produce 3D images that can be displayed in a variety of ways on 2D and 3D screens as well as for virtual reality (VR).

As my 3D scanner produces an image on the screen of the laptop while it builds the object, I have often found myself with an audience as I work in museums. Curators, museum staff, and visiting scholars have stopped to watch the scan take shape and talk about potential for collaborating and curating digital resources. As a consequence, I realised how my data could be used for more than just my own research. I could curate a virtual exhibition of objects dispersed across the globe. There are potentially great benefits for scholarly collaboration, as well as an opportunity to make this material accessible to a wider audience, particularly the general public of Cyprus, many of whom have no access to these objects because they are overseas and not even on display in many cases.

During my residency in Athens and Crete, these aspects of my research led to many great discussions and opportunities to demonstrate the operation of the scanner and my 3D images for scholars from all over the world. It was also a great icebreaker when I needed courage to open a dialogue with eminent scholars in my field.

The British School at Athens

Established in 1886, the British School at Athens (BSA) is a calm oasis in the centre of bustling Athens. The spacious grounds are wound with paths through fragrant gardens, dotted with attractive heritage buildings and surrounded by a high wall that keeps the frantic city at bay and protects and preserves a precious 130-year institutional history in its buildings, books and furnishings. The facilities in the residence are secure, comfortable, and attractive, providing the right balance between private and communal space. The community spirit fostered in the BSA residence is particularly valuable to me after the isolating experience of travelling and staying on my own for some months early in my international research journey. I was in Athens for Christmas 2018 and was glad my new friend and fellow scholar, Christina Ichim from Canada, was there to celebrate with me, making gingerbread shaped like cuneiform tablets and a Phaistos disc.

As I have travelled the globe on this research journey it has become clear to me that “it takes a village” to raise a PhD candidate. Staying at the BSA, I benefited from access to a much wider scholarly community who were generous with their time and thoughts and helped me bring greater context and focus to my research. It was such a privilege to live and breathe archaeology every day for three whole months. Not just my own archaeology, but a grand smorgasbord of the ancient world that comes from living with a dozen other scholars, each on their own research adventure. To rise and chat about the Iron age funerary practices of Samothrace at breakfast, discuss the strike functions of different shaped bronze age swords through lunch, and ponder the meaning of decorative motifs on an Egyptian kohl box with evening wine and cheese, is an endlessly exciting and inspiring prize beyond riches, and I am grateful for it every day.

The library is an excellent environment in which to work. It is particularly motivating to write surrounded by my peers and senior researchers. Access to the comprehensive collection has refined and enhanced my research and I regularly benefited from the research expertise, technical assistance and genuine kindness of the crack team of librarians – Penny, Sandra, Tom (and Bouboulina the cat). I have also gained a broader perspective of Aegean archaeology and had the opportunity to network with other scholars by attending the lectures and events held at the BSA and other schools, including the Swedish and American Schools at Athens. Of course, it is not all hard work. I have taken the odd afternoon off to explore the Acropolis, Agora, and marvellous new Acropolis museum. (There are also ice-cream breaks because I am an icecream-fuelled research machine!)

My residency at the British School at Athens, and the opportunity to develop my scholarly network contributed significantly to the development of my research and my future career in archaeology. Financial support through the Jessie Webb Scholarship has been vital in ensuring my project aims were realised in Greece and enriching my doctoral thesis. I am deeply honoured to be a beneficiary of the ongoing kindness of Jessie Stobo Watson Webb, a scholar who contributed significantly to the University of Melbourne and study of the Ancient world. I hope to do likewise. Having chosen the path of archaeological research, it is crucial to me that, building on the work of scholars before me, I contribute to new knowledge in my field and find innovative and effective ways to share that knowledge with other scholars and a wider, interested audience. I want to ignite passionate curiosity in people to know ourselves, embrace diversity, and foster compassion by exploring our ancient past.

I genuinely treasured my stay at the BSA, where I felt part of a unique extended family and had the chance to undertake a period of concentrated work, relieved of the usual demands of employment and family life. To the great village raising this PhD candidate, I give my most sincere thanks, especially my inspiring supervisors Professor Louise Hitchcock and Associate Professor Andrew Jamieson.