Hands-on Humanities: Bringing the Ancient World to Regional Victorian Schools

The study of classical antiquity and the ancient world more broadly has often been the exclusive domain of the privileged and leisured classes. State schools, especially rural ones, often lack the resources to provide their students with specialist instruction in these fields. Since 2016, Dr Sharyn Volk has been addressing this inequality through a project aimed at opening up the University’s Classics and Archaeology collections to secondary students in Victoria.

Often affectionately referred to as simply ‘The Goulburn Valley Project’, this program has given hundreds of teenagers a unique ‘hands-on’ introduction to the fields of archaeology and ancient history. In this blog post Sharyn explains why the project was created, how it works, and what future opportunities continue to unfold as the project evolves.

Multiple studies have shown that students at Australian rural schools face many levels of disadvantage. Geographic isolation, low socio-economic status, limited access to experienced teachers with the capacity to lead classes across a broad curriculum, and depressed student and parental aspirations – all these factors have a negative impact on student educational outcomes and life trajectories. The Goulburn Valley Project was developed in response to this situation. Specifically, we wanted to open up new horizons for rural secondary students through exposure to teaching methods, drawing upon the University of Melbourne’s unique collections of objects related to the ancient world.

The program was formulated within a hands-on-humanities framework – in other words, it centres on hands-on activities, giving students the opportunity to explore ideas by working with objects. This principle is a paramount element of the program’s design: hands-on activities are proven to engage students who are challenged by text-based learning as a function of their poor literacy skills. Participation in the program has achieved strong results, assisting in improving learning and retention outcomes, raising aspiration levels and promoting cross-cultural awareness.

Our project has now completed four successful years of delivery to five schools in the Goulburn Valley region: Kyabram Secondary College, Numurkah Secondary College, Mooroopna Secondary College, McGuire College, and Shepparton High School. Delivery will continue in 2020 (including to the new Greater Shepparton Secondary College, which will incorporate Mooroopna Secondary College, McGuire College, Shepparton High School and Wanganui Secondary College, into a multiple campus college).

The program is delivered at zero cost to the participant student families. It is offered to all students at Year 7 level, while students in Years 8 and 9 opt in voluntarily, based on their level of interest. In the first instance we visit the schools and spend a double period, around ninety minutes, with each Year 7 group. Later in the year, students from all year levels are offered the opportunity of a full day excursion to Melbourne. The willingness of the schools to allow their students to absent themselves from the scheduled timetable is testimony to their recognition of the program’s value.

The program has been designed to align with the Victorian History curriculum. For Years 7 and 8 the curriculum designates study of human communities across a chronological span of 60,000 BCE to 650 CE. Schools choose from a range of options, studying a mix of Australian, European and Mediterranean (Egypt, Greece, Rome) and Asia-Pacific societies (India, China). Some of our activities apply equally across all civilisations, while those that are specific focus on ancient Egypt. They engage with the historical concepts and skills specified by the curriculum, namely: sequencing chronology, analysing historical sources as evidence, identifying patterns of continuity and change, and analysing causes and effects including consideration of historical significance.

Object-based learning and teaching is a vital component of our hands-on approach. In one session, students are introduced to the life of a field archaeologist as a pathway to exploring how objects might leave their sites of deposition to reside elsewhere. This session affords the opportunity to explore the important concept of context; this is achieved through the use of a replica statue of Bastet, an ancient Egyptian goddess who takes the form of a cat. We ask the students: what might it mean if a cat statue is found in a bedroom? Alternatively, what if the cat is found in a temple? Bastet is a student favourite – easily capturing the imagination, she is an excellent catalyst for exploring potential meanings beyond the everyday.

The session prompts conversation about what types of objects a field archaeologist might find, and what could happen to these objects following completion of the site excavation. We explore the concept of classification and the knowledge which can be inferred from grouping objects into classes, including the potential for chronological sequencing. In our first hands-on activity, each student is given a bag of everyday objects such as lids, buttons, or shells. Students are asked to arrange their objects in whatever order they prefer. This might be according to colour, shape, material, age, use, or a combination of these attributes. We encourage discussion about who might have used the objects, how, and why. Each student is then given the opportunity to share their findings with their classmates, providing a forum for not only developing the skills required by the curriculum, but also developing presentation technique and confidence.

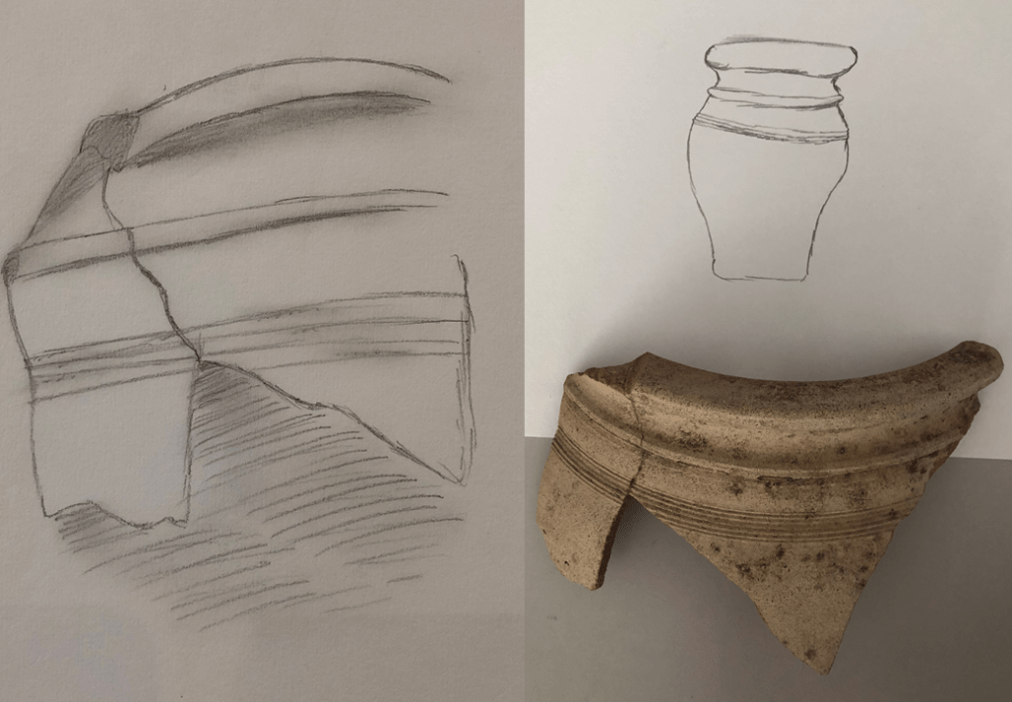

In our exploration of the types of objects which are found on archaeological sites students come to recognise that broken pots are the most common items turned up at excavations. Our second hands-on activity is a pottery analysis exercise which allows the students to handle ‘real’ objects. Our students are genuinely thrilled to be holding an authentic object. When they learn of their tomb context, they become even more intrigued. These objects thus make ideal tools for awakening intellectual curiosity. Fragmentary objects such as these are held in many collections but often relegated to storage as they are difficult to curate effectively. In our project, we wanted to put them to new use, bringing them out into rural classrooms and putting them in students’ hands.

The sherds we work with belong to the University of Melbourne teaching collection, obtained as a result of a series of Australian-Syrian excavations undertaken in the 1980s. The students gear up with gloves and magnifying glasses in hand, and are each given a single diagnostic sherd to examine. Following close observation and consideration of their object they are given the opportunity to either draw or write about the sherd, and consider the shape, size, appearance and purpose of the pot before it was broken. The option to express themselves visually or textually ensures everyone is given the maximum opportunity to communicate the results of their work. Again, students are given the chance to share their discoveries with the class. How was this pot made? What was the pot used for? What was its significance to the people of the past?

Project learning and teaching materials also include a range of ancient Egyptian replica objects, many of which represent gods and goddesses. To introduce the objects we play a card matching game; students break into pairs and race to match images of gods and goddesses with their brief textual descriptions. Upon completion of the game each pair is assigned a replica of a specific god/goddess, for more detailed exploration, followed by another knowledge sharing session. This leads into our final observation activity, in which the students examine a large image of the vignette of Spell 125 from the Book of the Dead, identifying the gods and goddesses they have learned about in the card game and the object handling exercise. This is a multi-layered activity which continually reinforces the students’ knowledge base.

Other activities focus on multi-sensory learning strategies. A 2015 study considering the value of ‘learning objects’ as a means of developing the literacy skills of Special Educational Needs children employed a method labelled ‘discriminative-perceptual learning’ – teaching a child to perceive sounds and relate them to objects (Jadán-Guerrero and Guerrero 2015). At a basic level this approach is used in the simple games we play with very small children, when we show them a picture of a dog and make a woofing sound, or moo while pointing out a cow. For our project, we wanted to harness the power of a multi-sensory approach by adding an audio element to reinforce the visual information conveyed by an object. The use of sound recordings rather than texts, especially when linked to tangible objects, can help to elucidate concepts which students who deal with low literacy challenges often find difficult to understand.

To test the efficacy of a multi-sensory strategy we developed our ‘Tomb in a Box’. The box is decorated on the outside with images of the cliffs in the Valley of the Kings, and on the inside with typical tomb wall paintings. The objects in the box carry a sticker on their base which is embedded with a voice file; when the object is placed on the box ‘brain’, a concealed speaker, it ‘talks’. The box contains a 3D printed pot and sarcophagus, a full set of stone miniature canopic jars, replicas of figurines of Osiris, Anubis, Ma’at and Horus, a shabti (a funerary figurine), and the Book of the Dead Spell 125 vignette, the Judgment Scene, printed on papyrus.

The collection of objects is introduced by a postcard written home to Melbourne from Egypt by the archaeologist Edward Miller in the early twentieth century, telling of his adventures in Egypt and of the objects offered for donation by the expedition’s leader Professor Flinders Petrie to the Egyptology collection in Melbourne. (Edward Miller’s brother Everard, to whom the postcard is addressed, was recognised for his philanthropy, including to the University of Melbourne.) A group of multi-layered questions requiring both object observations and attention to audio information has been formulated for each object. Each student is given the opportunity to remove an object from the box and place it on the speaker. The students listen to the story told by the object and then respond in writing on their worksheets. We lead discussion about the objects in order to build on the information learned in our hands-on activities.

Years 7, 8 and 9 students have been exposed to the Tomb in a Box. At Year 7 level it worked better as a tool employed in a directed teaching model as some of the group found observing, listening and composing a written response to questions, quite challenging. At Year 9 level however, the potential for self-directed learning was evidenced. Students were able to work more collaboratively, and they demonstrated an ability to listen, read, comprehend, and write within a confined timeframe.

Following our school incursions students are offered the opportunity to spend a full day in Melbourne, on the university campus. The morning of their visit is spent in the Arts West object labs – an extraordinary learning and teaching environment. The session in the labs is intended to expand on our work done in the schools, but on this occasion, instead of replicas, the students are exposed to authentic objects. Working in the labs, surrounded by ancient relics, is a uniquely inspiring learning and teaching experience. We find it immensely rewarding to share these resources, even if on a small scale and only briefly, with a cohort of students who are often far removed from the privilege that smooths the way to pursuing a university degree.

In the labs we further our exploration of the processes of mummification. Students are familiar with canopic jars from the replica set in the Tomb in a Box but in the labs they are able to see a pair of authentic New Kingdom limestone canopic jar lids. We remove these from the display cases to facilitate a powerful personal experience. A 3D print of a full size canopic jar, which was commissioned by the project, is employed to assist in understanding the scale of a jar in its entirety. The print and the authentic lids bring to life and amplify the detail students have learned in their classroom.

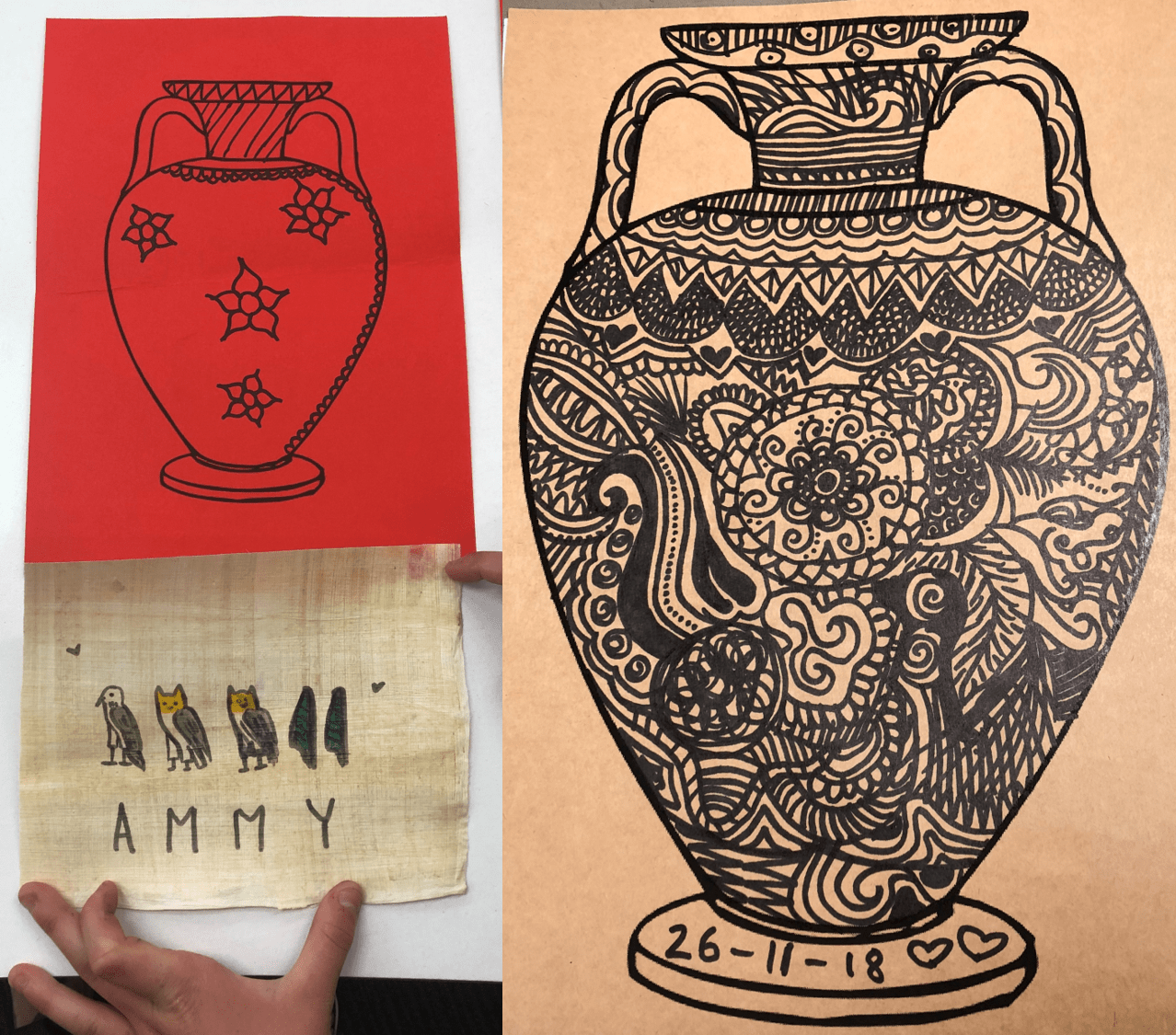

In the afternoon students participate in a range of hands-on creative activities. At Year 7 level options include decorating a template of a Greek vase or a miniature ancient Egyptian coffin lid, creating a scene from the Book of the Dead, writing in hieroglyphs on authentic Egyptian papyrus, painting a mummy mask, or playing the role of a journalist and interviewing someone from the ancient world. Year 8 students visit the Virtual Reality studio in the Medical Building, where they experience the beautifully decorated New Kingdom tomb of Nefertari. During the afternoon session they are given the opportunity to become practising field archaeologists, in an extension of the incursion pot sherd activity. Simulated archaeological sites which are rich with objects are explored; shells are sifted from sand and objects are sorted. Students then collaborate with their classmates on other sites to share finds and ensure each group has all of the objects to enable reconstruction of a decorated plaster stela or a broken pot.

We were keen to discover from our students what stories they would like to tell through their own objects, and so in an inter-school collaboration our Year 9s developed their own ‘Goulburn Valley in a Box’. The box features two icons of the regional dairy industry: Bessie the Friesian milking cow, and a decorated cow, which is emblematic of the outdoor Moooving art project for which the district has become famous. It also incorporates a John Deere tractor; an AFL football; a snake which was responsible for creating the great Murray river as told in a Yorta Yorta creation story; a Southern 80 speedboat which is central to a famous water ski race held annually along the Murray river; a platypus; and a long-necked turtle, which is a Yorta Yorta totem. These objects are housed in a small, portable case which is decorated on the outside with imagery of the Goulburn Valley landscape, and on the inside with Australian wildlife. As with the Tomb in a Box, each of the objects will carry a voice file describing its significance to the Goulburn Valley. The voice files will be made available in multiple languages.

Who would be interested in our Goulburn Valley in a Box? As it turns out, everyone we have approached. The Goulburn Valley Project has developed into an international collaborative effort which now has branches stretching to Manchester in the UK, Cairo in Egypt and a small village on an island in the north of Sudan (details on this coming soon). We are currently working with colleagues from the University of Manchester in the development of a virtual ‘Manchester Museum in a Box’ and a range of teaching materials which will be shared with our Goulburn Valley students, thus adding another layer of learning to their study of the ancient world.

At the end of their day in Melbourne, prior to their departure back to the Valley, students complete a short survey about their experiences. What is especially notable is that following only brief exposure to the program, participants report not only an elevated interest in studying history, but an expansion in their knowledge base. A particularly gratifying aspect in delivery of this project is seeing students who are often challenged by text-based learning because of their low literacy skills, excited by their visual and tactile discoveries.

There are still many challenges to be addressed as our students move on to senior secondary levels. The shortage of teachers qualified to teach ancient history means that rural schools are often unable to cater to students’ preferred subject choices. Sometimes schools offer subjects by correspondence instead, but this is not ideal. Our project has shown that if students are actively involved in a learning experience because it is what they choose to do, that ability to make a choice is reflected in their levels of interest and engagement, and therefore in their learning outcomes. Highlighting these findings may help incentivise schools to hire teachers who can offer these subjects.

We have proven that even mundane objects such as lids, buttons, and shells are able to contribute to a climate of educational equity. After four years of working with our students in the Goulburn Valley, and by adopting a multi-sensory hands-on humanities methodology we have witnessed enhanced knowledge transfer and information retention. This approach to learning and teaching has particular application for students with additional educational needs. The reactions of students, teachers and international colleagues to our project confirms the thirst that exists for alternative classroom approaches. Following our four years of successful project delivery, and outcomes measured by simple surveys and our own observations, we are now expanding our research focus to explore the ability of artefacts to mediate diverse experiences and therefore promote empathy. We are confident our work will produce outputs which are both transferable and scaleable. If you would like to learn more about our work, I would be delighted to hear from you, via email.

Acknowledgements

Associate Professor Andrew Jamieson was my collaborator at the founding of this project and continues to provide support. I would especially like to acknowledge Dr Annelies Van De Ven who shares my passion for our program and vision for its future. Annelies completed her PhD at the University of Melbourne in 2018 and in the second year of project delivery accompanied me on the school incursions. Although Annelies is currently working on her research fellowship in Belgium, she returns to Australia each year to join me on our visits to the Valley and we will be spending time together in Manchester this year. Projects such as these do not occur without funding, and we are particularly appreciative of the support offered by the Melbourne Engagement Grants program, the University of Melbourne Equity Innovation Grants program, and SHAPS.