Rebuilding Life after Mass Violence: Lessons from the Chilean Truth Commission

History PhD candidate Amy Hodgson was recently awarded a prestigious Yale Fox International Fellowship. This graduate exchange scheme supports students who are committed to harnessing scholarly knowledge to respond to urgent global challenges. The Fellowship will support Amy’s research into the history of Chile’s post-dictatorship truth commissions. For her project, Amy has carried out a series of oral history interviews both with victim communities and with members of truth commission staff. Read more about her work below.

Could you tell us a bit about your PhD project?

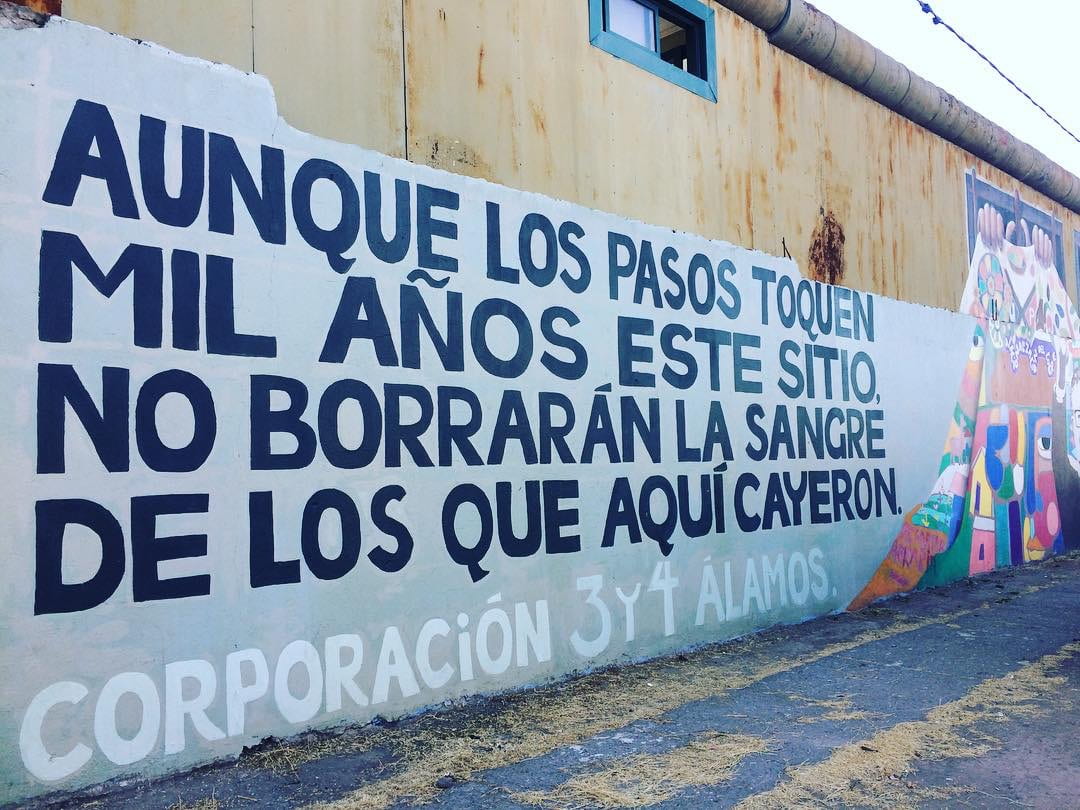

My research looks at attempts at national reckoning and reconciliation in Chile, after the mass human rights violations that occurred under the Pinochet dictatorship (1973–1990). Huge numbers of people were imprisoned, tortured, ‘disappeared’ and assassinated for political reasons, and the Pinochet government denied and concealed state violence during their rule.

After the dictatorship fell, the succeeding governments created two truth commissions in an effort to acknowledge and come to terms with the violence during the Pinochet period: the 1990–1991 National Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Comisión Nacional de Verdad y Reconciliación) and the 2003–2004 National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture (Comisión Nacional Sobre Prisión Política y Tortura). I’m interested in uncovering how these truth commissions were experienced by victim communities and truth commission staff.

I found that a lot of the research surrounding truth commissions focuses on how the national community received the final report. I felt like more needed to be done on the operational periods of truth commissions – the actual work! I wanted to look at individual experiences, especially those of testifiers. What were testifiers’ reactions to the announcements of the truth commissions? How did they feel they were treated during their interviews?

Oral history allows me to ask testifiers these questions and provide small windows into the emotional impact of truth commissions – both beautiful and difficult moments. For example, when someone is recounting events that violated their sense of dignity, safety, and humanity – as the acts collectively referred to as ‘human rights abuses’ do – something as subtle as the tone of the interviewer’s voice can be a source of comfort, or it could be traumatic for the testifier. When we pay attention and listen in-depth to testifiers’ experiences, we can discover things that may help to improve the processes for future endeavours of this kind.

What first sparked your interest in truth commissions and Chilean history?

I think my interest in history and truth commissions both revolve around a love for narrative. My history education began with my grandparents’ life stories. These stories were often about their personal experiences of war and migration and the complex task of rebuilding after a rupture. My grandfather arrived in Chile in the 1950s as a Polish refugee from World War II. He met my grandmother in Chile and in the 1970s, with their children, they migrated from Chile to Australia. These events forced them to rebuild themselves as individuals and their families, uprooted from their networks and in a new land. For them, rebuilding was filled with possibility and hope, but it was also isolating, even traumatic. As a child listening to these stories, I was perplexed at how such conflicting emotions could sit side by side, and the way that rebuilding after trauma was also traumatic.

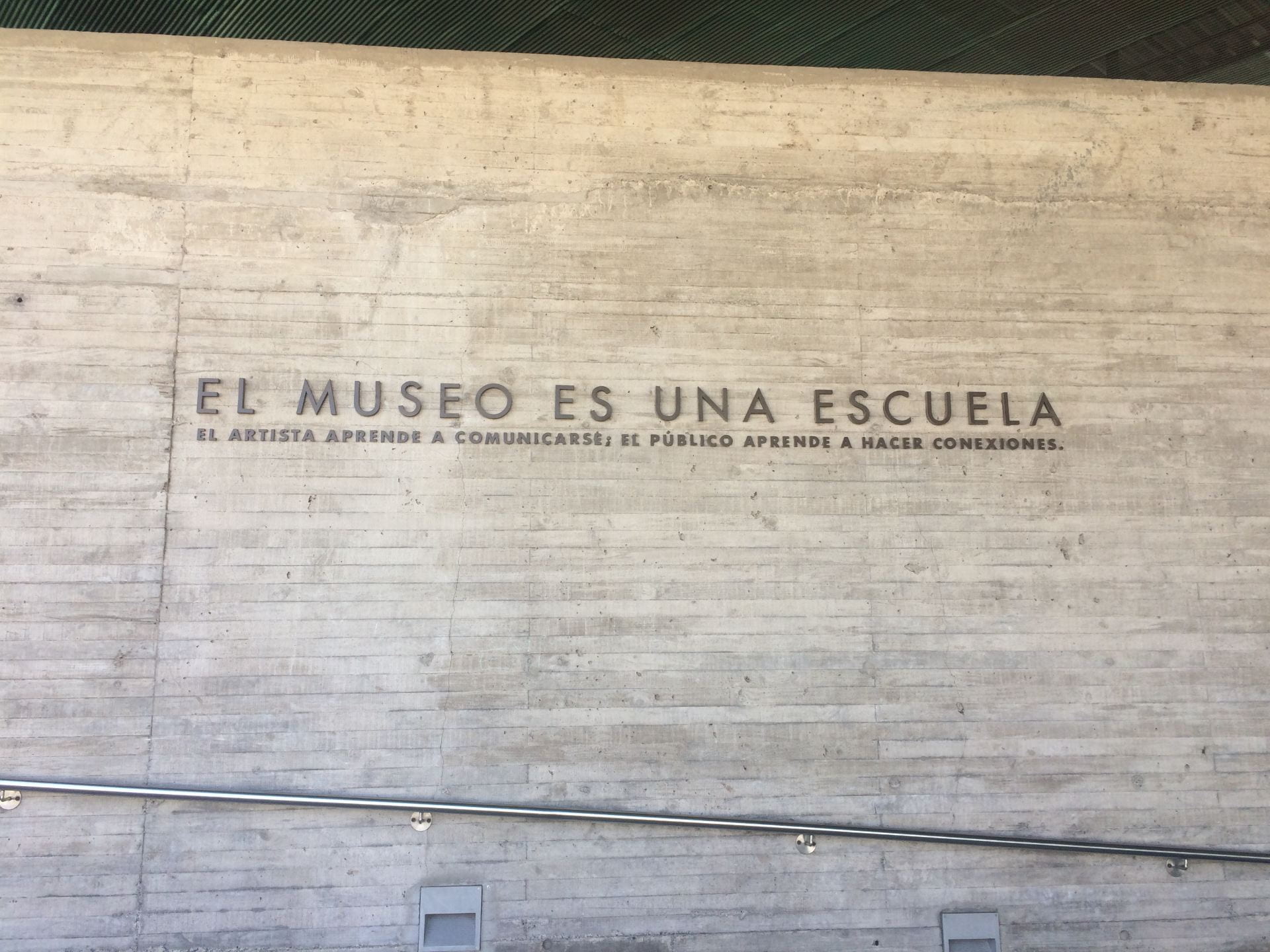

Truth commissions are a state-sanctioned attempt to [re]build through narrative after a recent period of mass violence. They are created by the state to investigate and establish a clear account of what happened to whom and why and provide an understanding of the experiences of victim communities. Truth commissions are also a reparative gesture to those victim communities and an attempt to [re]set the values of a society after mass violence, increasing respect for human rights.

What I find interesting about truth commissions is the moral, political and emotional complexities of state-sanctioned [re]construction. On the one hand, there are those who must revisit their suffering in their testimonies to have their experiences acknowledged and contribute to the historical record. On the other, there are those who are charged with receiving and making sense of these devastating individual histories while balancing the politics and expectations of the wider community. There is inevitably a level of compromise within truth commissions, and it is important to know and acknowledge the emotional impact of these compromises for the individuals involved, especially within victim communities.

What are some of your favourite things about your research?

Interviewing is the most valuable and most difficult thing about my research. It is rare in history that we can speak to the people we study, and I am privileged that many of the main actors in my research are still around and generous enough to share their time, memories and knowledge with me. They’ve let me into their homes and workplaces, and there is something special about interviewing someone who has survived human rights violations in a room filled with pictures of their grandchildren – an individual’s strength and resilience really becomes apparent in these spaces. Interviewing also enables me to capture moments, memories and emotions that aren’t accessible anywhere else.

Interviewing can be really rewarding, but it’s also really hard. It’s a complex task and I’m always exhausted by the end of an interview, no matter how lighthearted it may have been. I learnt to speak Spanish at home with family, so I’m always self-conscious – I cannot tell you how often I’ve anguished about accidentally using the informal tú instead of the formal usted in an interview. I really admire truth commission interviewers – it’s a difficult task that comes with a huge burden of responsibility.

Can you tell our readers about your most memorable fieldwork experience?

One of my most memorable fieldwork experiences was during an interview with an ex-prisoner. This person let me into their home and their dogs were running about, excited for a visitor. While we were doing our interview one of the dogs lay on the floor between us, keeping us company. The interviewee wanted to speak about some of the abuses they suffered during the dictatorship and the various ways they had revisited these experiences in the decades since Chile’s transition to democracy – truth commissions, court testimonies, returning to places of detention. These were emotional memories and the interviewee paused a few times to pat their eyes with a tissue.

Suddenly, there was this soft gurgling sound and we both paused trying to locate where it was coming from. The dog on the floor was snoring, and we burst out laughing. The dog’s snores had ripped us both out of this vulnerable moment and we were disoriented afterwards, but in a good way. It’s not a moment of great insight or anything, but it was a moment that made me think, I love oral history. The interviewee was someone I deeply admired, so it also stands out as this special, funny, human moment I shared with one of my idols!

What does winning the Fox Fellowship mean for you?

The Fox Fellowship represents an incredible opportunity to further develop my research project and, hopefully, increase any potential impact on the transitional justice field. Yale University has a long and distinguished association with transitional justice and human rights research and being on campus will give me an opportunity to explore past and present projects. I’m excited to be close to the Schell Center for International Human Rights at Yale Law School, which has produced some great research on transitional justice and even a few alumni with enviable careers in the field.

The coronavirus pandemic has seen me glued to the news these past few months, of course, and I’m weighing up the risks of travel at this time. I’ve still got a few months before the fellowship begins and, for now, I see some light at the end of the tunnel. Either way, it’s an absolute honour to be awarded the fellowship.

The Artemis Project Student Initiative is also something I’d like to investigate. The project was an attempt to unite the archives of truth commissions around the world in a single place, representing a big collaborative moment. Recently, I stumbled upon the project and a connected 2006 conference at Yale University, and I was immediately intrigued. I’m desperate to find out more about it, and I’m hoping I’ll be able to do that when I’m there.

Above all, the Fox Fellowship represents an opportunity to communicate my research to and collaborate with people I never would have connected with otherwise. I’m eager to meet the other Fox Fellows from around the world, all working to improve possibilities for peace. I have no doubt there will be intersections between our projects that we could learn from.