Applied Proof Theory: Holding an International Workshop during the Pandemic

How do you hold an international workshop at a time when travel between continents is at a standstill and countries all over the world are in lockdown? Greg Restall, Professor in Philosophy, explains how this worked at the recent international workshop on Applied Proof Theory.

The academic calendar used to be punctuated by large conferences and smaller workshops, where researchers from all over the world would come together, present papers, discuss their work, catch up with old colleagues or meet new friends. All of that came to a standstill in 2020.

Nevertheless, we have been finding ways to make do with the resources we have at hand. This year, everyone has become acquainted with online tools such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams and Slack. Many of us have used tools like this to keep in touch with our students while we attempt to teach from our home offices and, so, it’s not much of a stretch to run research workshops using the same tools. So that’s what the Logic group at the University of Melbourne did for two days in November. To mark the end of the Australian Research Council funded project, Meaning in Action, the postdoctoral research fellow Dr. Shawn Standefer and I hosted an international workshop bringing together colleagues from all over the world to talk about proof theory and its applications.

What this is about

Philosophy has always interested itself in logic. When you’re thinking about fundamental questions on which reasonable people disagree, it’s natural to step back and wonder what the rules of the game are – or what they should be. Almost as soon as we started arguing with each other about right and wrong, about what the world was really like, or about how we should live together, we also started thinking about how those arguments should go. The very question of what makes good reasoning good is a perennial question in philosophy, wherever it is found.

Logic has developed in many different ways throughout the centuries, from the syllogisms of Aristotle, developments in the Arabic world by Ibn Sînâ (Avicenna, d. 1037), treatments of supposition and consequence developed in the late middle ages by Buridan (c1300–1361) and others.

From the nineteenth century, work in logic exploded in detail and complexity, as mathematicians attempted to come to grips with the kind of reasoning involved in making proofs in the infinitesimal calculus. Mathematicians were making wilder and stranger claims, about infinitely small quantities or infinite collections and, in so doing, they were flirting with paradox and inconsistency. Mathematicians and philosophers found that the tradition stemming from Aristotle gave little to no guidance as to when this reasoning was correct and when it was overreaching. Philosophers needed to develop new tools to understand and evaluate reasoning with far greater depth and complexity than ever before. This is the soil out of which modern logic flowered from the late nineteenth century and it was from this time that the two traditions of model theory and proof theory took form.

In model theory, the focus is giving shape to understanding how different claims about things could all be true together. Models don’t have to represent how reality actually is, but they represent how things could be. The better we are at building and understanding models, the better we are at understanding the things that these models can represent. In particular, we can show that a piece of reasoning from some premises to a conclusion leaves out a crucial step if we can build a model according to which all the premises are true and the conclusion is not true. This model doesn’t tell us that the conclusion is false, but it does tell us that the conclusion doesn’t follow from those premises alone. If we want to know why the conclusion is actually true, we need to spell out our reasoning some more, to fill in those missing assumptions, to explain why that model should be ruled out.

Proof theory looks at things in reverse: instead of focusing on models as ways to block bad reasoning, we focus on what makes good reasoning good. A proof theorist attempts to give an account of the different principles of good reasoning, to explain how to build proofs which leave nothing out, to understand what we can do with them – and for philosophers, to attempt to get to grips with how these principles connect to how we can grasp concepts, how we can learn things, how we can come to agree with or disagree with each other, and so on.

These connections between proof theory and other areas in philosophy and beyond philosophy were the topics of our workshop, held from 5–6 November 2020.

Who we invited

The workshop included eight talks, from a range of early to mid-career researchers from around the world. There were four presenters based in Australia (Shawn and me, Dave Ripley [Monash] and Rajeev Goré [ANU]), one from the US (Teresa Kouri Kissel, from Old Dominion University in Virginia), one from Argentina (Natalia Buacar, from the University of Buenos Aires) and two from Europe, (Rosalie Iemhoff from the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands) and Andrew Arana from the Université de Lorraine, in France).

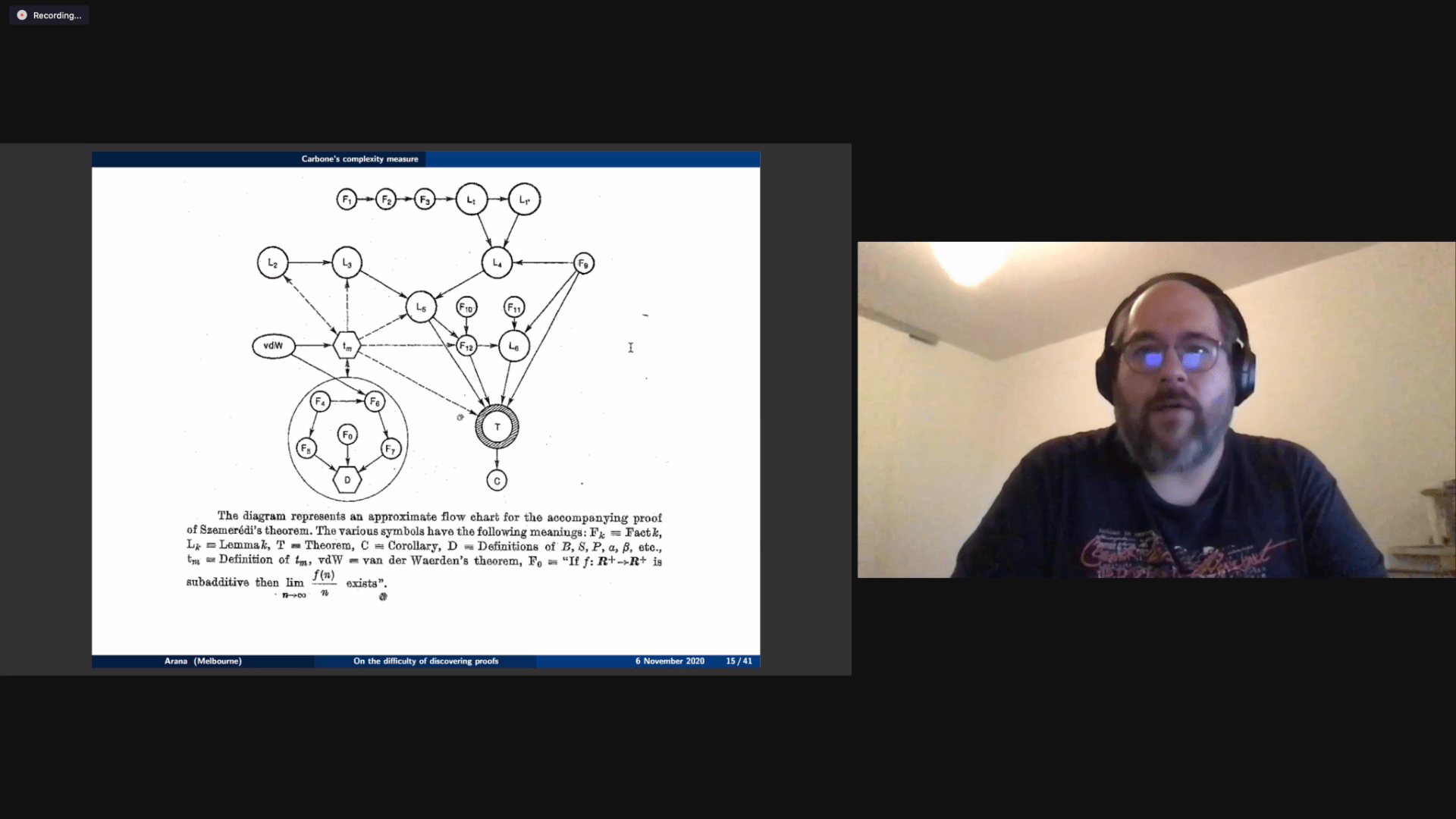

The talks covered a range of different topics involving proofs and how they can be applied and understood. For example, Andy Arana talked about different ways to understand the complexity of proofs and attempts to understand the distinct ways that certain kinds of proofs might be difficult to discover but once discovered are more straightforward to understand.

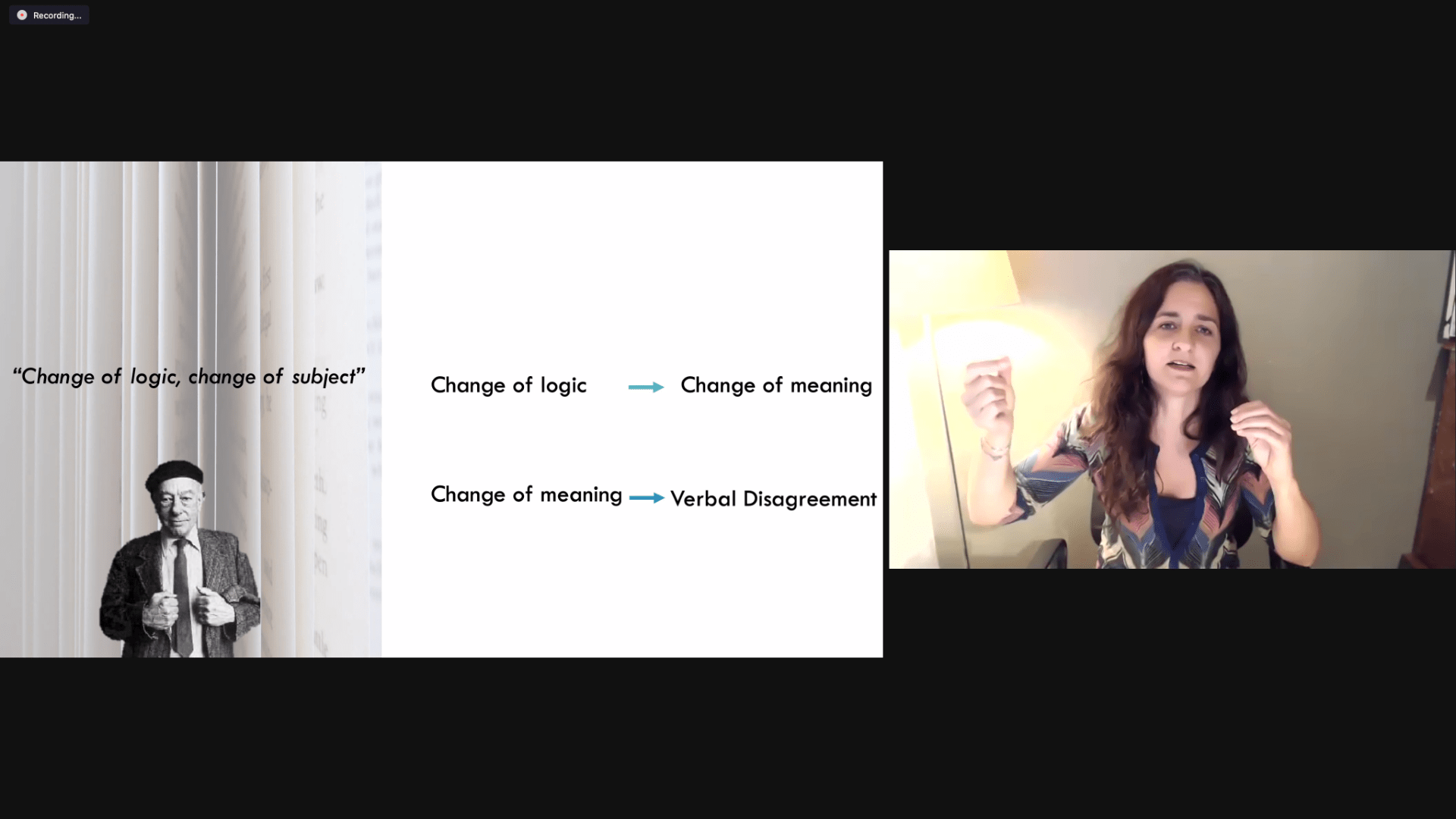

Natalia Buacar presented on the way that logic and proof provides a perspective where we can not only analyse disagreement, but also locate different kinds of ways that those coming from different perspectives turn out to agree.

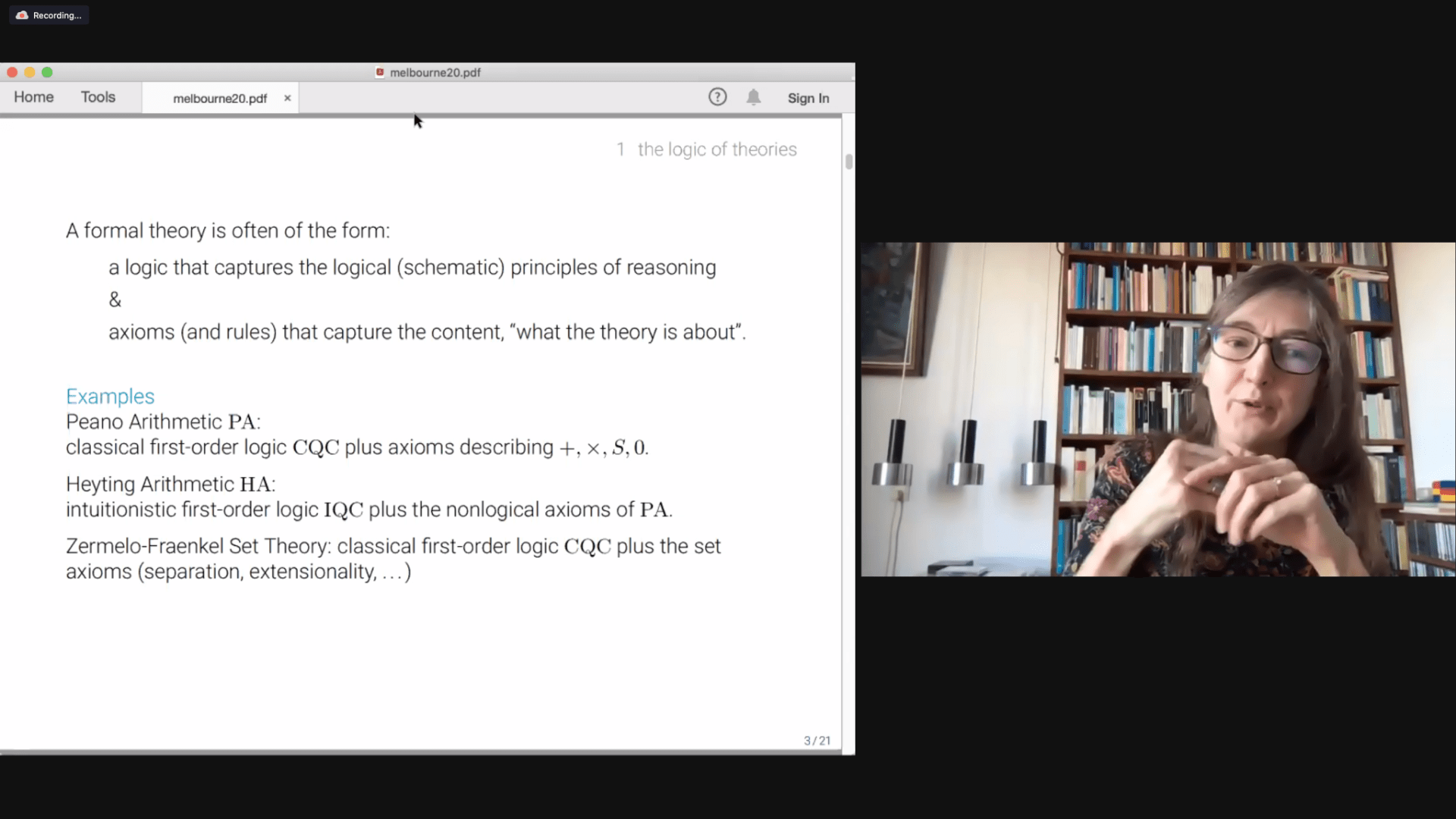

Rosalie Iemhoff gave a detailed presentation on how we are developing techniques for understanding the ways that different logical principles can be extracted from individual theories that are formulated without using those principles in the first place.

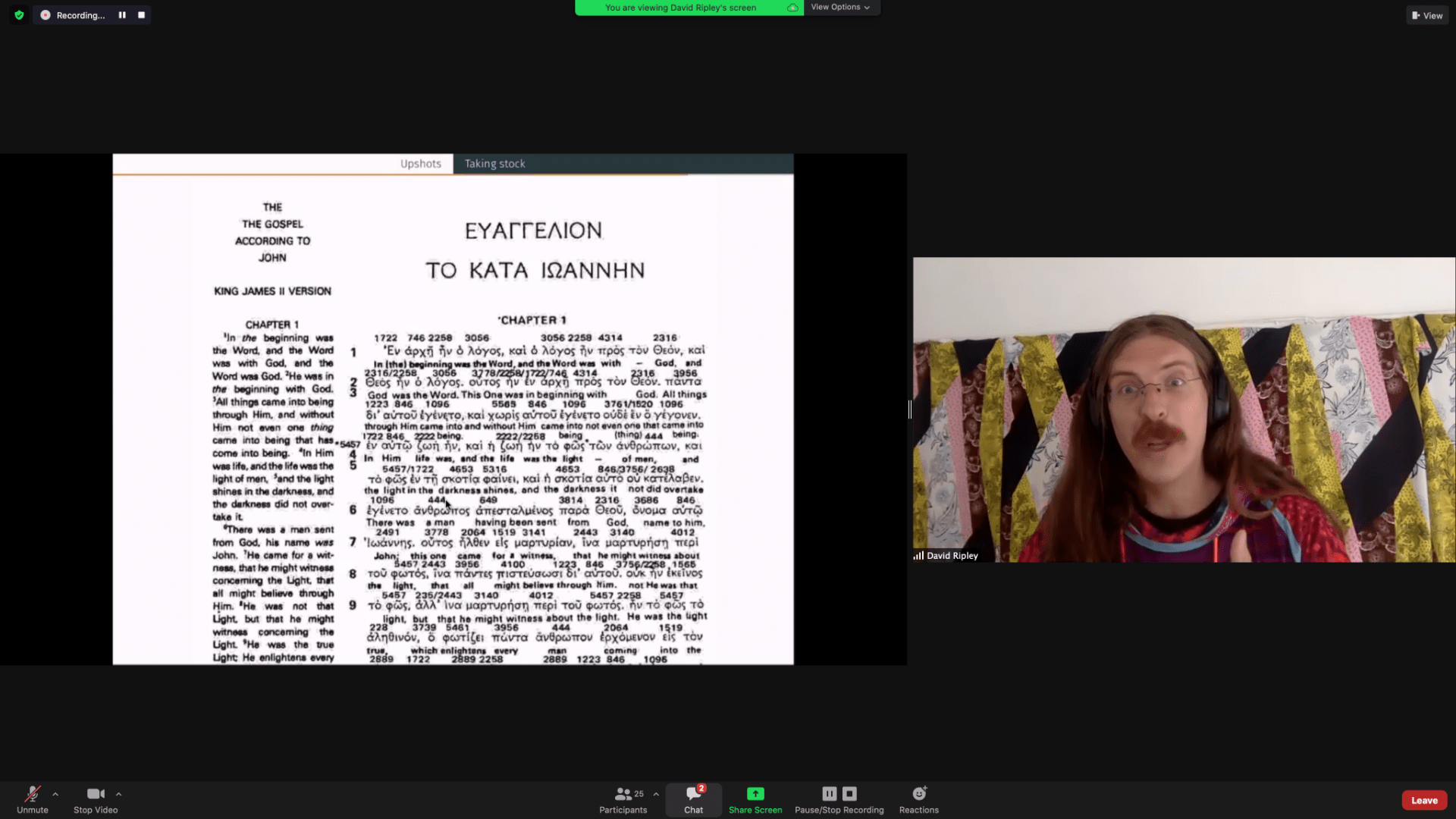

Dave Ripley explored the parallels and differences between the ways that proof rules can be used to define concepts, as explored by proof theorists, and the ways that computer scientists understand rules governing different data types in functional programming languages.

The talks ranged widely, drawing connections to philosophy, computer science, mathematics, and other topics.

What we learned

With four talks each day, we had participants from all over the world, some waking up very early or staying up very late to participate live in talks that were streamed over Zoom. Each talk was followed by at least 30 minutes of live Q&A with the audience. This resulted in good interactions and connections to be drawn between talks and across different research communities. Presenting talks over Zoom and from our own homes means that we had less opportunity to have those serendipitous conversations over coffee or dinner, but we kept the Zoom room open between talks for people to hang around and catch up or make new friends as they were available.

We recorded each talk and made the recordings available to workshop participants, so those in adverse time zones could watch what they missed. We used Slack, a freely available online discussion platform, to facilitate ongoing Q&A and discussion for each talk, for participants who are able to do this live, and for those who could only watch the recordings.

Presenting online means that it is much more straightforward to record presentations than it is for a face-to-face workshop, since there is no need to set up cameras to capture a talk – as we are all doing that ourselves, anyway. In addition, it was so much cheaper to run, and we had much less impact on the environment, since we did not need to fly participants from one side of the world to another. We could get a diverse set of speakers, subject only to their availability at the time, without committing them to any more than the days of the workshop itself, together with some occasional participation in the online Slack forums. They do not need to commit to days of international travel and the disruption this involves. There are many up sides – as well as some down sides – to conducting research meetings online in the time of a pandemic.

For more details about our workshop, including abstracts of all the talks, visit the workshop website.

Thanks to the Australian Research Council, grant DP150103801, for support which made this workshop possible.