Happy Ancient Roman Mother’s Day

SHAPS Honorary Tamara Lewit explores the celebration of Mother’s Day in ancient Rome, in this article, republished from Pursuit.

Although the words ‘ancient Rome’ might evoke marching armies or gladiatorial combats, those armies and gladiators would never have existed without their mothers.

Like us, the Romans celebrated a Mother’s Day. But never mind breakfast in bed and a bouquet, on Roman Mother’s Day, women served their own slaves and offered up flowers to a goddess.

Only scraps are known about this celebration, and modern historians have seldom given it much attention. The festival was held on 1 March, the start of Spring and the first day of the year in the archaic calendar.

The Roman poet Ovid describes a “crowd of mothers” thronging the temple of Juno Lucina, goddess of childbirth. Married women wore wreaths and made offerings of flowers, pregnant women wore their hair loose and prayed for a good birth.

Husbands offered incense in prayers for the continuation of their marriage.

The main event of the festival was a reversal of normal roles, in which women served a holiday feast to their household slaves instead of being waited on themselves. But husbands did give their wives presents – although gifts between husband and wife were normally forbidden by law.

Men also gave presents to female friends and girlfriends, so that “numerous traveling gifts roam everywhere … in a procession through the city’s streets and houses”, as another poet wrote.

In the third century CE, the Christian leader Tertullian grouched about the present giving and noisy feasting of Christians who still celebrated the Pagan festival, which endured over a period of nearly 1000 years.

I found out about Roman Mother’s Day while exploring the roles of Roman mothers in my research for a children’s historical novel A Message Through Time, written by my sister, Anna Ciddor, and recently launched by Associate Professor Gijs Tol.

In the novel, an ancient Roman girl accidentally travels to the present and makes a difficult and dangerous journey to be reunited with her mother in the fourth century CE.

We wanted to tell the stories of Roman girls – their everyday lives, relationships and experiences – to modern children aged eight to 13.

Since Roman writings tell us so little about girls of this age, and motherhood has not been a popular topic among historians, my research was a jigsaw puzzle put together from fragments of modern historical analysis, ancient letters and poems, grave finds, inscriptions and images.

Our protagonist Petronia’s primary relationship is not with her mother, but with her slave carer.

Roman babies were breastfed by slave women, even within the lower ranks of society. The slave wetnurse and nursemaid (called a nutrix) is frequently referred to in Roman inscriptions, literature and letters.

A nutrix was a mother figure – her name or image often appears on children’s funerary monuments alongside those of the child’s biological parents. Inscriptions sometimes refer to her as “mamma” or “mammula” – a term like “mummy” – as well as nutrix.

Nursemaids seem to have had a lifelong relationship with their nurselings and appear as companions to adult married or widowed women in literature (even occasionally assisting in sexual assignations).

Roman law made special provisions for freeing a nursemaid and her children on the basis of special affection.

It was the nursemaid who bathed the baby, cared for the sick child, and sang the lullabies. “She’s the one who gives me hugs, and calls me her little chick, and sleeps in my room”, explains Petronia in the novel.

In contrast, Petronia’s mother is remote, and rebukes her for unseemly grieving over her pet dog’s death.

The ideal Roman mother was stern rather than affectionate. Little distinction was made between male and female parents in this respect. Sons and daughters owed both their parents filial duty and obedience.

Although women were honoured for bearing children, a mother’s primary duty was not to nurture her baby but to see her adult daughter suitably married. Mothers as well as fathers – although not the young girl herself – were involved in the choice of their daughter’s husband.

Even though men negotiated marriages, mothers also found, approved or vetoed marriage partners. The betrothal of Tullia, daughter of first-century BCE politician and writer Cicero, was arranged by her mother in his absence.

Tullia was betrothed at thirteen and married when she turned fifteen or sixteen.

Although Roman law set the minimum age for girls’ betrothal at seven and marriage at twelve, customs may have varied in different regions of the Empire and for different ranks.

In southern Gaul, for example, most graves of young girls were dedicated by their parents – indicating that they were unmarried – until they were in their late teens or early twenties. Girls were usually married to men around ten years older, but sometimes the age gap was wider, with young women marrying men of their father’s generation.

Many indigenous religious practices continued in the provinces of the Roman Empire, and Celtic mother goddesses called the ‘Mothers’ (Matres) are mentioned in inscriptions and represented in sculptures from Spain to the Rhineland.

They are usually shown in groups of three, holding or breastfeeding swaddled babies, with a wool-making distaff or with symbols of abundance like a basket of fruit.

They were also healing goddesses, often worshipped at natural springs, where people came with sculpted offerings of arms, legs, whole bodies, eyes, heads or swaddled babies.

So perhaps this Mother’s Day, we should think not only of our own mothers, but of those mothers and mother figures throughout history who nurtured, nursed and guided children.

The children’s novel A Message Through Time by Anna Ciddor, based on Tamara’s research, is available now.

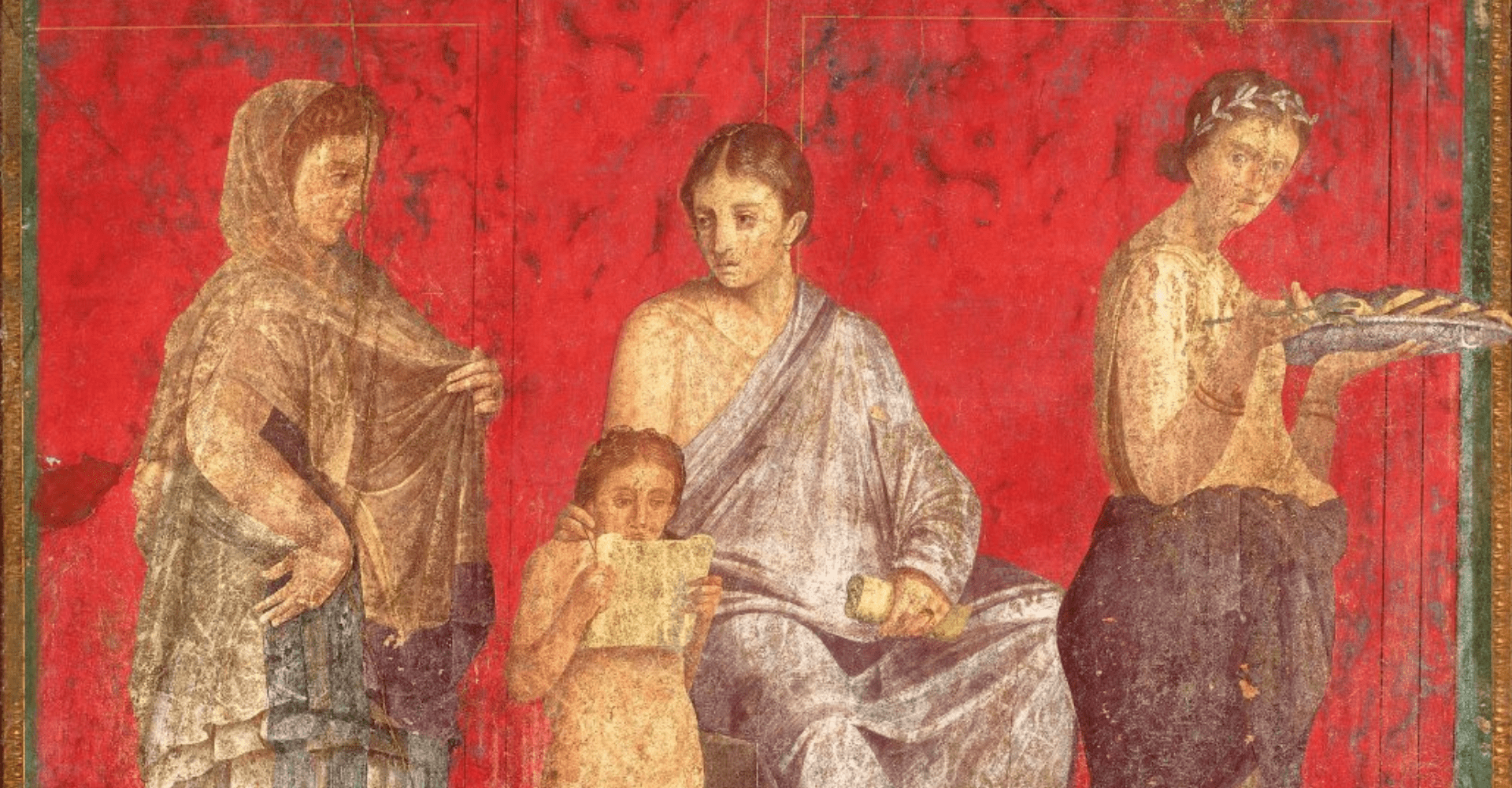

Feature image: Detail of Roman wall painting from the Villa of the Mysteries, Pompeii, c60CE via Wikimedia Commons