What Remains of a Performance When the Curtain Goes Down?

Archives are an incomplete but important record of dance and theatre, and the history and artistry of University of Melbourne students is being revisited through these ‘remains’. Arabella Frahn-Starkie, student in the Masters of Cultural Conservation, explores these questions in this new article, republished from Pursuit.

My journey to working with archives has been an unusual one. I followed my nose, pursuing interests as they unfolded in front of me, being intuitive rather than methodical. In this way archiving and curation came to me rather than the other way around.

I initially completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts (Contemporary Dance) at the Victorian College of the Arts and worked as a freelance performer for several years. I have always had a penchant for film and photography as a way to fuel my nostalgic tendencies and to frame and capture moments in time.

As a dancer working with the transient body and the temporary nature of the art form, getting close to the traces left by dance, like photographs, videos or studio notes is a point of curiosity for me and feels important.

It wasn’t until the depths of the COVID-19 pandemic that I began to seriously think about the ‘remains’ of performance. It was a combination of the compulsion to hold on to my community, the loss of live performance that would normally surround me and a moment in time where I had the space to think – what are the broader repercussions for this art form if it is not adequately or appropriately remembered in its historical context?

A filing cabinet or a digital hard drive as a resting place for a dance is like a ten-year-old’s set of teeth – there’s something always missing.

After studying for my Honours in dance in 2021, I decided to broaden my interests in this rather niche area. So, I began a Master of Cultural Materials Conservation at the University of Melbourne, with a focus on intangible cultural heritage.

This has grown my understanding of the cultural impact and ethics behind conservation and archiving work and given me great insights into the preservation of the material traces of performance – like video and photography, both in analogue and digital forms.

The history of performance remains most strongly in the bodies that perform and experience it. There is a growing awareness within dance academia that it is impossible to authentically archive and reproduce performance through media alone.

This means we need to adapt archival processes to better understand the knowledge systems within dance that are not written or easily reproducible through object-based or digital mediums.

The absence of the moving body in performance archives points to the friction between the form and our record of it. This point of friction inspired me to shift my creative practice to working with dance traces to produce performance work.

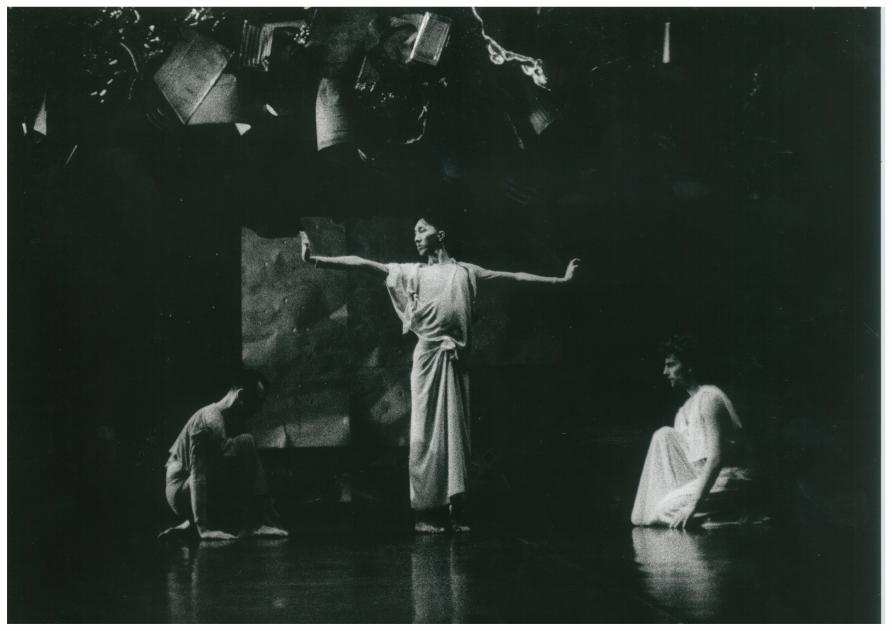

My curation of the film festival Live Remains shows this creative practice at play. For example, I created an interactive photographic installation that is viewable across both days of the festival in the Guild Theatre. By printing photographs of Union House Theatre plays from the early 90s onto transparency film, audiences can sift through the theatre’s history as though they are rummaging around their own family photo album.

As a student archivist intern at the University of Melbourne Student Union (UMSU), a position open to students doing graduate study at the University, I became well acquainted with the performance histories of students, particularly through their engagement with Union House Theatre and its long and rich legacy of performance making on campus.

This gave me a unique opportunity to activate the archive to share the ephemeral past with current students and provided me with the chance to apply my study to practice; to enliven the archives, explore the rich history of art making on campus and its connection to politics and freedom of expression.

I like the concurrent eerie and playful meanings that arise from the festival title Live Remains. When I think about the term, several meanings come to mind: living, dying, enduring, something of the dead that is carried through the living, something of the living that is taken with death, leaving behind, looking back, the electrical pulse of video, capturing the three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional plane, something that is in the twilight zone, the living dead, remnants.

My key interest here is in live art forms, including theatre and dance, and what remains when they ‘disappear’? What endures and how? What can we learn or what can be productively gained through these traces?

In steps the moving image, and a premise for a film festival that brings to life the evidence of life, action, activism and art making of our students.

Live Remains is the inaugural UMSU film festival. This festival brings to light, and projects onto screen, the transient ephemeral cultural history and immense creative output of University of Melbourne students. It is curated by dance artist and researcher Arabella Frahn-Starkie, a VCA Dance (Hons) graduate and current MA Cultural Materials Conservation student.

Feature image: J Busby (detail), University of Melbourne Student Union Archives