Ancient Languages Boom!

Undergraduate enrolments in ancient languages are soaring at the University of Melbourne, with the number of students signing up for beginners’ level Ancient Greek, Ancient Egyptian, and Latin undergoing a dramatic rise in 2023 and 2024. Ancient World Studies PhD student Noah Wellington reflects on the reasons behind this.

Scholars have studied the ancient world for centuries and the literature and history of ancient Greece and Rome in particular has exerted a substantial influence over the western world. Yet, as Dr Tom H (for Hercules!) Davies noted in his inaugural lecture for the first-year subject Myth, Art, and Empire (ANCW10002), ‘Ancient World Studies’ as it exists today and is taught at the University of Melbourne is, in some ways, a very young discipline.

We are currently in the early stages of what promises to be a real sea-change in the field, as new visions of a more diverse and multilayered ancient world emerge. These are arising out of innovative scholarly approaches focused on the interactions between ancient cultures, and on bringing ancient literature and archaeological evidence into conversation with one another. Meanwhile, the influence of the anthropological turn of the last century has played a role in generating exciting new research into gender, race, class and disability.

Interest in the ancient world at the University of Melbourne is booming. Student enrolment trends are a vivid and welcome illustration of this. The freshly revamped first-year subject Myth, Art, and Empire (ANCW10002) saw record enrolments in 2023, with upwards of 300 students at its peak. Ancient languages are undergoing a huge upsurge.

Beginners’ Ancient Greek enrolments almost doubled from 2023 to 2024, reaching levels close to the consistently popular Latin 1 course, while beginners’ Ancient Egyptian enrolments also reached new heights, with enrolments doubling from 2023 to 2024. Students are also embarking on their own enrichment activities. Latin has also witnessed an almost doubling number of enrolments both in 2023 and 2024 (from an average of 40 to almost 70).

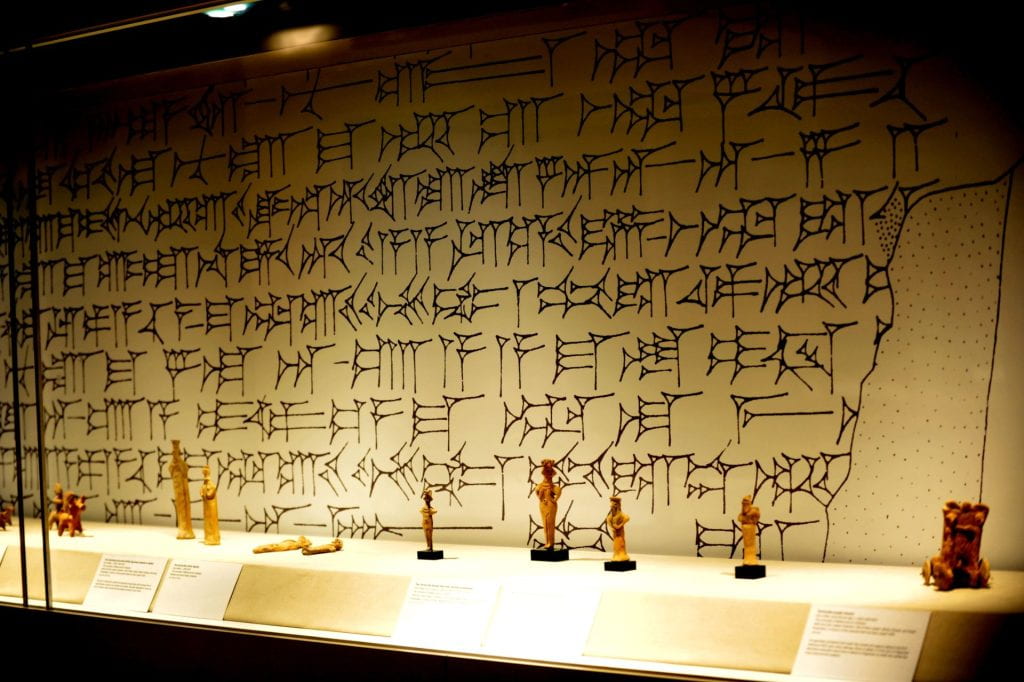

As of 2023 an especially enthusiastic group of undergraduates has been meeting on their own initiative to learn the Cuneiform script and Akkadian language, many of them inspired by the popular first-semester subject Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia (ANCW10001).

Fascination with the ancient world is nothing new. Adapting and updating ancient Greek and Roman myth and history to meet contemporary needs is an old phenomenon, a word we take from the Latin phaenomenon, itself taken from the ancient Greek φαινόμενον. (Dead language who?).

The world has not stopped handing down these stories since they were first told. In the western world schoolchildren in the medieval and Renaissance periods learned mathematics from Euclid and medicine from Galen; French revolutionaries looked to both Brutuses. Whether you’re reading Christine di Pizan’s The Book of the City of Ladies (1405), with its stories about famous women in antiquity, or admiring Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Socrates (1787), the ancient influence over art and literature is difficult to avoid.

The twentieth century was no different. Authors such as Mary Renault (The Last of the Wine, 1956; The King Must Die, 1958; The Persian Boy, 1972) and Robert Graves (I, Claudius, 1934; Claudius the God, 1935), as well as playwrights, choreographers and filmmakers drew heavily on the ancient tradition for inspiration.

The wide range of media listed in even this tiny sample – from Renaissance to Renault, from books to Broadway – remind us that the ancient world has always been popular and always relevant, albeit in different ways. Why and how we engage with the ancient world shifts constantly – from myth to history to philosophy to art to politics – there is something for every interest and every era.

Moviegoers watched sword-and-sandal dramas and Disney’s animated Hercules (1997), or adaptations of Oedipus Rex (1967) and Medea (1969) for the more tragic-minded; theatregoers saw the ballets Daphnis and Chloe (1912) and Apollon Musagete (1928), or Sondheim’s A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962), directly inspired by Roman comedies. And, when the century turned, who could forget Zack Snyder’s 300 (2006) or the infamous Troy (2004)?

So, interest in the ancient world has never quite died out – but how can we account for this current revival of interest, among university undergraduates?

Popular culture offers part of the answer to this question. Outside the classroom, a glance at the new fiction section in your bookstore of choice, on or offline, will show you that interest in the ancient (and especially the Graeco-Roman) world is booming.

You will find books about Cassandra, Clytemnestra, Ariadna, Atalanta, Electra and Galatea, all published within the last few years under eponymous titles. They’ll be accompanied by the Iliad’s Briseis (Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls, 2018), Medusa (Natalie Haynes’ Stone Blind, 2022), and the book that kicked off the current literary trend, Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles (2011).

The last follows the love affair between Greek warriors Achilles and Patroclus, and rose to popularity among LGBT youth in the 2010s for its sympathetic and open depiction of ancient male lovers. Along with Shakespeare’s Troilus & Cressida, Miller’s work even inspired the Melbourne University Shakespeare Company’s 2023 production Patroclus & Achilles. We should note, though, that depictions of same-sex love in the ancient world are by no means only a twenty-first-century phenomenon; the rose here must go to Mary Renault, whose 1956 novel The Last of the Wine centred on a paederastic couple caught in the Peloponnesian War.

The prevalence of ancient women among these new titles is a cornerstone of the new literary revival of the ancient world, and we can link it to broader global trends. The past decade has witnessed a boom of feminist consciousness – from Julia Gillard’s 2012 misogyny speech to the women’s marches following the 2020 USA presidential election and the #MeToo movement. This in turn has galvanised discussions of women in the ancient world, both in and outside of the academy.

Feminist and gender studies in the discipline of Classics have been on the rise since the 1970s and ’80s and, with female (and feminist) classicists such as Emily Wilson, Bettany Hughes, Anne Carson and Mary Beard increasingly in the public spotlight, the field is attracting new attention.

As bestselling authors such as Jennifer Saint (Elektra; Ariadne; Atalanta) and Natalie Haynes (A Thousand Ships; Pandora’s Jar; Stone Blind) continue to publish on ancient women, interest grows, and more authors and creators join the ancient party. These fresh perspectives and new inroads into the ancient world continue to keep it not only relevant but exciting.

When I surveyed first-year ancient Greek and Latin students to ask where their interest in the ancient world began, popular culture was a frequent answer. This is, after all, the generation who grew up on the aforementioned Hercules and children’s literature like the Percy Jackson series.

Students, especially those who reported a longtime interest in the ancient world, mentioned books like Percy Jackson, again and again. They also cited video games, with Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey and Hades two popular recent options, and television shows such as Barbarians, Blood of Zeus and Troy: Fall of a City also featuring.

Online spaces are increasingly influential. Some first-year language students mentioned the role played by online communities and trends in sparking their interest. The ‘Dark Academia’ online aesthetic subculture is one prominent example, largely inspired by Donna Tartt’s novel The Secret History, published in 1992 but resurging in popularity with young adult audiences in the 2010s.

Dark Academia is rooted in romanticising classic literature, the arts, higher education and tweed blazers. Dark Academia has since evolved into a literary genre of its own, inspiring novels set on university campuses and centring on protagonists who expound on Homer and Virgil as well as Shakespeare and Keats (If We Were Villains, The Maidens, Bunny).

The role of popular culture in influencing student tastes is certainly significant and there’s no denying the greater accessibility to the ancient world it grants students who might otherwise have been disengaged.

But this can’t be the whole story! After all, it would be entirely possible for students to consume all these texts without taking the trouble to learn the ancient languages in which they were originally written. Many texts about and from the ancient world are readily accessible today in English translation.

Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, epic poems which have been translated over and over for centuries on centuries, have just received acclaimed and popular new translations from Emily Wilson, with another Odyssey on its way in 2025. Most texts from the ancient Mediterranean are available in English translation.

So why, then, are students so keen to study ancient languages and undertake the somewhat daunting task of tackling ancient grammar?

Many of the students surveyed reported a longstanding personal interest in languages and linguistics, sometimes arising out of contact with ancient topics throughout their schooling. Though Latin teaching has a long history in private schools, it is no longer their exclusive domain. The latest report on Language provision in Victorian government schools (produced in 2020) found 298 students studying Latin in years 7–10 at school, with an additional 60 students studying the language via the Victorian School of Languages. These numbers are a recent increase and schools are scrambling for teachers!

One first-year student described the experience of translating ancient languages as “time travel – reading the words that people from that time wrote”, and this was a common theme throughout responses. Another student, highlighting the close contact with the ancient world that studying language inspires, wrote: “I believe that studying ancient Greek and Latin helps better understand the way people thought and acted as well as the culture of Ancient Greece and Rome in general.” One student described a feeling of personal contact with their own Greek heritage while studying ancient Greek, ancestor of the modern Greek language. In addition to these affective experiences, students consistently praised the in-depth learning and detailed understanding of ancient texts that language study enables.

Enjoyment seems to go hand in hand with the difficulty of the material. Joining a long history of ancient language students, the new cohort at the University of Melbourne loves a challenge. In student reflections on the value of studying ancient languages, the word ‘challenging’ is used in equal measure with the word ‘rewarding’. One student described the pleasure involved in learning the grammar of an ancient language and wrestling with ancient texts, which to them meant “having to piece everything together like a puzzle”.

This comment seems to me to hit the mark closely. The experience of taking what first appears to be a set of random, disconnected and confusing parts, and drawing out of it something meaningful and beautiful, is a special thrill, and a very personal one. Each translator, from the beginning student to the most expert philologist, brings something distinct to their version of an ancient text.

Ulrich Von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, the much-quoted nineteenth-century scholar known ubiquitously as ‘Wilamowitz’, famously said in an Oxford lecture that “to make the ancients speak, we must feed them with our own blood”. Studying ancient languages allows students not only to engage with the ancient world on a deep scholarly level but allows them to engage with the ancient world on an active and personal level that is uniquely rewarding.

While studying the ancient world requires effort and dedication, it also enriches our world in all kinds of ways. As the late Professor Emeritus Antonio Sagona reminds us:

Whereas it would be possible to live in a world without the Humanities, and the study of the ancient world, what a boring and meaningless world it would be – bereft of memory or imagination, or any understanding of the cultural environment that has shaped all our lives.

Current ancient languages offered in SHAPS include Ancient Greek 1–6, Latin 1–6, and Ancient Egyptian 1–4. In 2025 an exciting new (old!) language, Akkadian (ANCW 10008 and 10009, will be offered; for further information, contact Dr Tom Davies.

Ancient language reading groups are also on offer, including the Greek and Latin reading groups led by Dr Ed Jeremiah.

Natalie Haynes will be speaking on the ancient goddesses at a University of Melbourne public lecture, ‘Divine Might’, on 1 May 2025. Details can be found on SHAPS’s events website.

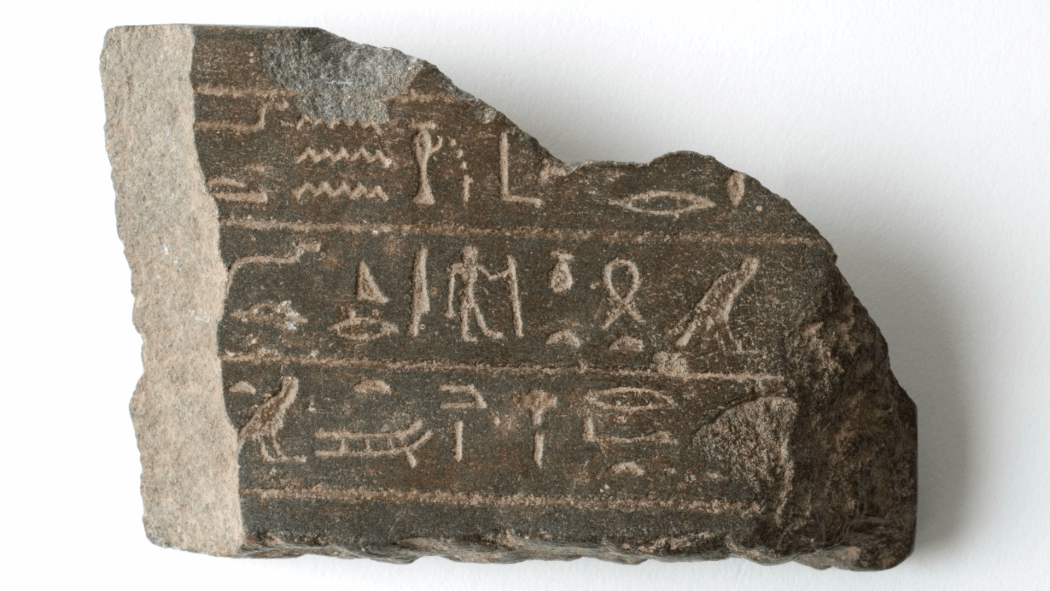

Feature image: Fragment of Hieroglyphic Inscription, Egyptian, c664—332 BCE. University of Melbourne Art Collection, Flinders Petrie Collection, 0000.0642.000.000