Out of Ancient Marshes

Archaeology at the site of the former Pontine Marshes has uncovered a massive but forgotten feat of ancient land reclamation revealing the early determination of the Romans to bend the world to their will. Dr Gijs Tol from SHAPS and Dr Tymon de Hass from Leiden University explore the discoveries on the site of the Agro Pontino in this article, first published on the University of Melbourne’s Pursuit.

In 38 BCE the Roman poet Horace set out from Rome and headed south towards Tarentum (modern Taranto) as part of an embassy on behalf of Caesar’s heir Octavian (the later emperor Augustus) aimed at making a deal with his then rival Mark Antony.

At the end of the second day of their journey along the southern roadway, the Via Appia, the party stopped to spend the night at the way station of Forum Appii, in the infamous Pontine marshes. It was a rather unpleasant experience.

According to Horace the town was stuffed with sailors and surly landlords; the water, “which was most vile” made him sick; and he lamented being unable to get a proper rest because of the mosquitoes and the constant croaking of frogs.

The next morning, he and his companions, along with all their mules and personal belongings, ditched the waterlogged roadway and embarked on a boat to take them down the adjacent Decennovium canal, to the seaside town of Tarracina (modern Terracina).

Similar derogatory descriptions of the Pontine marshes can be found in other Roman writers. Vitruvius, a Late Republican military engineer and architect, wrote:

“When the marshes are stagnant, and have no drainage by means of rivers or drains, as is the case with the Pontine marshes, they become putrid, and emit vapours of a heavy and pestilent nature.”

We now know the Pontine Marshes were once a very different place. Hundreds of years before Horace’s nightmarish stay, the Pontine Marshes had been developed by the early Romans as a thriving agricultural area. But until recently, this engineering feat had been completely forgotten.

The achievement of the early Romans is particularly remarkable given we know that much later Rome would repeatedly try and fail to tame the Pontine Marshes, even at the height of its empire. Some of the prominent failures include attempts by the Emperor Trajan in the early second century CE and the Emperor Theodoric the Great in the fifth century CE.

Even with the help of Leonardo da Vinci, Pope Leo X in the early sixteenth century failed.

It wasn’t until the 1930s that the area was finally reclaimed and colonised under Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime.

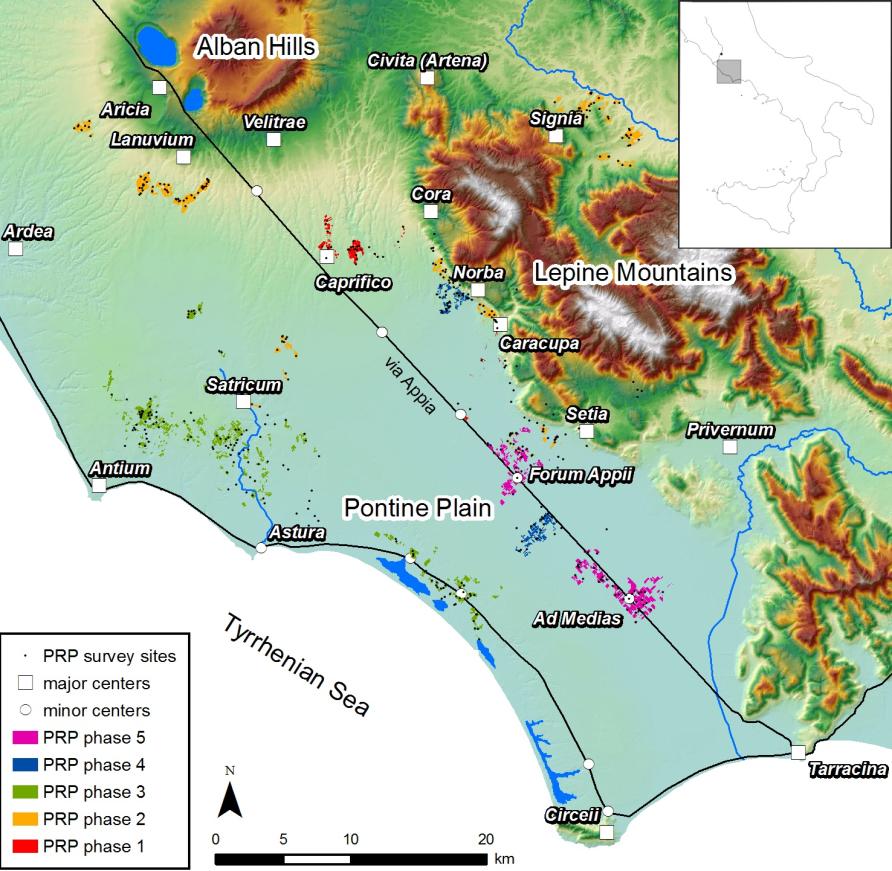

Now, more than a decade of archaeological research in this area by the Pontine Region Project, a collaborative research endeavour of the University of Melbourne and the Universities of Leiden and Groningen (The Netherlands), has revealed a deeper history of this former marshland.

It is now clear from our work that Mussolini’s efforts were preceded by – and partly built on – a long-forgotten but very successful effort to exploit the Pontine marshes back around 300 BCE when Rome was still struggling to conquer Italy.

From the historical sources we already knew that Rome had a strong interest in this area. A Roman tribe was founded in the area in 318 BCE and in 312 BCE the Via Appia was constructed straight through the wetlands.

To this we can now add the evidence from our fieldwork – a combination of geophysical surveys (ground-based techniques that use magnetic and gravitational signals to map buried archaeological features) and field surveys (in which teams scour newly ploughed fields in search of ancient cultural materials, like pottery sherds).

We mapped two way stations, Forum Appii and Ad Medias, which provided service points for those travelling along the Via Appia. Moreover, at Forum Appii we managed to identify structures belonging to the river harbour where Horace must have embarked, including warehouses and a possible quay.

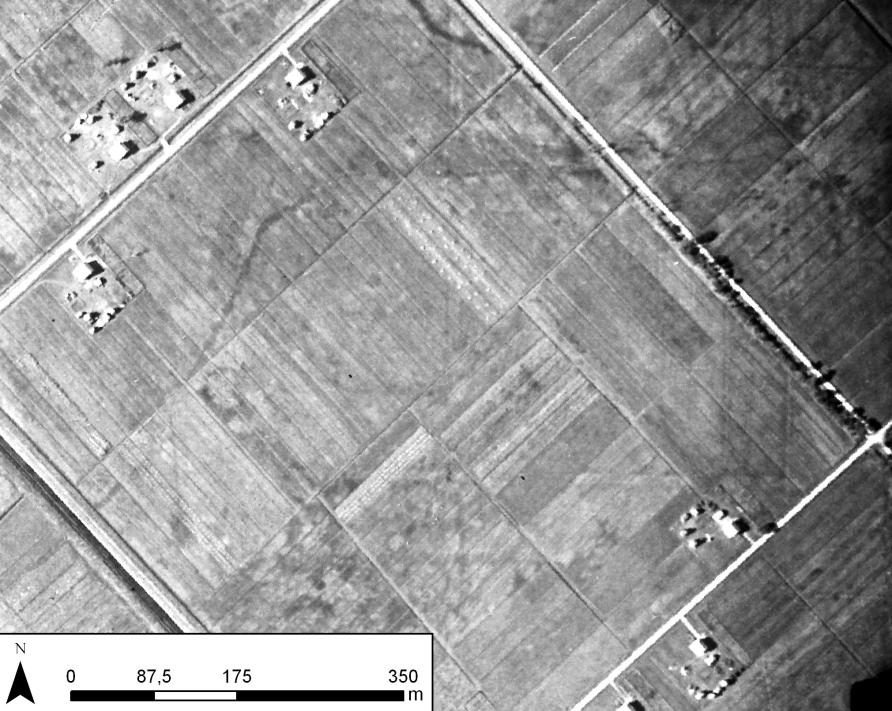

In the immediate surroundings of both way stations we found evidence of an extensive Ancient Roman land-division scheme – a centuriation – with blocks measuring about 355mx355m (or 10×10 Roman actus), covering more than 120 sq. km. The scheme included an intricate system of canals, revealed by a combination of geophysical surveys and our analysis of historical aerial images, including those taken by the Royal Air Force for aerial bombing during the Second World War.

Through borehole/coring studies we know that these canals, which would have drained the land, include a series of small (one to two metres wide) channels that fed into larger ‘arteries’, which in turn discharged into the Decennovium Canal on which Horace carried on his journey. Radiocarbon-dating of remains from these canals now provide further evidence that this reclamation system should be placed in the early Roman period.

It had clearly been a densely settled agricultural landscape. We’ve found closely spaced farmhouses organised along the lines of the centuriation system, and the highly standardised pottery assemblages associated with these farm sites (consisting of roof tiles, transport amphorae, cooking pottery and fine tablewares) suggests that the development of this area was sudden, occurring around the turn of the fourth century BCE.

We know this because of the closely datable stamps on the large amount of black slipped ceramic table wares we’ve found that is characteristic of the late fourth and early third centuries BCE.

Taken together, our investigations suggest that this former wasteland was completely redeveloped around the same time the Via Appia and the Decennovium Canal were built. Moreover, our work suggests that around the same time the road stations of Forum Appii and Ad Medias were founded, along with many surrounding small rural sites.

The scale and complexity of the project suggests that it must have been a state initiative. It would have involved the large-scale displacement of people and an extensive program of public works, including roads, canals and ditches. This undoubtedly required enormous resources, both financially and in terms of manpower and technical skill.

A large-scale undertaking like this makes sense at this time. It created an important transport corridor to the south that paved the way for the military conquest of Campania, and eventually all of southern Italy.

By reclaiming the Pontine marshes, the Romans established a regular system of support points along the Via Appia, as well as opening up an extensive agricultural area close to the city. Rome may well have been in urgent need of more farmland as the city grew and the army needed more landed recruits.

In the end, the success of the redevelopment of the area was relatively shortlived. In the lowest lying part of the marshes many farm sites were abandoned after only a few generations, possibly due to poor maintenance of the drainage system. By the first century the Via Appia had become so mired that travellers like Horace preferred to travel by boat.

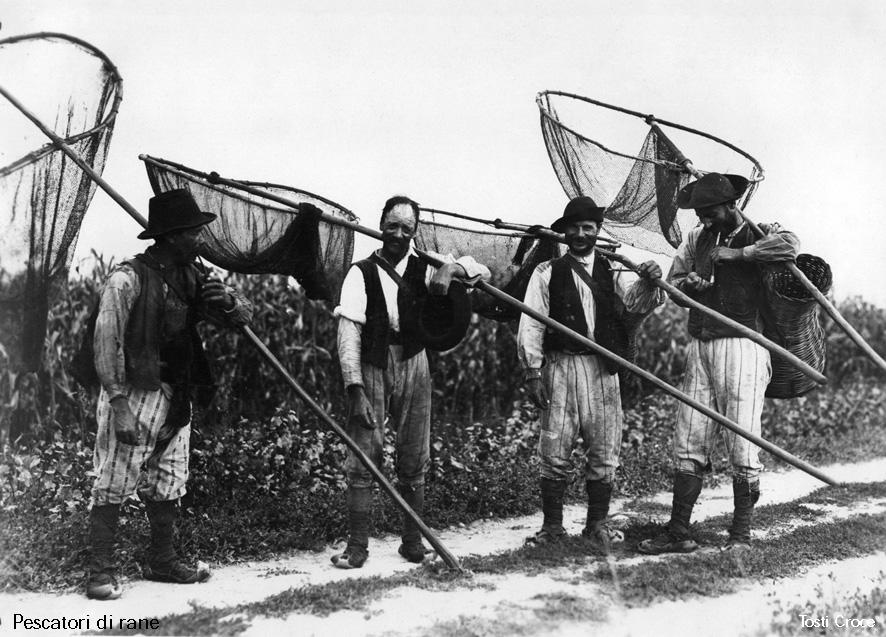

Our field surveys indicate that parts of the area were eventually given over to a wide range of small-scale economic activities that exploited the natural resources of the wetlands, including the seasonal herding of flocks, fishing, pottery production, as well as the fattening of dormice, considered a delicacy in Roman cuisine.

Dormice were bred in tall ceramic pots called gliraria (from glis – Latin for dormouse), examples of which we found during our surveys.

By Horace’s time, living and working in the Pontine marshes must have closely resembled the situation just before Mussolini’s reclamations, when the area housed several small villages, and the inhabitants lived on small-scale agriculture and livestock grazing. The wetlands were also home to activities like fishing, frog catching, hunting, charcoal burning and wood cutting.

But well before Mussolini and Horace, the Pontine Marshes already housed a thriving agricultural community. And while that achievement has long been forgotten, we now know with the benefit of hindsight that it was an early sign of the determination and engineering skill that would help build the Roman Empire.

Feature image: Leonardo da Vinci’s plans of the Pontine regions drawn as part of his work for a papal scheme to drain the marshes, c1514–1515. Royal Collection Trust