Racial Justice, Memory & the Museum

In December 2019, History PhD candidate Sam Watts travelled through the Deep South completing research for his thesis on racial politics in the Reconstruction-era urban Deep South. Here he reflects on this trip, historical memory, the nationwide protests following the murder of George Floyd, and the ongoing struggle for racial justice in America.

The day before I flew out of the United States in December 2019 I stopped in Montgomery, Alabama, to visit the National Memorial for Peace and Justice – dedicated to black victims of racial violence in the United States – and the Legacy Museum, both founded and run by the Equal Justice Initiative. It was the end of an intensive two-week tour of archives and museums in eight cities across the Deep South, my fourth and final research trip for my PhD thesis. From university library basements, to state archive buildings and the backrooms of local historical societies, I had been looking into the history of African American daily life in the Deep South during Reconstruction – the decade following the collapse of the Confederacy in 1865.

In this brief period (1865–1877), between slavery and the rise of Jim Crow segregation, African Americans seized the economic, political and social opportunities guaranteed by the federal government to take control over their lives and communities in ways that would have seemed impossible only a few years earlier. As I document in my research, formerly enslaved men entered local and state politics, became police officers, judges and lawyers. Formerly enslaved women not only were the driving force behind the construction of many black community institutions which live on today, but fought simultaneously for women’s and black civil rights.

In the leadup to my trip to Montgomery, I spent time in various museums and archives, talking with curators, tour guides and other researchers about both the incredible achievements of formerly enslaved people and also the brutal violence inflicted on them by white Americans during these years. In Vicksburg, Mississippi, I had the privilege of spending an afternoon with the curator of the city’s African American history museum, Yolande Robbins, who talked about how her great grandparents survived both slavery and the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) during Reconstruction. She talked about how the threat of lynching continued into her lifetime, her experience as a young woman desegregating the city’s restaurants and her role now as an eighty year old woman in educating school groups and visitors about this history.

In Savannah I was able to visit the Davenport House – a historic house museum which, unlike the dozen or so other house museums I have visited, began its tour in the slave quarters and with a mural naming every enslaved person who lived or worked at the site. In Tuscaloosa, I caught up with a friend who runs alternative campus tours of the University of Alabama – tours which are focused on the history of the university and its buildings from the perspective of the enslaved people who built them and which highlight the role of the university in maintaining white supremacy into the twentieth century.

These examples of public history which centre the lives of African Americans and address legacies of violence and intimidation are unfortunately rare, and they are not representative of the conventional historical narratives which are presented to visitors across the Deep South. While some are better than others, small museums, commercial tours and historic sites generally are far more likely to present a romanticised and thoroughly whitewashed historical narrative. These organisations are usually run by local volunteers and, just like their clientele, are overwhelmingly older and white, so this perspective should not be surprising.

Yet, as cities across the US continue to be enveloped in protests over the murder of George Floyd and broader issues of police brutality and systemic racism, these museums and historic societies have a duty to confront the legacy of historic racial violence and contextualise the brutality on display in the murder of Floyd, in the police and military’s treatment of protesters and in President Donald Trump’s recent rhetoric.

In Montgomery, both the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum highlight how histories of horrific violence and prejudice can be taught and communicated productively and powerfully. While the museum guides visitors through an immersive historical narrative from slavery to mass incarceration, the memorial consists of 800 steel sculptures, representing every county in the United States where a lynching has taken place. The morning of my visit to Montgomery, I had visited one of those counties – specifically the site in Mobile where Michael Donald’s body had been hung. The nineteen-year-old black student was chosen at random by three members of the KKK, driven out of town, murdered and then hung from a large tree in a quiet residential street in downtown Mobile in March 1981.

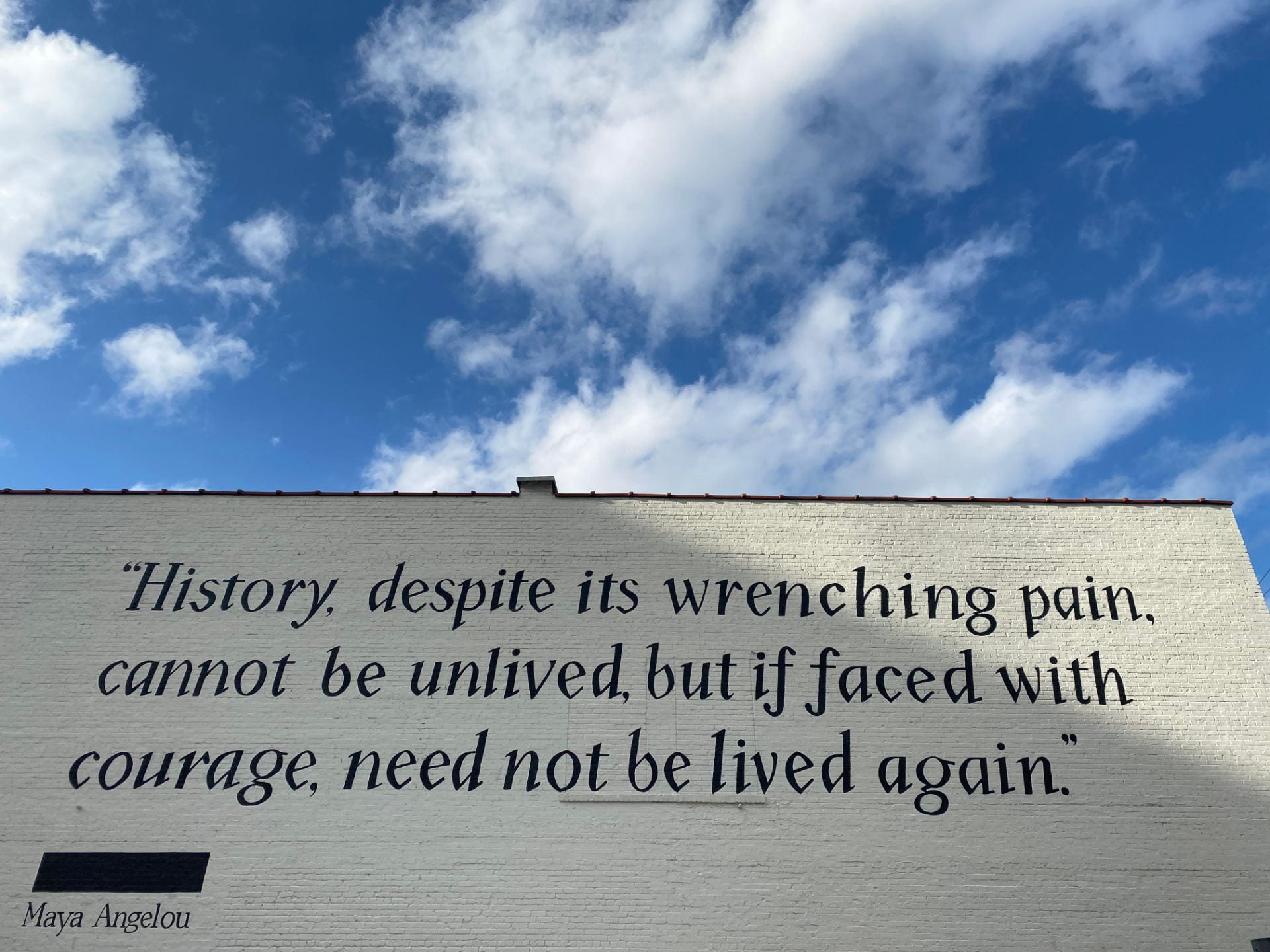

In the weeks leading up to my visit, I had been to multiple museums which either failed to confront the entirety of the historical narrative or, worse, as at the neo-Confederate Old Court House Museum in Vicksburg, dealt in ugly racial stereotypes and portrayed slavery as essentially a beneficent institution. To finish my final research trip by visiting the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum – two Equal Justice Initiative sites, which not only confront the history of racial injustice directly but are founded on concepts of restorative justice and reconciliation – was a humbling and deeply emotional experience. Both these sites demonstrate the power of an effective historical narrative to confront the past, deal with traumatic historical memory and provide an avenue for reconciliation and, ultimately, justice – for George Floyd, and for all those who came before.

Sam Watts is a PhD candidate in History and researches and writes about the experiences of African Americans and the politics of daily life in the urban Deep South during Reconstruction. He has recently returned from his fourth and final thesis related trip to the South – with his research and conference travel generously supported by the Faculty of Arts and SHAPS and the History department at the College of Charleston. Sam was awarded the Ian Robertson Travel Prize for his most recent trip, allowing him to visit archives across four states and eight cities. Sam is the author of a forthcoming chapter on African American police officers in the 1860s and 1870s in the edited collection, Freedoms Gained and Lost: Reconstruction and Its Meanings 150 Years Later (NY: Fordham University Press, 2020). Sam is the co-founder and managing editor of ANZASA Online, an American studies blog.