Graham Berry, Democratic Adventurer: An Interview with Professor Sean Scalmer

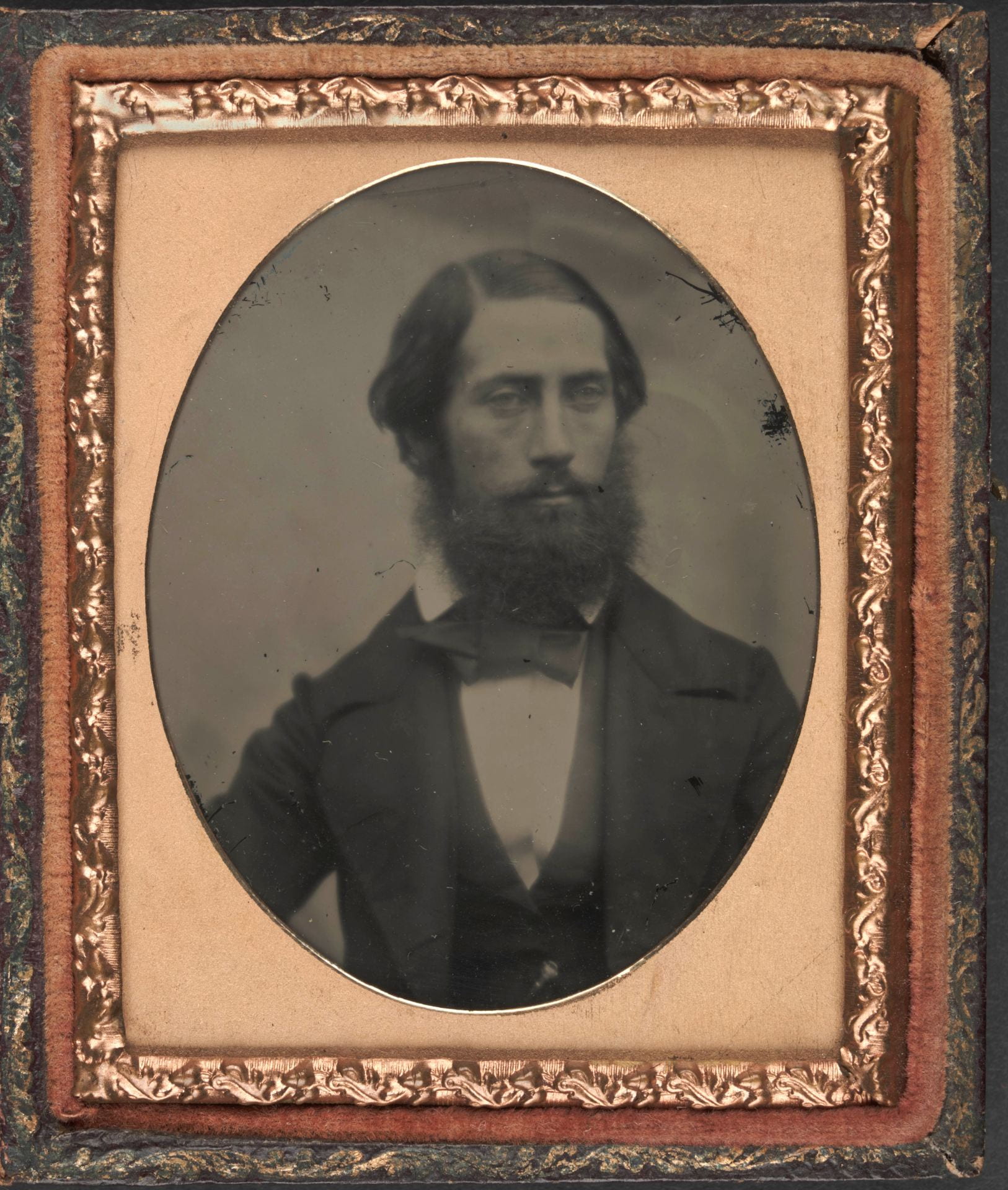

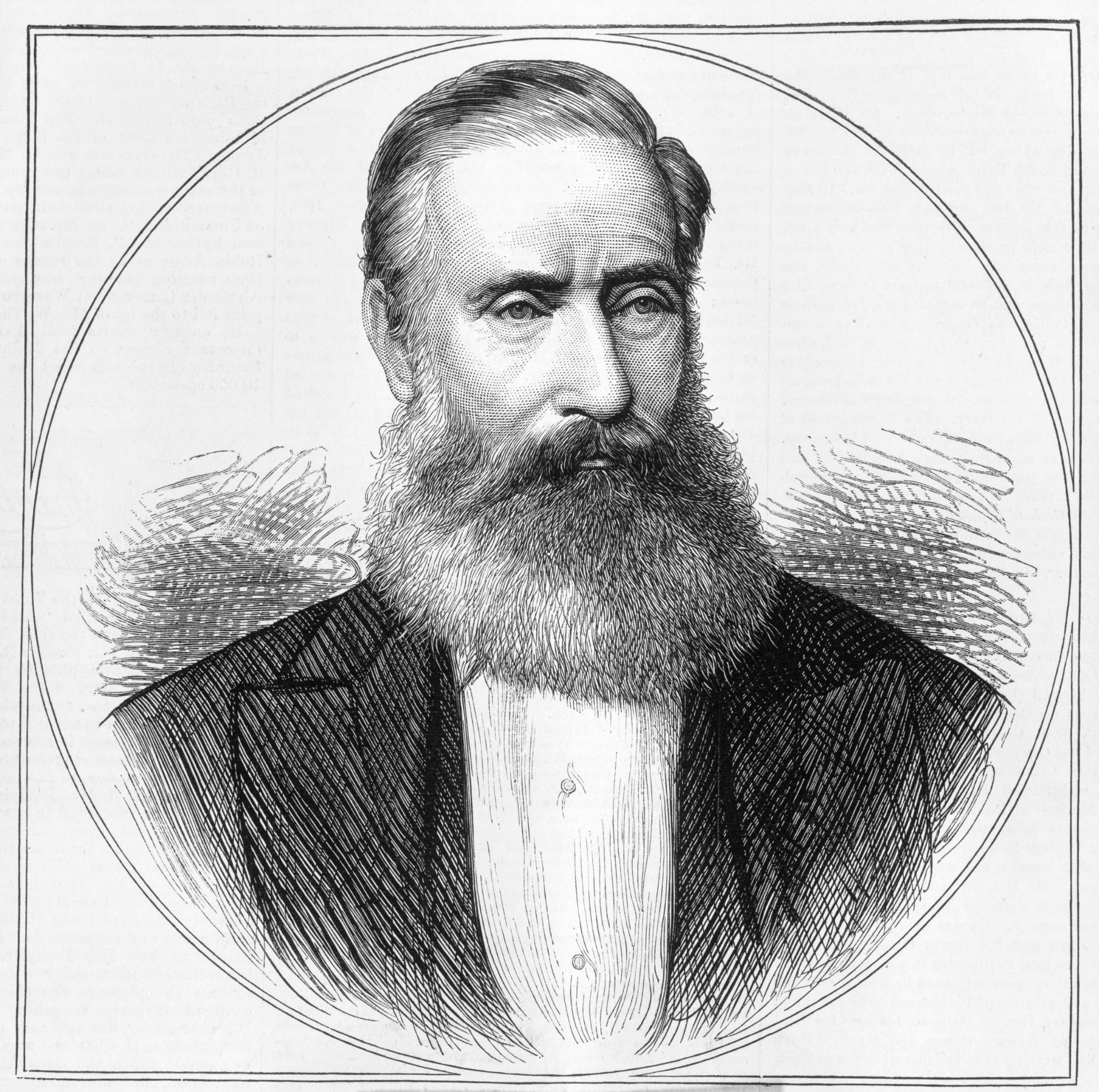

Sean Scalmer, Professor of History in SHAPS, has just published a new book on the nineteenth-century Australian political figure, Premier of Victoria, Graham Berry. Democratic Adventurer: Graham Berry and the Making of Australian Politics tells the story of Berry’s ‘remarkable rise from linen-draper and grocer to adored popular leader’, and his role in shaping Australian democracy. History PhD candidate Jimmy Yan had a conversation with Sean about the book, Berry’s life and why we should care about nineteenth-century Australian political history.

Listen to the podcast on the player below or head to your favourite podcast site for the first of our SHAPS Forum podcasts.

For a 20% promotional discount on Democratic Adventurer, enter the discount code PUBGEN20 when purchasing your copy via the Monash University Publishing website.

Jimmy Yan is a PhD Candidate in History researching radical imaginings of ‘Ireland’, contentious politics, and settler ambivalence in Australia, 1912–1923.

Transcript

Welcome everyone to the SHAPS podcast – I’m Jimmy Yan, a PhD student here in History. Today we’re talking political history, and we’re joined in perhaps more socially distant circumstances than normal, by Professor Sean Scalmer.

Sean is a newly promoted Professor of History here at the University of Melbourne, and also a Deputy Associate Dean in the Faculty of Arts. Sean is the author of numerous books on the history of social movements and the history of political activism. These include: What If? Australian History as It Might Have Been (2006); Gandhi in the West: The Mahatma and the Rise of Radical Protest (2011); Activist Wisdom: Practical Knowledge and Creative Tension in Social Movement (2006, with Sarah Maddison); and The Little History of Australian Unionism (2006). Sean recently won the NSW Premier’s History Award for his book On the Stump: Campaign Oratory and Democracy in the United States, Britain, and Australia (2017). But within just a couple of years after winning that prize Sean has come out with a new and equally groundbreaking book. We’re here today to talk about Democratic Adventurer: Graham Berry and the Making of Australian Politics (2020), Sean’s fittingly titled biography of late nineteenth-century radical liberal and social reformer, Graham Berry.

Graham Berry was the premier of Victoria, a founder of the Australian protectionist movement, and an oft-overlooked figure within the history of radicalism in Victoria.

So, Sean, welcome to the podcast!

Thank you.

Let’s begin by talking about your new biography of Graham Berry. In many ways, you have redressed a lacuna within an Australian political historiography that overwhelmingly centres on the post-Federation period. What first got you interested in Berry’s life?

Yeah, I think you’re entirely right that much of our political history does focus on the twentieth century, and I suppose one of the things that drew me to writing a life of Graham Berry was an attempt to counter that. I think the nineteenth century is an enormously interesting period in Australian political history, precisely because it combines two elements of Australian history.

One is the story of, I suppose, precocious advance – the notion that the suffrage which was extended to white working-class men in Australia earlier than most other places and, equally, white women won the franchise earlier than most other places; and that there were a number of reforms passed, and experiments waged, by Australians. So the nineteenth century is interesting for that reason, as a kind of more positive story of experiment and advance.

But of course it’s also a moment of racial exclusion, and what we think of as democracy was obviously defined by the racial subordination and exclusion of Aboriginal people, and marked by campaigns that attempted to exclude Chinese people from Australia.

So I was interested in going back to that period of nineteenth-century history because of those two elements. And, I suppose, I’d written earlier, as you noted, this history of stump oratory in Australia, the United States and Great Britain, and in that book, which was also about the nineteenth century, I’d come across and become fascinated with Graham Berry as a person.

So this is someone who arrives in Victoria in 1853, he sets up as a grocer, and then enters politics, with great difficulty; he is a radical figure, a scourge of the Establishment; and a fascinating figure. One of the things that’s fascinating about him, and one of the few portraits of him that reaches our time is Alfred Deakin’s beguiling memoir, The Crisis in Victorian Politics. And Deakin describes Berry at one point as “a dictator of Victoria; someone who held absolute power”. And he also recalls telling Berry that he held absolute power, and Berry responding: “Yes, at one time I did hold absolute power, but only on the condition that I did not use it.”

And that portrait of Berry, and that phrase of Berry’s – Yes, I held absolute power, but only on condition I did not use it – was enormously fascinating to me, and it opened up this sense that Victorian politics in particular was this place of democratic ferment, and that Berry’s life and Berry’s struggles might offer a special insight into it.

So those things sort of connected and brought me to the idea of writing a biography of Graham Berry. On the one hand, an interest in nineteenth-century history and wanting to make that history live, for contemporary readers; and on the other, a particular magnetic pull of Berry’s personality.

Thinking now about Berry’s political outlook and political aims; what were Berry’s major contributions to the history of nineteenth-century democracy in Australia?

Well, he’s an innovator in politics. As I said, he comes to Victoria and sets up as a grocer, and he’s always on the one hand trying to advance his own interests – so, he is ambitious for himself, he wants to take advantage of the new possibilities for someone like him, the fact that there is no longer a property restriction for white men and that white men can vote and stand for office. He wants to take advantage of that; he wants to enter parliament and make laws.

But at the same time, he’s facing a series of challenges. Although class formally isn’t meant to proscribe involvement, there’s a sense that political power is most appropriately wielded by those who are not of the trading classes or the working classes. So his aim in part is to try and win power for himself but, precisely because he’s someone who is from a working-class, lower-middle-class background, that effort to win power for himself is also a kind of a broader challenge. Part of the reason that he’s able to win a lot of support is that he symbolises the idea that so-called “self-made men” might become important in the self-government of the colonies.

So his contribution is partly just the fact that he does seek to win power and that in seeking to win power and successfully retain power, he represents a kind of a model or an imaginary for others. But his contribution also lies in practice and in policy.

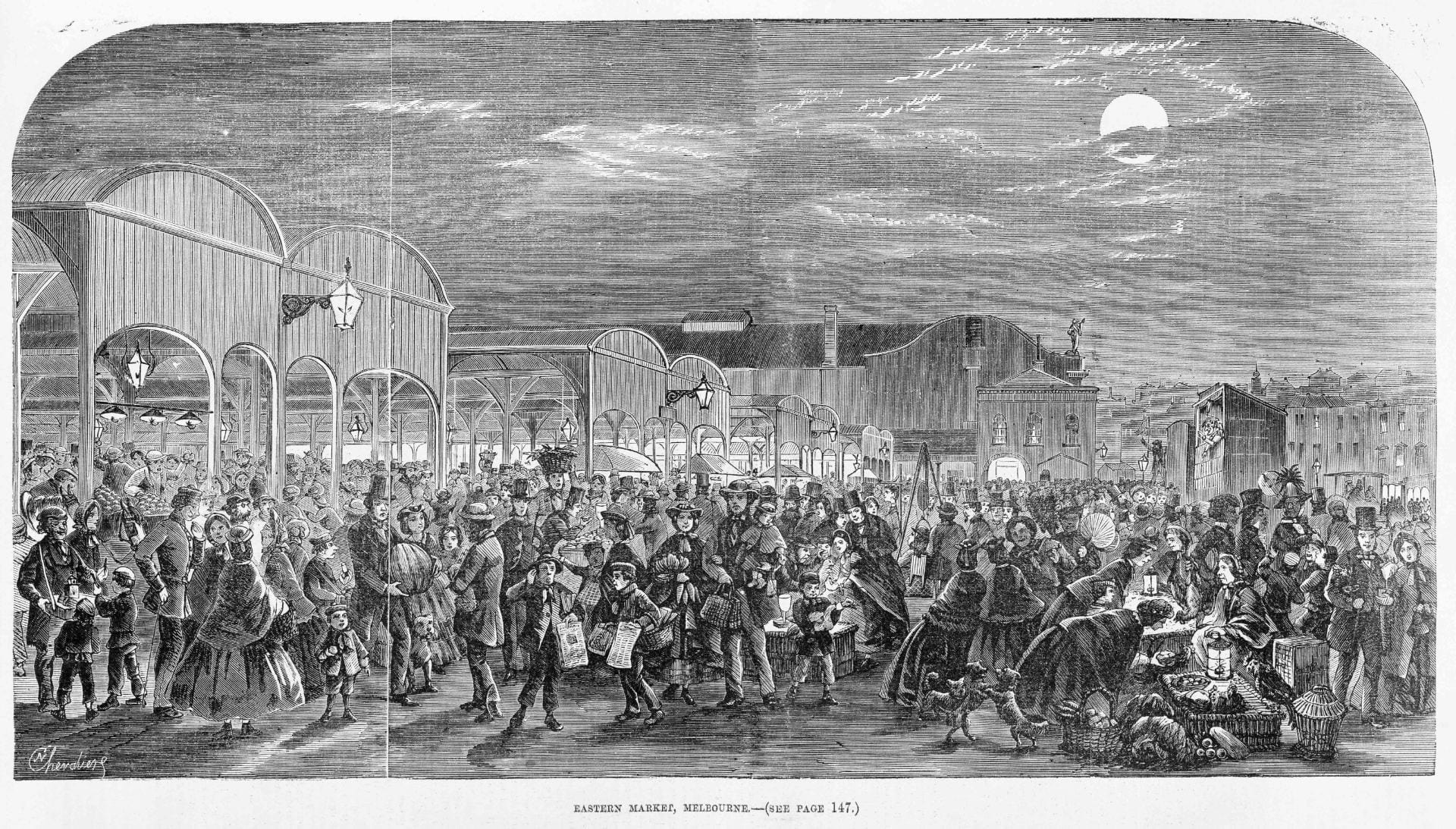

His contributions in practice are that precisely because he doesn’t have money, he doesn’t have resources, he’s not respected, he needs to find ways to convince others to vote for him and to wield power. And so he experiments with a whole range of methods. There are other people in his position, other working-class Victorians, Victorian men, who are assembling in a place called the Eastern Market, in the centre of Melbourne, from the late 1850s, and this is where he enters politics. He becomes someone who is a radical outdoor speaker, and part of his contribution to politics from the late 1850s but throughout his career is to affirm the importance of radical oratory, outdoors oratory often, as part of democracy. So what we think of often as the right to free assembly, he’s someone who’s advancing that and enacting it across his career.

He’s also someone who’s, in the realm of practice, experimenting with the political party as a form. We think of the political party as part of the furniture in political life, you know, in a sense as something that has always existed, but of course the idea of a mass political party was initially controversial, and the way you would run and create a mass party needed to be discovered. And Berry was formative here. So he’s the person who sets up the first mass political party in Australia, and well before the Labor Party, called the National Reform and Protection League. This is a party that at its peak had more than 150 branches, it had a central branch that ran preselections, it had a common platform, its members met together as a caucus. And Berry was the founder of that party, the president of that party, and the parliamentary leader of that party; and bringing those things together was entirely novel and created precedents for later parliamentary politics and later mass politics in Australia.

In the policy sphere, I suppose he’s identified with a couple of policies. Most importantly, he’s identified with the policy of protectionism. So that is, the idea that the government, the state, should levy special taxes on certain categories of imported goods so as to create a wall or a shield for Australians to create those goods and to sell those good. And an important idea behind protectionism in Berry’s hands was that it would be a mechanism to ensure that Australia could set up its own manufacturing industry, and that it could employ urban craftsmen at good wages. And he pushes this policy from the late 1850s, all the way through his career. He’s the leading spokesperson for protectionism. He buys a newspaper that pushes protectionism, the Collingwood Observer; he buys another newspaper, the Geelong Register, to push protectionism; as I said, he leads the party that advocates protectionism, he becomes the first treasurer to implement a genuinely protectionist tariff; and as Premier he pursues protectionism.

So it’s often thought that David Syme, the owner and editor of the Age newspaper, is the kind of, the term’s often used, the ‘father of protectionism’ in Australia. But what I try and argue in my book is that Berry is a more important and certainly an earlier champion of this policy. So he’s important and makes a contribution through pushing protectionism.

As I discuss in the book, he links, from the 1880s, protectionism to the cause of racial exclusion and opposition to Chinese immigration; so he’s associated with linking together protection of the economy and racial exclusion. And he also pushes in various ways for policies that are going to reform the Constitution and to move it in what most people would consider a more democratic direction. So the colonial constitutions in Victoria and in other colonies that were established when responsible government was ceded to the colonies from the late 1850s, these constitutions had in practice a mass franchise for white working-class men for the lower house, but for the upper house, they weren’t open to the mass votes of the people.

Now the systems were different in different colonies, but in Victoria there was a restricted property franchise for the upper house, so that the … electorate for the upper house was one tenth of the size of the electorate for the lower house. And the upper house had a great deal of power and was able to continually block legislation. And Berry suggested that in the first twenty-five years of responsible government about eighty major bills were blocked by the upper house in Victoria.

So one of the things he tried to do throughout his career, but especially as Premier, is to try and cut back the power of the upper house, with the idea that this will allow the lower house, the people’s house, in his view, to make laws without the intervention of powerful class-based interests.

So he’s associated with those things, also tied to pushing for democratisation. He’s associated with the quest for members of parliament to be paid, with the idea that if you weren’t paid to be a parliamentarian then only the rich could afford to enter parliament.

Brilliant. You mentioned that Graham Berry’s life offers a different perspective on this history to that of David Syme. What was the relationship between Berry and the broader colonial liberal milieu? Did Berry have any relationship with Syme?

Yes, absolutely – they had a relationship. It was a tumultuous relationship. So as I said, when Berry enters politics, and as he becomes more prominent, he’s still seen as marked by his origins. So in England he’d been apprenticed as a linen draper, he’d come out and set up as a grocer, and as a wine and spirit merchant, and for many of the well-born and better educated in the Australian colonies he was seen as a parvenu, he was seen as someone who didn’t really have the right to exercise authority. And so many of the leading politicians looked down their nose at him; and David Syme and the Age definitely looked down their nose at Berry. When Berry started championing protectionism in the late 1850s the Age at that time was opposed to protectionism, and it was quite scathing of Berry. When the Age began to embrace protectionism and there was greater agreement on policy, there was nevertheless a continuing sense of ambivalence on Syme’s part and on the Age’s part. And this was magnified on a number of occasions, most notably in the middle-1860s.

So by the middle-1860s, partly due to Berry’s advocacy, a government is elected which does pursue a policy of measured protectionism. And that’s a government led by [James] McCulloch, with [George] Higinbotham as the Attorney General and leading animating spirit. And that government tries to impose a tariff, that the Legislative Council rejects. The government embeds it in an appropriation or supply bill, and the upper house rejects that, so there’s a kind of a crisis where the government is going to run out of money because the Legislative Council has refused to pass its appropriation bills or money bills … and, in that context, a crisis that runs over a number of months, Berry ends up criticising McCulloch and Higinbotham, primarily for their tactics, and criticising them openly and breaking with them. And when he breaks with them the Age turns on Berry, and more or less hounds him out of politics. And he’s defeated for his seat that he then holds in Collingwood; he then moves to Geelong to try and revive his political career, but even in Geelong every time he stands for office, the Age goes after him, says he can’t be trusted, and Berry in turn is highly critical of Syme and the Age.

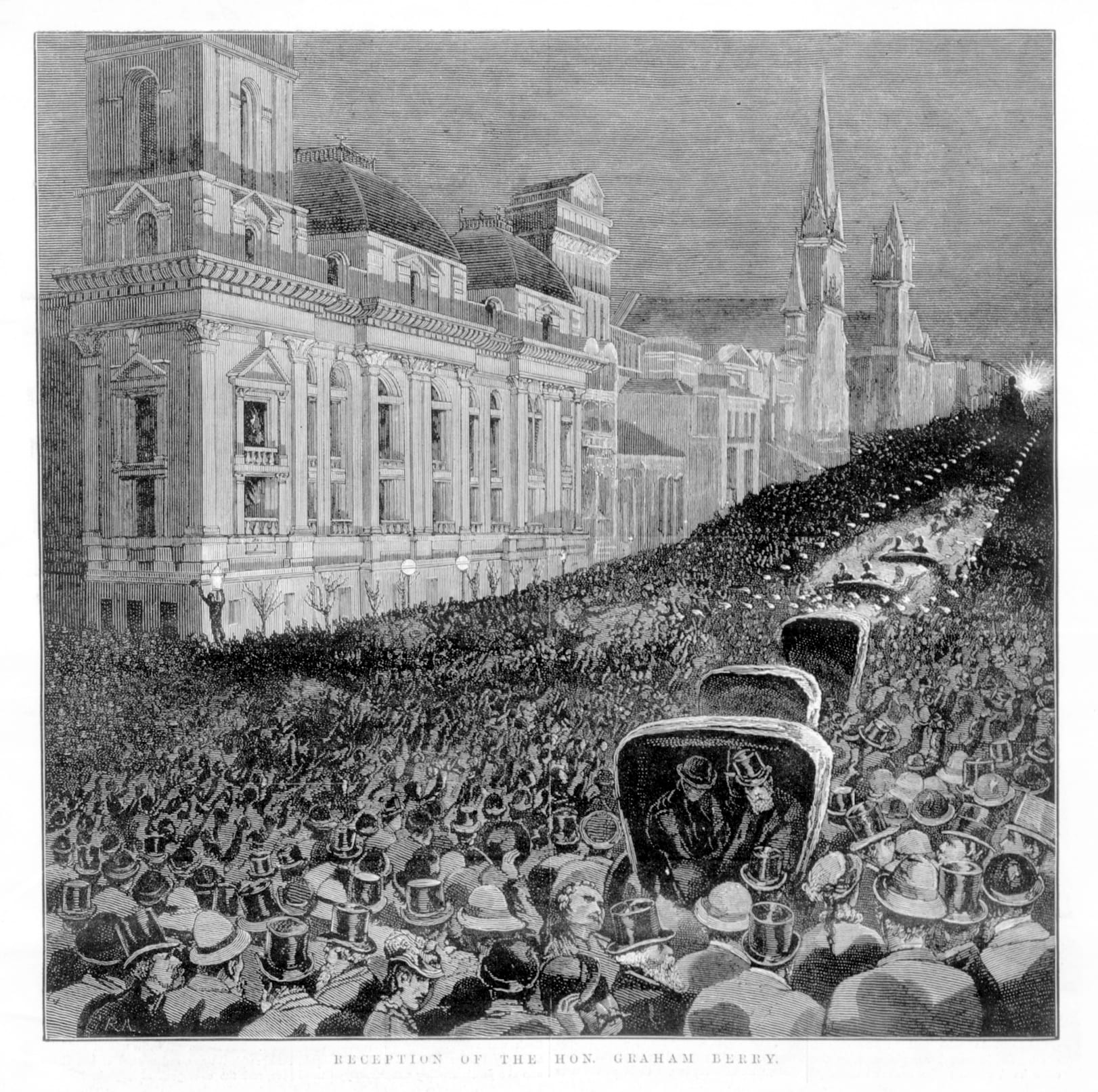

There is a period of rapprochement that happens in the middle-1870s, when the Age sees that by this stage, Berry is the primary figure that’s associated with the values it holds dear by that stage, which are for a form of liberalism or social liberalism, with a role for the state supporting protectionism, supporting greater democratic reform. They’ll support Berry over 1875, 1876, 1877.

But then when Berry wins power in 1877 with a thumping majority, the Age begins to flex its muscles more, and to be increasingly critical of Berry’s government, so that there is a fracturing of that relationship between Berry and the Age, and each of them in a sense are struggling for pre-eminence. Each of them are aspiring to be the leading voice of democratic reform in the colony, and they’re jealous of each other. Somehow because of that jealousy there are constant attacks, constant sniping, that ultimately weakens the movement for democratic reform, and is part of the reason, though not the entire reason, part of the reason why the movement for democratic reform loses some of its energy in the early 1880s.

Beyond the local response to Berry, from Victoria, what was the response from the metropole to Berry’s political projects and his premiership?

This is one of the many I think interesting parts of the story. So at this time, remember, this is the part of the story where the Australian colonies are relatively precocious and advanced, in international terms, so there is manhood suffrage in the colonies, even if it’s marked by racial exclusion, and that’s not the case in Great Britain, in the metropole. And that means that the liberals of the metropole look towards the colonies hoping for vindication of their hopes in a wider franchise. And it also means of course that the conservatives of the metropole look to Victoria for proof that you should not enfranchise the masses because if you do there will be great political instability, and ne’er-do-wells and demagogues will rise to power. So when Berry wins office for the first time, the conservatives of the metropole say: Aha! Here’s proof of what will happen! And they describe his first ministry I think as the most unscrupulous gang ever to hold office in the British Empire. And during the first major period of Berry’s government – the second government of Berry’s which is elected in 1877 – when this government of Berry’s takes power a new round of conflicts between the lower house and the upper house is enacted. And again there’s an attempt by the upper house to throw out appropriation bills and to starve Berry’s government of financial support.

And in the teeth of this conflict, Berry adopts a highly radical approach. What he does is he says: well, upper house, if you’re going to deprive us of the money in order to run our government, we’re going to sack all of the senior civil servants in the colony. And in early 1878 that’s what he does, without any warning, several hundred senior civil servants, including county court judges, are all sacked. And that becomes known as ‘Black Wednesday’. And the metropole, of course, gets this news and, as I said, the conservatives in the metropole see this as a proof that you cannot have a mass franchise, that what happens, if the workers get their hands on the government, then you’re going to have a revolution. And they describe it as a coup d’état, as a Victorian revolution, etc., etc. They compare it to the French Revolution, to the Paris Commune.

So there’s a great deal of critical commentary about Berry’s government, from the metropole; but it’s more than just commentary, because Australia’s political arrangements at that time continue to give the British government important power over what happens within the colonies. And Berry attempts to take advantage of this, and explicitly tries to draw in the metropole, into his attempts to make democratic reform.

So if I could just sort of go back a few steps: one of the things that Berry’s government tries to do from 1878 is to attack the power of the upper house, and to introduce a form of constitutional revision, or constitutional reform, that’s going to limit the capacity of the upper house to as they see it meddle in the workings of the lower house. So they want the upper house not to be able to refuse appropriation bills and supply bills, and they also want – although this is especially controversial even among liberals – they want a constitution that will allow for a form of plebiscite, so that when there is disagreement between the upper house and the lower house, they want that matter to go to the people, that is, the people who can vote, and for them to express a view, and for that view to then determine whether something can become law, or a bill can become law or not.

Now, Berry’s plans for reform are blocked by the upper house – actually they don’t want to allow a constitutional revision that’s going to reduce their power, and so Berry says: Alright, well, if that’s what you’re going to do, I’m going to go to Britain – and he calls it an ‘Embassy to Britain’, to try and change these arrangements. And he says: I have to do this, because the British have set up a constitution for Victoria which gives the Legislative Council, the upper house, so much power that I can’t actually change it. So the British need to understand what it is that they’ve done, and they need to intervene so that there can be some kind of constitutional revision, a new constitutional settlement. And he sets off to Britain, and arrives in early 1879 on this embassy to try and convince the British government to intervene on his behalf and to allow for some kind of challenge, and hopefully to allow for his bill for reform to become law.

What happens of course is that he’s greeted by a British government that’s strongly conservative in nature. This is Disraeli’s ministry, and the Secretary of State for the Colonies has absolutely no interest in supporting democracy. He’s not a supporter of a mass franchise in Britain and he’s certainly not going to try and support those associated with a mass franchise and greater democratisation in the colonies.

At the same time, people in Britain are caught up with other things going on with their empire, including a challenge to British control in Africa, the so-called Zulu uprisings [the Anglo-Zulu War], just as Berry arrives. So his embassy is a complete failure; he doesn’t get the government in Britain to take his side in this constitutional dispute, and he goes back a much diminished figure. And so it’s not just that Britain and many Britons are critical of him and see him and his government as proof of the dangers of a mass franchise; it’s also true that his attempt to call Britain and British elites into the dispute on his side is another failure that contributes to the eventual defeat or disappointment of his quest for genuine reform.

Turning now from Berry to yourself, Sean Scalmer, you’re a historian of political activism and social movements. Thinking now about your overall career, how does your major study of Berry relate to your earlier work? Could you talk about your own path as a historian?

I’m sure it will be rather garbled from book to book … There’s not a grand plan where I set out in a certain direction to systematically work towards it. But as you say, I’m someone who’s interested in political change, and in social movements in history; and as you observed in the introduction, my first few books were studies of twentieth-century politics especially, and of contemporary social movements and their influence on democracy.

But as I’ve worked away on the problems of social movements and democracy and activism and democracy, I’ve increasingly come to the view that the preoccupation with the post-’68 social movements blinds us to the importance and to the lessons we might learn from earlier eras and earlier forms of social movements.

And so that led me, first of all, to a study of Gandhian politics and the influence of Gandhian politics, and Gandhi’s political experiments in Africa and India, on western social movements. It led me to a greater number of studies on nineteenth-century social movements of various kinds, and to the question of politics and performance. And that was my book On the Stump – it was an attempt to think through, well, if we don’t just think of democracy as a series of rules, and a series of laws, but instead a series of performances, and we think about social movements and protests as forms, as version of performance, then we might also think about election campaigns as political performance. We might try and uncover and understand how they developed as performances, how they shifted, and how a version migrated from one location to another, and how that happens, and what the implications of borrowing and adaptation were. So that got me interested in those things, and as I said, that concern with nineteenth-century borrowings, nineteenth-century experiments with political performance, and the relationship between Australia and the wider world, in turn, got me interested in Berry.

I suppose as well, because I’ve become so interested in the notion of politics as performance, I’ve been increasingly drawn to closer, more specific studies of particular individuals as exemplary of certain political performances, and also as kinds of political symbols that exerted an influence on activists and observers at the time as well as afterwards. That was in my book on Gandhi, my book on nineteenth-century electioneering, and I thought, well, why not, given that Berry was so interesting, why not study him as a figure who hasn’t been examined closely before in a book-length study? Why not examine him in real depth, and try and develop my own skills in understanding the construction of a political career and a political subjectivity?

What is the value of biographical method more broadly for the historian of political movements?

There are I think probably two things that draw me to the biographical form, and its possibilities. One of them is the inspiration of someone like Robert Caro, the American historian famous for his studies of Robert Moses and LBJ [Lyndon Baines Johnson], and reflecting on his own project, Caro has said that he doesn’t see his biographies simply as studies of particular individuals, but rather as attempts to understand the workings of political power. And that was definitely the impetus behind my particular approach to the political biography of Berry.

I thought, contemplating his career – its arc from the early 1850s through to the late 1890s – I thought here is an opportunity to think through an era of a grand experiment with a mass suffrage; the possibilities that it was invested with, the ways it could be wrenched into new forms, and to think through how an enormously creative figure, a determined figure and an ambitious figure might attempt to use the possibilities of a mass franchise for himself and for others like him. And also to try and find and think through the limits of that kind of politics: what are the limits to the power of someone who wants to use a mass franchise and a parliamentary democratic system? And as I said, one of the things the book confronts is that even though Berry is enormously creative, even though he’s able to do things like create a mass party, win arguments through powerful oratory, win mass support – even though he has all these resources, ultimately his quest for reform, for a reform that he wants, isn’t successful.

And so I wanted to think through the limits of parliamentary politics and the ways in which constitutional power, existing political power, but also economic power – the possibility of a capital strike, which is what Berry’s government faced – the way all of those forces can limit the power that’s open to those who want to use parliamentary politics. So that’s one appeal and one interest of using the biography as a form. It’s providing an opportunity to get an insight into the kind of micro-dynamics of power, and the interplay of structure and agency, as creative figures try and win their demands.

The other thing is audience – that despite the views of many outside the academy that, you know, people who work in academic departments are always content to be in an ivory tower and to write only for experts, I think most historians aspire to reach a wider audience – certainly I do. I try and write my books in an accessible way, an engaging way; but I thought, well, a book that was a biographical study might have a greater potential of reaching a wider audience than a book that was around a more analytical or thematic or conceptual category. So that’s one other appeal of the biography, I think – that it allows you hopefully to write in a freer way, in a looser way; it challenges you as a writer, and it might help you reach a wider audience – although we’ll see whether or not that hope is fulfilled.

Finally, Sean Scalmer, what lessons does Berry’s life and this earlier history of colonial democracy carry for present day debates about political activism and democratic participation?

Well, I would say, first off, although I call the book Democratic Adventurer and although Berry identifies as a democrat across his career, we do need to remember that what he called democracy and what others called democracy in the nineteenth century was still a highly restricted polity, marked by restrictions of race and of gender. So part of what I’m doing in the book is recapturing those exclusions and thinking through the ways in which some of the beneficiaries of that system didn’t necessarily seek to widen the system as much as they might have. So that’s one thing to think about.

We live in a moment where the franchise is relatively wide – but there are still various kinds of restrictions – restrictions of age, in an environment of looming environmental catastrophe, where younger people aren’t enfranchised; and also we have a very, very large number of people living in Australia who aren’t Australian citizens and do not have the right to vote, and yet government policy has an enormous impact on them. And their industrial rights, their political rights, their rights to welfare are highly restricted, and they don’t have the option of parliamentary politics in order to try and influence government policy. So that’s one aspect to think about – a less positive story, I suppose.

The other thing I would suggest would be understanding democracy as creativity, and as self-invention, and re-creation. As I said earlier, I think democracy is best understood not as a set of fixed arrangements or fixed rules, but rather as a project of self-government, in which institutional forms are open to re-imagination and revision, and Berry is exemplary as someone who understood popular government in those terms. So he was someone who, as I said earlier on, who practised and widened … the practice and possibility of free speech; who widened the possibility of the public sphere, not just through his speaking but through his editorship of newspapers and his enactment of arguments for political change; who changed what the institutional or organisational base to politics was by creating a new mass party, and by trying to work with others through that party. He’s someone who tried to change the rules, the constitutional rules that governed the polity, and to move them in a way that allowed for greater popular involvement… So he’s a reminder that when we look at our own democracy, that it’s not something that’s perfected; rather, it’s something that if we’re to be true democrats, that invites the quest for change and the quest for further reform.

Finally, as I mentioned earlier, one of the things that his career discloses is that even with the most creative and determined political leadership, political activists face very many barriers, and restrictions. And those aren’t just restrictions connected with the rules of the parliamentary system and the wider state, but also built into the context of a capitalist economy, in which business has great power to respond to what they see as dangerous reforms by refusing investment and by undertaking a capital strike. And one of the things the book shows is that when a radical government faces a capital strike, it’s in a very difficult position indeed, because as unemployment rises, so naturally people begin to question whether it’s wise to support a government that business does not support. And there’s a turn often to a political party and political leadership that will restore business confidence. So that’s a problem that has bedevilled radicals who’ve tried to use the parliamentary system and social movements since the nineteenth century. Berry’s career doesn’t offer necessarily any solutions to that problem, but it is a reminder of the great challenges that radical activists and social movements face in the quest for change.