Australia’s Earliest European-built Boat?

The Barangaroo Boat, as it has come to be known, was discovered in November 2018 during development works conducted by Sydney Metro. After completing her MA in Cultural Materials Conservation in 2019, Heather Berry took up a job as a maritime conservator, working with Silentworld Foundation to conserve and preserve the Barangaroo Boat. In this article, Heather describes what is involved in this work, which brings together some of her favourite things in life: diving; exploring history; and caring for precious relics of the past.

In 2018, archaeologists excavating for the creation of a rail station at Barangaroo unearthed an unexpected find – the remains of a timber boat. Although now a terrestrial site due to land reclamation, this part of Sydney was waterfront at the time of the Barangaroo Boat’s deposition, and formed the shoreline in front of a shipyard. This vessel was excavated in November 2018 for Sydney Metro by archaeologists Casey & Lowe and Cosmos Archaeology, who undertook archaeological excavations of the craft and surrounding contexts.

The little boat was found to be clinker-built (overlapping hull planking with frames added for reinforcement), its hull hewn from Australian native timbers. At this stage in the archaeological analysis, it is unknown how the boat was used, but it is believed that it is from early 1800s colonial Australia, likely the oldest European-style Australian-built boat ever excavated.

Carefully excavated by specialist archaeologists, the boat’s hull components were painstakingly dismantled, wrapped, and stored in refrigerated containers under the supervision of International Conservation Services, until the conservation phase could begin.

Silentworld Foundation, a not-for-profit organisation with an interest in early Australasian maritime history, was contracted to undertake the conservation phase, working closely with Ian Panter, a specialist in shipwreck conservation, from York Archaeological Trust to oversee the project. As Ian is based in the UK, Silentworld Foundation decided that there should be an Australian-based conservator on the ground. It was decided that it should be an emerging conservator, in order to build capacity of maritime conservators in Australia. At this stage, in October 2019, Irini Malliaros from Silentworld Foundation contacted the University of Melbourne Grimwade Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation to find a recent graduate interested in maritime conservation – and this is where I became involved!

Things became a bit of a whirlwind from here – in mid-October I handed in my Masters thesis (an exciting milestone!), skipped drinks with my classmates and hopped on a plane to Sydney that evening. The next day I headed out to the warehouse where the boat was still tucked tight into its refrigerated containers, and we began unwrapping and cleaning. Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM), maritime archaeologists Kieran Hosty and Dr James Hunter, who were present during the excavation, also contributed their time and considerable expertise to the conservation phase from the very beginning.

So how did I end up here? I did my undergraduate degree at the University of Melbourne in Arts, double majoring in Psychology and Ancient World Studies. This led into an Honours year in Ancient World Studies, which I adored. I took a year off and lived in the Seychelles, diving and surveying corals, then obtained my divemaster qualification and worked at a dive shop. At this stage I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do next. I knew I wanted to incorporate my love of history with my diving, but when I returned to Australia, I was initially at a loose end when it came to finding a way to combine these two passions.

The Cultural Materials Conservation Masters Degree really spoke to me – it would allow me to handle objects and pieces of history, and to care for them was an enchanting prospect. Further research revealed that even my love of diving and the ocean could be incorporated – Australia, as a land girt by sea, has internationally renowned maritime conservators who conserve the artefacts excavated from the many shipwrecks along our coastlines.

So I applied, and was accepted, starting in 2018 along with a cohort that had incredibly diverse interests; my classmates worked on a range of specialisations from paper, performance, and paintings, through to terrestrial archaeological conservation.

I was able to tailor the course toward my own interest in maritime conservation, and as a result was fortunate enough to do an incredibly enriching and eye-opening internship at WA Shipwrecks Museum in Fremantle, WA as part of my studies. When Silentworld Foundation contacted the Grimwade Centre looking for an early career maritime conservator, I was able to take up this unique opportunity.

What started as a casual position assisting with cleaning timbers turned into a full-time contract.

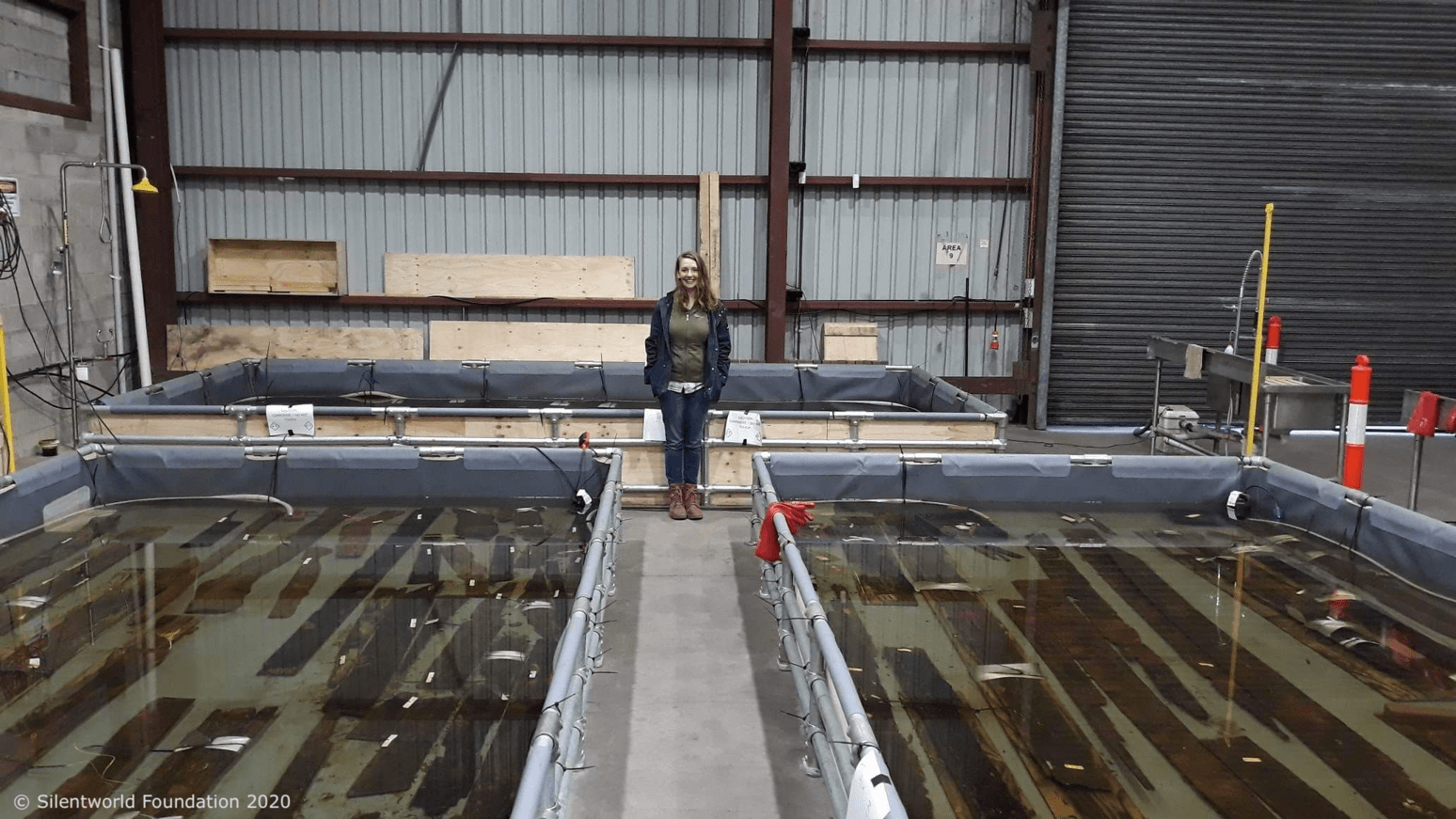

The Barangaroo Boat has been a complex and intricate project. Each timber was methodically removed from the refrigerated containers, unwrapped, photographed, and subsequently cleaned using toothpicks, water streams, dish brushes, and plastic scrapers. Next, the timbers were transferred into tanks of water; although the ship was found in a terrestrial context, its proximity to water meant the timbers were waterlogged, and so must remain wet to prevent shrinking, cracking, and warping.

The next stage was to use a structured light scanner to record each timber, so that they can be modelled into a 3D digital representation of the boat. This stage was presided over by 3D specialist Thomas van Damme from Ubi3D, and it was followed by the lengthy process of removing each timber from the tank, laying it out, and annotating every feature – every fastening hole, grain direction, and saw mark – on the scan of each timber. Annotation and 3D scanning ensures that the construction methods can be studied and other analysis can be undertaken without direct access to the timbers – useful when it is undergoing active conservation (and so may not be accessible to researchers), or once it has been reconstructed.

This leads us to where we are now – teetering on the precipice of active conservation. The next phase is to add ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). As a chelating agent, it will remove iron ions from the timber matrices. This is a really important step; iron can be a food for microbes which in turn produce sulphur, which subsequently can attack timbers up to decades later and cause serious damage to the timbers and boat overall. These issues have been well documented in the Vasa, Batavia, and many other conserved shipwrecks. The EDTA treatment is merely to mitigate this effect, as there is not currently a way known to remove the iron completely.

After EDTA treatment, the timbers will be left to marinate in slowly increasing concentrations of polyethylene glycol (PEG) wax. This second-to-last stage is what allows the boat’s timbers to be removed from water, and able to be on open air display. This conservation process is widely used in the field of shipwreck conservation, and is a well-tested, reliable method, having been used on the Mary Rose, Vasa, and Batavia to name a few.

At present, water molecules are bulking out the cells of the timbers. PEG will displace the water, and hold up and strengthen the cells so that the current shape of the timbers can be maintained. Finally, in order to ‘set’ this stage, all timbers must be freeze-dried in order to remove remaining water molecules in the form of vapour and prevent warping and cracking. The aforementioned EDTA treatment, used to reduce iron, is important at this stage. If a large amount of iron remains, it can interact with PEG in two ways: it can prevent diffusion of the wax into the wood cells, and can cause decay of PEG.

Once any excess wax is removed from the surface, the final stage, reconstruction and display, can commence.

These steps and phases are laid out logically and appear to be set in stone, but there are still plenty of surprises that we look forward to uncovering. In many ways this is an unorthodox boat; its construction methods to the choice of timber species are certainly unusual, and although we do not yet know who built it, and for what purpose, we are looking forward to understanding more.

This truly is a one-of-a-kind boat, and a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to be able to work on it, and preserve it for posterity.

The Barangaroo Boat Project is overseen by Sydney Metro, who in turn have involved the expertise of multiple companies and individuals including: AMBS Ecology & Heritage, Australian National Maritime Museum, Casey & Lowe, Cosmos Archaeology, Silentworld Foundation, Ubi3D, and York Archaeological Trust.

All images (unless otherwise noted) are property of, and used with permission by, Sydney Metro.

Follow the project on Sydney Metro, and Silentworld Foundation’s website, Facebook and Twitter.