Historians Working for Justice at the Waitangi Tribunal

Five History graduates from the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies have ended up working for New Zealand’s Waitangi Tribunal Unit at the Ministry of Justice. The Waitangi Tribunal is one of the key institutions engaged in protecting Māori rights under the 1840 Waitangi Treaty. At a time when the ‘job-readiness’ of Arts graduates has increasingly been called into question, their stories illustrate just how vital historical research skills can be in effecting change in the real world, and in preparing graduates to pursue a meaningful and rewarding career. Current PhD candidate Jonathan Tehusijarana interviewed two of these graduates. Dr Daniel Morrow is a Principal Historian in the Tribunal’s Report Writing team, while Dr Keir Wotherspoon is a Senior Research Analyst in the Research section of the Tribunal.

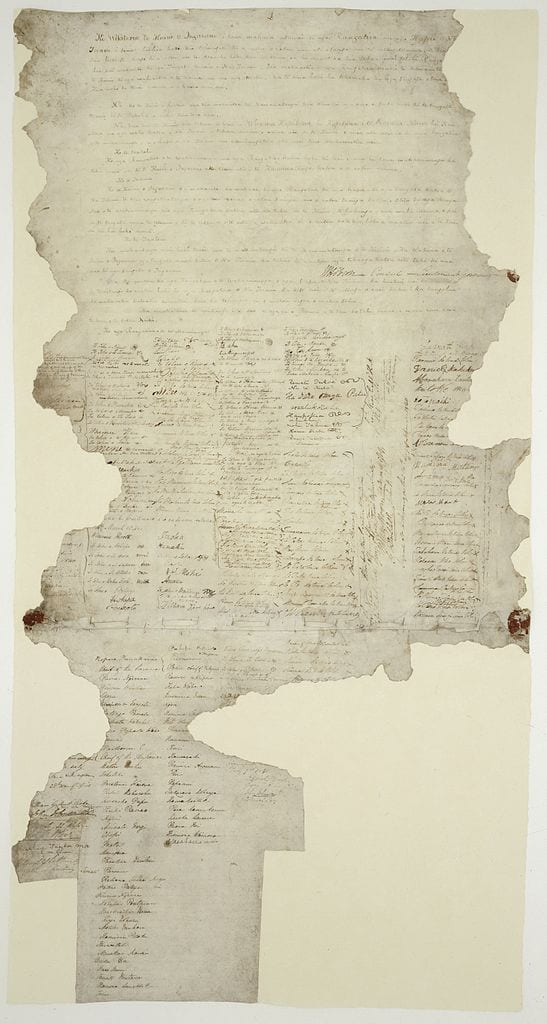

The Waitangi Tribunal was created by the New Zealand government in 1975 in response to ongoing Māori activism. One of the core demands of the Māori protest movement was for a legal mechanism to be put in place for investigating historical violations of the Treaty of Waitangi, signed in 1840 between the British Crown and a collection of Māori rangatira (chiefs). A full description of the Treaty of Waitangi and its central role in the evolution of New Zealand can be found here.

Initially, the Tribunal was not empowered to investigate historical violations of the treaty, and was limited to processing claims that Māori had been prejudiced by contemporary crown actions. This changed in 1985, when the Tribunal gained the power to investigate claims leading all the way back to the signing of the Treaty in 1840. This gave an added historical dimension to the workings of the Tribunal and has made historical expertise even more vital to its work. While their work has at times been contested, there can be no doubt that the Tribunal’s recommendations have played an important role in effecting real change in New Zealand.

What does your job at the Waitangi Tribunal Unit involve, and what was the path that brought you here?

Dan: I received my PhD from SHAPS in 2010. My thesis was titled ‘Melbourne’s West: A Study of People, Place and Community Formation’. This was an area-based study of how local communities were shaped by migration, economic restructuring, and other trends in twentieth-century Australian urban history. After graduating, I was appointed to a fixed-term lectureship in the School of Historical Studies at the University of Otago in New Zealand, where I did research and taught courses in New Zealand and Australian history.

After leaving Otago, I changed tack slightly and took up the position of Curator of Social History at Waikato Museum in Hamilton, New Zealand. After six years coordinating diverse exhibitions and other historical and heritage projects, I was appointed Principal Historian in the Report Writing team at the Waitangi Tribunal Unit, New Zealand Ministry of Justice, in November 2018.

I work with one other Principal Historian in the Report Writing team, and together we manage standards of writing and analysis across the work our team produces. In my time at the Tribunal Unit, I have overseen staff assistance with the drafting of several major reports on historical and contemporary issues, working with the unit’s report-writing team to improve their technical skills and liaising with judiciary and Tribunal members.

Traditionally, report writing has serviced what are known as District Inquiries – these are large inquiries, based on geographic areas, that combine hundreds of mostly historical claims on a wide range of issues: land legislation, alleged political and economic disempowerment, environmental and resource management. The work can be very detailed and requires strong analysis and writing skills. A key part of my role as Principal is to mentor staff to help grow their technical ability as report writers.

We’re still doing plenty of work in the District Inquiry space, but increasingly the Tribunal will be moving toward inquiries on contemporary claims. These may grapple with modern structural issues affecting all Māori, like the national healthcare system, or they may be urgent inquiries in which claimants are contesting an impending or pressuring Crown action or policy. In that case, a concise report needs to be produced in a relatively short window of time. The skills required for this kind of work are slightly different to the district inquiries but, in many ways, complementary. One of the challenges of our role is fostering versatility among the team so staff can work across the various types of inquiries we service.

Keir: I completed my PhD in 2017, after submitting my thesis titled ‘Convergence and Divergence: The Radical Origins of the Network Revolution and its Transformation of the Public Sphere’. My thesis examined how political radicals and cultural rebels in the US grappled with the question of how to make a democratic public sphere in the face of what they saw as a degraded and atomised mass culture. One of the things I wanted to do in my thesis was explore the story of the emerging networked condition that came about through the fusion of countercultural idealism and cybernetics, and try to incorporate this into how we think about the public face of radicalism in the 1960s.

After my PhD, I ended up lecturing and supervising at Masters level for a year at the Centre for Interdisciplinary Methodology at the University of Warwick. I read the anthropologist Christopher Kelty’s work during my time there and became interested in tracing some of the communities and ideas that I had explored in my thesis into the present day.

Somewhere towards the end of a year-long fellowship, I took a group of students to MozFest in London. This is a tech conference that, according to one pithy summary, “explore[s] the intersection of the web with civil society, journalism, public policy, and art” (with a big focus on open source and networked community). It seemed like the perfect way to observe these tech activists I studied in my thesis in their natural environment.

There were sessions on open source tools for citizen journalism, collaborative decision-making software, digital radicalism under authoritarian rule, and one where attendees sat at the feet of Tim Berners-Lee as he outlined his newest scheme for re-democratising the internet. I should have felt enlivened by it all but by this point, I was deep into my ECR season of angst about what I would do once the fellowship had reached its end.

I chanced on a session on the relationship between indigenous knowledge and open source protocols. The two presenters from Hawai’i and Aotearoa brought these ideas back around to the Waitangi Tribunal’s report addressing Māori intellectual property and kaitiakitanga (guardianship). I had worked for the Tribunal’s report writing team after I finished my Honours year in New Zealand, so I felt an instant connection to what they were saying. But more than that, seeing the ripple effect that the Tribunal process had initiated was, at that moment, very exciting. The session was one of those occasions where you catch sight of the important things out there that you could be contributing to. So, I left with the Tribunal on my job radar again.

I should say that although I ended up working in this area, I probably went through that same process of thinking dozens and dozens of times about what kinds of alternative pathways there were to academia. They might not have led anywhere, but I found it was good to keep my mind open as a way of staving off a small part of the post-PhD angst.

My role (Senior Research Analyst/Kaitatari Rangahau Matua) sits within the research section of the Waitangi Tribunal Unit. I support the research needs of an inquiry and the sitting panel. Under the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975, which established the Waitangi Tribunal, any claim made by Māori against the Crown can be investigated by the Tribunal (since 1985 Māori have been able to make claim on issues dating back to 6 February 1840). That investigation has been underway for the past 45 years. Commissioned research to support the investigation of claims has been central to that inquiry process over that period.

How has your historical training helped your work at the Tribunal Unit?

Dan: Having training and professional experience in historical research has been very useful, primarily in having learned to be a close, critical reader of texts. That skill is invaluable here, where I am constantly reviewing colleagues’ written work.

An advantage of history as a background is that in most cases it matters less what topics you have researched in the past than the generic skills you have acquired, which can be applied to a range of analytical and research tasks. The ability to understand and synthesise large volumes of material – legal submissions, legislation, minutes, hearing transcripts – is a skill Tribunal Unit work requires that many historians have acquired, though certainly it’s not exclusive to them.

Keir: A key aspect of the research team’s role is to provide ‘expert evidence’ to sitting Tribunal panels. Research commission topics can range from subjects like nineteenth-century Crown-Māori political engagement to contemporary social housing policy and social inequality.

In practical terms that work involves research into archival and published sources, which results in the production of a technical report. That’s familiar enough territory for history graduates (and there are two other SHAPS history grads in my team, Esther McGill and Timothy Gassin).

But the conclusion of that process for the researcher involves testing that evidence through cross-examination in a public courtroom-like setting, and that has no real analogy in our historical training. Imagine something like a thesis defence (but with fifteen legal counsel and a special judicially led panel as your examiners) and you’ll get close to understanding the process.

Could you describe some highlights of your time working at the Tribunal Unit?

Dan: I’ve had the great privilege of providing service to some of New Zealand’s most esteemed historians, former politicians, kaumatua (Māori elders), business people and others from various spheres of our society who sit on the Tribunal’s inquiry panels, as well as the members of the judiciary who preside over the inquiries.

Probably most though, I’ve enjoyed the camaraderie of working with our team members, sometimes on a tight timeframe, to help the inquiry panels draft reports (and feeling that our work is ultimately contributing to a just outcome).

Keir: I’m in the process of proposing a research program for an inquiry. It’s involved a deep dive into analysing around 100 claims (some of which stretch to 30 pages or more over dozens of issues dating back to the nineteenth century) and then working out a research programme that would adequately and coherently respond to the issues. Consultation with parties is critical in this process, so the proposal is sent to claimants and the Crown for their submission and these in turn are discussed in conference before a presiding judge.

As much as I enjoy research and writing, it can often be singular and lonely work and one of the biggest drags can be that nagging existential thought – who am I writing for? The satisfaction of this process has come from the knowledge that the research is serving a very real need.

There has been some debate recently about the relevance of Arts and Humanities degrees in today’s economy. What place do you think Humanities graduates have in the modern workforce?

Dan: I think humanities graduates are very well equipped to compete in today’s evolving workforce. I’m aware that in Victoria the State Government is taking steps toward Treaty with Indigenous peoples of the region. I imagine such a process would require at least some research into the relationship between Indigenous Victorians and the state over time and that demand for archival historical skills and experience might emerge from that quarter.

With its federal system, Australia has a fairly large and diverse public service, parts of which have for a long time valued history graduates due to their analytical abilities. I don’t see that stopping and if anything, would anticipate this relationship continuing to grow alongside the traditional education and heritage sector pipelines. Tertiary sector jobs are obviously limited, but that’s been known for a long time and every year research graduates seem to be thinking more and more beyond that, which is heartening.

Keir: Everything would fall apart without us.

SHAPS graduates that currently work alongside Dr Morrow and Dr Wotherspoon at the Waitangi Tribunal Unit include Dr Timothy Gassin (PhD 2015) and Esther McGill (MA 2012). Dr Rachel Patrick (MA 2009), who previously worked at the Tribunal Unit, has recently taken up a position at the New Zealand Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care.