Cuckoldry in Early Modern England

Early modern English culture displayed an obsession with women’s infidelity and anxieties around the shame this brought on their husbands. History major Joseph Moorhead explored this topic for the subject A History of Sexualities (HIST30004) in 2020, and was awarded the 2020 Laurie R Gardiner Prize for the best undergraduate essay in early modern British history (1400–1700). This article is a revised version of Joseph’s prize-winning essay.

Horns, horns, horns!

The early modern period ought to be called the ‘age of horn’.

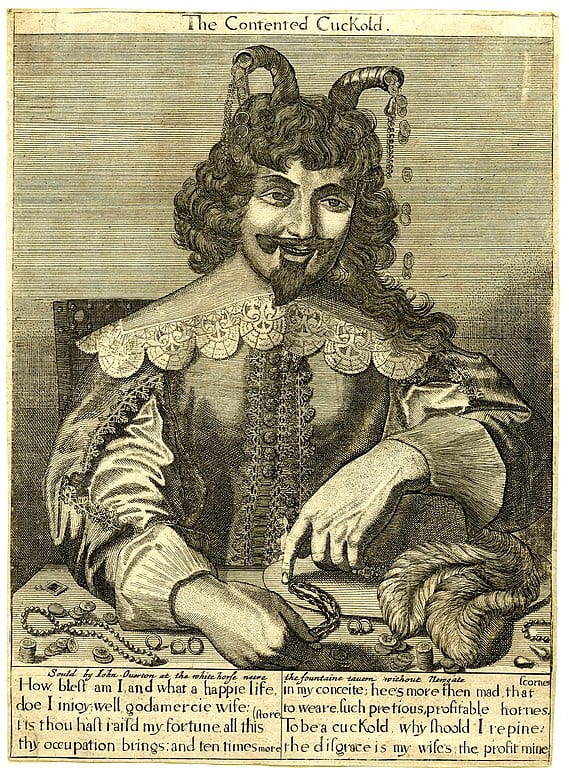

To be ‘horned’ was to have been made a cuckold – a married man rendered shameful and impotent (‘horned’) by an unfaithful wife. A wife’s infidelity would cause her husband’s head to be adorned by a pair of invisible animal horns, the ultimate sign of his cuckoldry. Horns and cuckoldry became ubiquitous in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England as a focus of scornful humour, infecting everything from ballads to Shakespeare.

The horned cuckold was certainly a potent source of levity and target of derision. But cultural fixation on cuckoldry also reflected broader anxieties around gender: to be horned was to achieve a critical failure in masculinity. Horned men were either unable to control or unable to sexually satisfy their wives. Neither situation was enviable.

In recent decades, historians such as Mark Breitenberg and David Turner have elevated cuckoldry anxiety to the level of an early modern crisis of masculinity. This perspective is alluring; it certainly seems as if cuckold humour acted as a pressure release for masculine anxieties, allowing men to negotiate their fears while reasserting the need for female chastity and deference.

But is the suggestion of a ‘crisis’ too extreme, or perhaps too simple? Can we really explain horn humour so easily, or was there more to early modern cuckoldry obsession?

A Crisis of Masculinity?

Horn humour was everywhere in early modern England. Cuckoldry was not a new phenomenon, figuratively or in popular culture, with prominent examples even littered across Geoffrey Chaucer’s fourteenth-century Canterbury Tales. However, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries it became a staple of comic entertainment and, according to the editor of the Post Angel periodical in 1701, “an Injury that cannot be parallell’d upon Earth”. From the ballads that pervaded taverns and streets, to the “prodigious crowds” that flocked each year from 1682 until 1751 to enjoy Edward Ravenscroft’s irreverent production The London Cuckolds, cuckoldry jokes were pervasive, popular, and a reliable source of both hurt and hilarity.

The sharp edge of horn humour focused on the shame a wife’s infidelity brought her husband, whose primacy in the household was a double-edged sword. Men were afforded authority over their wives but, with this authority, came accountability and an expectation of control and chaste behaviour. A women’s infidelity therefore fell squarely on her husband; he was the head, so he must bear the horns. This logic was clearly expressed in a 1708 edition of the British Apollo: “tho’ a Man and his Wife are one Flesh, yet the Husband is the Head, and must consequently wear the Horns”.

The imperative for a husband to suppress his wife’s sexuality also presented another paradox of patriarchal expectation. Women were considered uncontrollably sexual by nature; they were, as sixteenth-century English scholar Robert Burton asserted in The Anatomy of Melancholy, “irregular and prodigious in their lusts … diverse in their affections”. This supposedly rampant sexuality made infidelity almost a guarantee. “Marry a lusty maid”, Burton wrote, “and she will surely graft horns on thy head … all women are slippery, often unfaithful to their husbands”.

For men, cuckoldry anxiety therefore became a product of multiple paradoxes — men should assume primacy over women but they must also bear the horns of their every misdemeanour; men know that women are lascivious and unfaithful but they must nevertheless ensure their absolute chastity. The sixteenth-century French philosopher Michel de Montaigne echoed the threat of these implicit contradictions: “the very Idea we forge unto their chastity is ridiculous”, he warned, “there are fewe amongst us, that feare not more the shame they may have by their wives offences …” For Montaigne, cuckoldry anxiety was therefore “the most vaine and turbulent infirmity that may affect a man’s mind” but it was also an obsession produced by the “rules of life prescribed to the world”.

From one point of view, then, cuckoldry obsession was an over-emphasised response to the contradictions of the early modern patriarchal system, a crisis that reveals the inherent limits and paradoxes of what Montaigne described as the “rules of life”.

But is this view just an overly simplistic explanation of a complex phenomenon?

A Continuum of Cuckoldry

When we look more closely, we find that cuckoldry was a complicated and highly differentiated category. Horns were not created equal; some were small, others large, and the size of a cuckold’s horns modulated the nature and severity of their social transgression. Cuckolds were distinguished in ballads and almanacs through the language of ‘orders’, ‘sorts’ and ‘degrees’. Eight “orders of cuckold” differentiated the “horned ranks” in The Tinker of Turvey, a sixteenth-century parody of The Canterbury Tales. These orders included the contented “winking cuckold”, the jealous “horne-mad cuckold” and the even more severe “cuckold and no cuckold”, which referred to men so fearful of “knobs on their forehead” that they assumed horns regardless of their wife’s fidelity. The last category tapped into a common contemporary criticism of horn-madness: “wee not be lesse Cuckoldes”, Montaigne pondered, “if we lesse feared to be so?”

The Poor Robin satirical almanac of 1699 also produced a continuum of cuckoldry but with a more measured development of degree. The “Loving Cuckold … is best”, the “Patient Cuckold … lives at rest”, while the “Jealous Cuckold [is] double twang’d”, and the “Pimping Cuckold would be hang’d”. Such attempts to classify cuckolds from “best” to “hang’d” reflect a more complicated understanding of cuckoldry than suggested by the encompassing notion of a crisis in masculinity.

Not all horns, however, bellowed an anthem of dishonour; a cuckold could escape disgrace, provided they reacted appropriately. The June 1676 edition of Poor Robin’s Intelligence provided one such example of an honourable response: it chronicled the story of a cuckolded London shoemaker who “handsomely curried [the cuckold-maker’s] hide and sent him packing”, a swift and confident reaction which earned the shoemaker praise for having published neither “his Wife’s faults or his own shame”.

But just as cuckolds could minimise their horns, they could also swell and enlarge them. The most contemptible breed of cuckold was known as the ‘wittol’, a special term intended to extract extra shame from the cuckold who condoned his wife’s infidelity. The contempt reserved for the wittol was well captured by an insult directed at William Dynes in 1609: “go thou cuckoldy slave, thou wittol, thy horns are so great that thou canst scarce get in at thy own doors!” Even the wittol, however, could be powerful; a popular ballad called the Cooper of Norfolk chronicled a wittol who merrily leveraged his wife’s infidelity for his financial advantage. “The Brewer shall pay well for using my Fat,” the wittol happily swore, “farewell to the trade of a Cooper!”

Differentiation between degrees of cuckoldry ultimately interrogated the limits and meanings of male dishonour, so that the potential for both grace and disgrace lurked within a cuckold’s horns. The 1661 cuckoldry treatise Horn Exalted concluded with the same suggestion of complex continuum: horns, they asserted, symbolised “both for honour and disgrace”. This ambivalence clouds the suggestion that cuckoldry obsession constituted a manhood crisis, but it also paves the way for a more measured interpretation: cuckoldry as a mechanism of social catharsis and unification.

Cathartic Cuckoldry: A Brotherhood of Horns

Perhaps the only reliable constant of the cuckold continuum was that cuckoldry was a social leveller: horns sprouted “from the throne to the cottage”. Horn humour commonly invoked this notion of shared male experience to present cuckoldry as an inclusive and bonding condition, a ‘brotherhood’ with distinctly cathartic potential. Shakespeare was particularly fond of this interpretation; he commonly presented cuckoldry as a natural condition of marriage with both comedic and more serious inferences. The hunting song of As You Like It connects horns with the inevitability and commonality of cuckoldry, a message of inclusion enhanced by the communal imperatives of the choric voice:

Take thou no scorn to wear the horn;

It was a crest ere thou wast born:

Thy father’s father wore it,

And thy father bore it:

The horn, the horn, the lusty horn.

In Much Ado About Nothing, bachelor-turned-husband Benedick’s calls of “Get thee a wife! Get thee a wife!” also invite membership to marriage as a fraternity “tipped with horn”. The Clown from All’s Well That Ends Well sings it most plainly: “Your marriage comes by destiny/Your cuckoo sings by kind”.

Suggestions of ‘brotherhood’ and ‘fraternity’ also applied this lighter brand of horn humour outside of literature and performance. The Bull-Feathers Hall Society convened in London every Tuesday and Thursday in the late seventeenth century to make “mirth and merriment” with their “brethren” about cuckoldry; they wore feathers as horns and aimed to make “publick laughter at that which so much troubles others”.

With even more ironic overtones, a seventeenth-century ballad summoned all members of the “Hen-Peck’d Frigate” to “Cuckolds-Point” on the Thames in London, where they would be put to work readying the footpath to “Horn-Fair” for the “pleasure and delight” of their wives and lovers. The ballad attempted to invoke solidarity through the notion of brotherhood, enhanced by its ironic description of cuckolds as “Knights of the Forked Order”, but it also had roots in reality. Horn-Fair was a real annual carnival in Charlton with a reputation for debauchery and Cuckolds-Point was a notorious tourist spot described by Dutch artist William Schellinks in 1661 as a place of great “fun and amusement”.

Horns, then, were laughed at, but they were also laughed with: cuckolds invoked shared experience to bond with other men and exorcise their own anxieties.

This cathartic potential also manifested in local charivari traditions, which combined corrective imperatives with festivity and merriment. Charivari customs varied in character and flavour across England and Europe but most drew on what Martin Ingram describes as a “peculiar mix of the penal and festive” to address anomalous social behaviour, including cuckoldry and other violations of patriarchal authority.

The central element of charivari was typically cacophony: “rough music” produced by pots, pans, bells, fireworks, and discordant instruments that both attracted attention and provided aural humiliation for the intended recipient. Other charivari demonstrations were more elaborate, including extensive use of horn imagery and “skimmington” rides, where the offending party or an effigy was paraded on a horse to be ridiculed by their community.

Humiliation was certainly a goal of charivari; it was ridicule designed to correct bad behaviour. But charivari was often also described with the language of ‘sports’ and ‘games’ conducted ‘in merriment’,and some charivari occurred in tandem with larger holidays and festivities. The essential merriment informing charivari also suggests catharsis rather than crisis: like broader horn humour, rough music was only as rough as it was festive and fun.

Crisis or Catharsis?

Horns, horns, horns. If not a crisis of manhood, horn-madness certainly illuminated fault lines in masculinity. A cuckold’s horns were invisible, but to the early modern English man they must have felt awfully real: an emblem of male impotence and the limits of patriarchal authority. Yet horns and the anxieties they provoked were never truly interpreted in the monolithic sense that ‘crisis’ suggests.

Early modern cuckoldry ultimately operated on a complex continuum, and horns could stand for both honour and disgrace. Even the detested wittol could leverage power from his wife’s infidelity. Within this continuum, horn-madness was more cathartic than catastrophic, even if that catharsis fundamentally relied upon the potential for catastrophe. Men found comfort and solidarity in ironic suggestions of a brotherhood of horns, and the supposed inevitability of horns applied a lighter and more inclusive logic to cuckold comedy.

While cuckoldry certainly provoked terrible masculine anxieties, it also created laughter with as much as laughter at — and, so, horns of catharsis rather than crisis were commonly fixed upon the horn-mad men of early modern England.

Joseph Moorhead completed his BA in 2020 and commenced his Juris Doctor at the Melbourne Law School in 2021. He loves pirates and is especially interested in the intersection between law and history, particularly in the fields of British and Australian history. History was his first love and he plans to return to further study in the future. This article is dedicated to the memory of Professor Laurie Gardiner.