Days of the White King

Before novels such as Game of Thrones, extraordinary tales of kings and conquests could be illustrated from the pages of history. When Maximilian I ruled the Holy Roman Empire, Europe was made up of small principalities and kings strode about like pieces on a chess board playing out territorial wars. The cannons they trained on each other breathed dragon fire; aristocratic hostages were used for political bargaining, betrothals and betrayals were all part of their strategies for war and diplomatic games.

Emperor Maximilian I (1459–1519) of the house of Hapsburg was the King of the Germans and ruled the Holy Roman Empire, jointly with his father from around 1483 and alone from 1508 until his death. Maximilian’s days were marked by artillery fire: ‘at two years of age the infant Maximilian was shut up in Vienna besieged by his uncle. The first memories of the child thus cradled in the lap of war with cannon shots for lullabies, were of the hardships and perils of a soldier.’[1] He was a knight (of the Order of the Golden Fleece) and also an exceptional patron of the arts, an innovator who left an astounding body of printed works which tell us about his times.

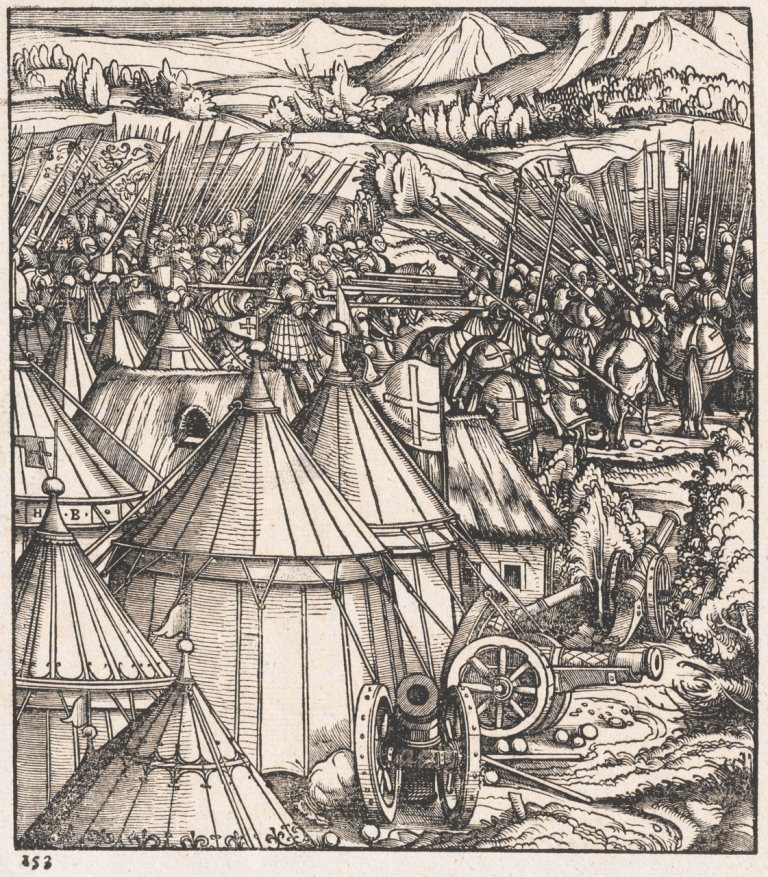

One of these works is his saga Der Weisskunig (The White King), which is the allegorical name given to Maximilian the hero, and is an autobiographical epic. The work contains 251 illustrations by Hans Burkgmair and other notable German artists including Leonhard Beck. It is arranged in three parts: the history of Maximilian’s parents, Frederick III and Eleanor of Portugal; Maximilian’s birth and education; and the chronicle of his military campaigns. Other kings in the narrative are identified by colours or symbols. Owing to Maximilian’s death, The White King project which commenced in 1515 was not printed until 1775. Examples from the series may be found in the Baillieu Library Print Collection.

The alliance of three kings against the King of Fish is a depiction of the League of Cambrai which was formed during the Italian wars. Here termed as the King with Three Crowns, is Pope Julius II, the Blue King (Louis XII), the Black King (Ferdinand II of Aragon) and the White King (Maximilian I) against the King of Fish who represents the republic of Venice.[2] The League of Cambrai, like many of the alliances made in Maximilian’s time, was based on interests that could dissolve or turn hostile at any moment. So that in The White King allies in one image may be at war in another.

Maximilian’s son and heir, Philip the Handsome would become the King of Castile through his marriage to Joanna of Castile. Philip’s unexpected death meant that it would be his son Charles V who would succeed Maximilian as the Holy Roman Emperor, and also rule the Spanish Empire. Philip and Joanna had six children and Maximilian arranged for an auspicious double marriage between two of them: Mary of Hapsburg to Louis II of Hungary and Ferdinand I to Anne of Bohemia and Hungary. This is encapsulated by the book written for him by Johannes Cuspinianus, Congress and meeting of Emperor Maximilian and the three kings of Hungary, Bohemia, Hungary and Poland in Vienna (1515) held in the Rare Book Collection.[3]

Despite the scenes of military might in The White King, it was through marriage that Maximilian and his descendants created the most powerful alliances and conquests. His printed legacy ensures that the incredible stories about his deeds and his legend are remembered, and explain why Maximilian has also become known as the paper king.[4]

For more about Maximilian I and the University of Melbourne see ‘Mad Max and the Renaissance’ in Cultural Treasures Festival Papers 2012, University of Melbourne Library, 2014.

Kerrianne Stone (Special Collections Curatorial Assistant (Prints))

[1] Paul Van Dyke, Renascence portraits, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1905, p. 264.

[2] Larry Silver, ‘Caesar Ludens: Emperor Maximilian I and the waning Middle Ages’ in Cultural Visions: Essays in the History of Culture, edited by Penny Schine Gold and Benjamin C. Sax, Amsterdam, 2000, p. 194.

[3] Congressus ac conventus Caesaris Max. et trium regum Hungariae Bohemiae, et Poloniae in Vienna Pannoniae mense Julio anno 1515 facti brevis description, Wien: J. Singrienius, 1515.

[4] See Larry Silver ‘The “Papier-Kaiser” Burgkmair, Augsburg and the image of the Emperor’ in Emperor Maximilian I and the age of Dürer, edited by Eva Michel and Maria Luise Sternath, Albertina, c. 2012.

Categories

- Uncategorised

- Prints

- Special Collections

Leave a Reply