Mrs Pankhurst, her daughter and the Prime Minister: the suffragettes and the Great War

The recently released movie Suffragette has introduced a new audience to the extraordinary history of the movement for women’s suffrage in the United Kingdom, in particular its militant wing represented by Emmeline Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). The movie ends before the declaration of the First World War, but the war was to split the movement and its famous protagonists, in particular the Pankhurst family.

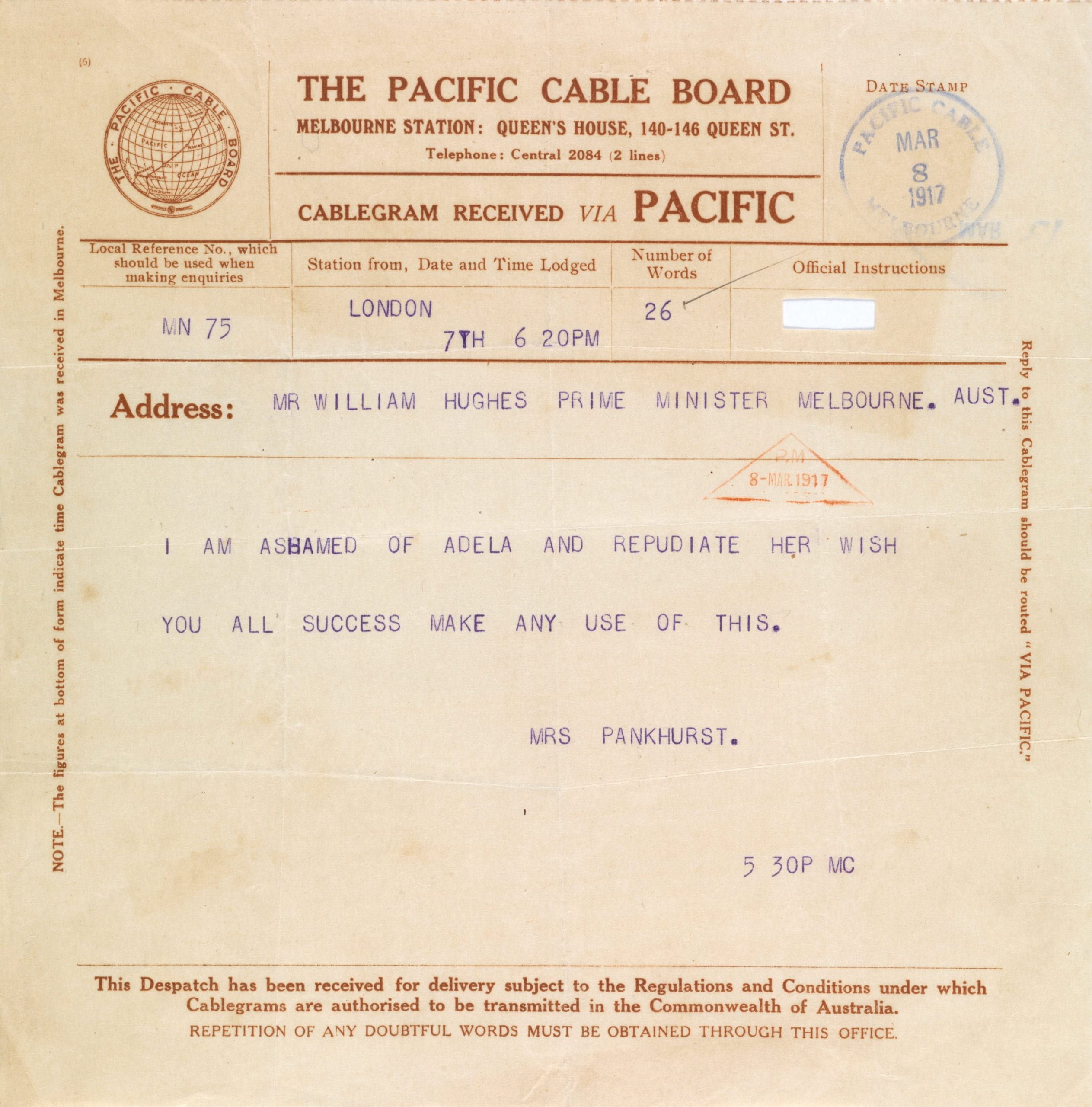

The depth of this rift is revealed in a recently discovered telegram from Emmeline Pankhurst to Australia’s Prime Minister Billy Hughes, dated 8 March 1917. In this telegram, Emmeline Pankhurst denounces her famous daughter Adela for her opposition to the war and her activities in the anti-conscription campaigns in Australia.

The telegram is powerful new evidence of the intensely political nature of the suffrage movement and to the surprising political realignments sparked by the war. It also points to international connections between the suffragettes and the unionism and socialism movements.

The UK women’s suffrage movement reverberated in the United States, Australia and elsewhere.

In Australia, non-Indigenous women had received the vote and the right to stand in federal elections by 1902. In Victoria, women were only granted the vote in 1908 and the right to stand as candidates in 1917. Vida Goldstein was Victoria’s leading suffragist, who began her political career helping her mother collect signatures on the huge Woman Suffrage Petition, now housed at the Public Records Office of Victoria. The WSPU invited her to the UK in 1911.

Goldstein’s public activity was not confined to the right to vote; she campaigned for compulsory arbitration and equal pay and equal rights for women workers, against the White Australia policy and against capitalism. In 1915 she founded, along with Cecilia John, the Women’s Peace Army which called for the abolition of conscription and militarism and equal rights for women with the motto “we war against war”.

Adela Pankhurst left England due to health problems in part bought on by her repeated imprisonment in conditions graphically depicted in the movie, but also due to an estrangement with her mother and sister Christabel over the direction of the WSPU. She arrived in Melbourne in April 1914, immediately joining Goldstein’s suffrage organisation the Women’s Political Association and, once it was formed, the Women’s Peace Army.

In 1917, Pankhurst joined and became an organiser for Tom Mann’s Victorian Socialist Party, a large and influential socialist organisation. She began a career of public speaking against the war and particularly against Hughes’ plans to introduce conscription. This stand raised her mother’s ire. Emmeline Pankhurst supported the war and had come to an agreement with the British government to cease campaigning for suffrage. She even helped recruit young men for the war, a position that distinguished her from much of the suffrage movement.

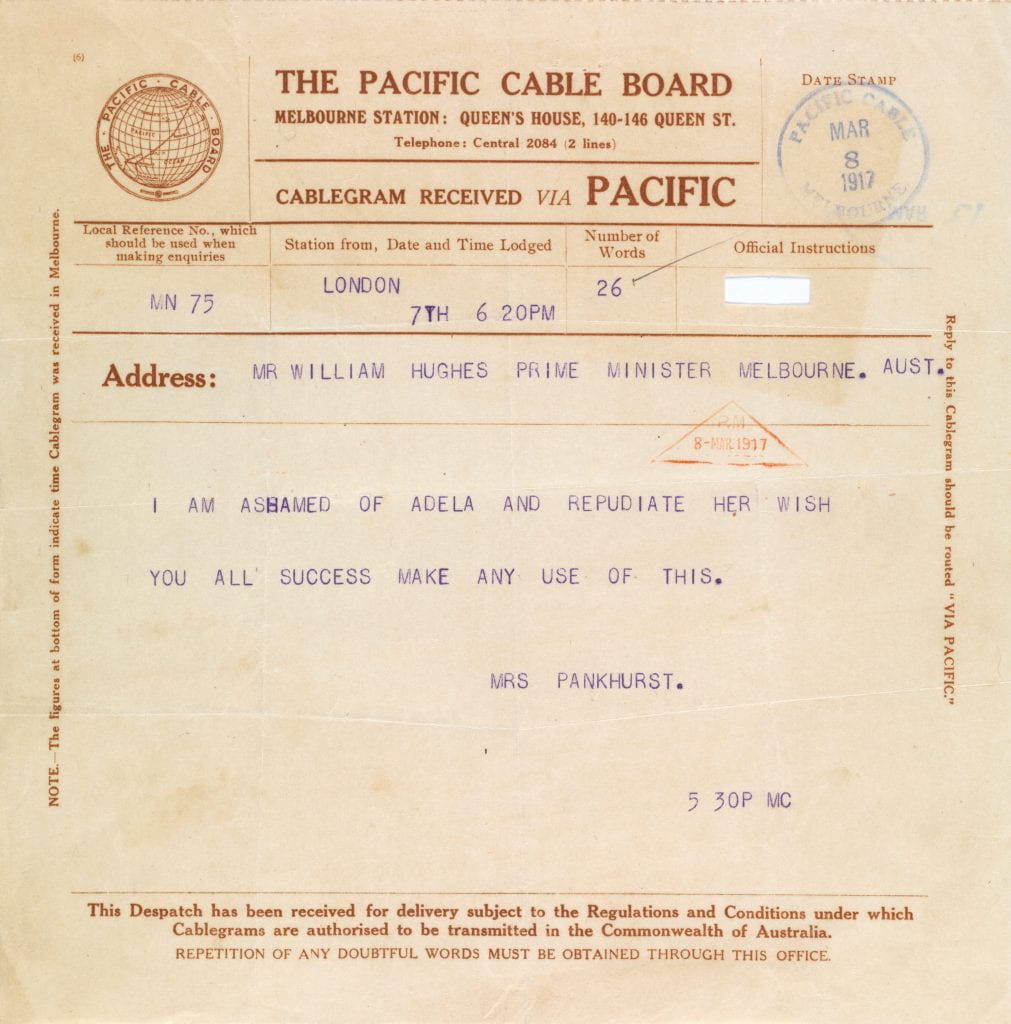

Much like her mother, Adela Pankhurst’s oratorical skill was renowned and she was invited to speak to anti-conscription meetings throughout the country, as shown by these minutes (right) of the Bendigo Anti-Conscription Campaign Committee. Women were a central part of the anti-conscription campaigns, which advocated a (successful) no vote in two plebiscites undertaken by the Hughes government, in October 1916 and December 1917.

Pankhurst and Goldstein became household names. So did other women activists such as Lizzie Ahern, Bella Lavender (nee Guerin, the first woman to graduate from the University of Melbourne), and Jennie Baines, another British suffragette who had moved to Australia after repeated imprisonment.

In late 1917, Baines and Pankhurst led large women’s marches in Melbourne against war profiteering and increased price rises. Press reports said the marches descended into riots. Both women were arrested and Pankhurst served four months after refusing Hughes’ offer of release on the condition that she not speak in public again.

After the war, Pankhurst and her husband, Tom Walsh, leader of the Seamen’s Union, were founding members of the Australian Communist Party. Both moved politically to the right and by 1928 Pankhurst had founded the Australian Women’s Guild of Empire, a group that advocated cooperation rather than industrial action during the Depression.

Pankhurst’s final protest was a hunger strike in 1942. She had been interned in the furore following the attack on Pearl Harbour because of her very public support for Japan.

The threads connecting the suffrage movement, the unions and the socialist organisations through the years leading up to and during the First World War are complex. But they tell of a fascinating period in which women activists were at the forefront of political agitation and change. Alongside this activity, it is also important to recognise the powerful political debates about theory and strategy that guided these activists in many different directions.

The Suffragette movie is an interesting glimpse into one of these strands. The records these women have left behind tell a history even more profound and multifaceted and thus also worth knowing.

You can listen to an interview with archivist Katie Wood on Radio National Breakfast about the telegram here. A further interview on Radio National’s Life Matters, with Katie Wood and La Trobe’s Associate Professor Dr Claire Wright is available here.

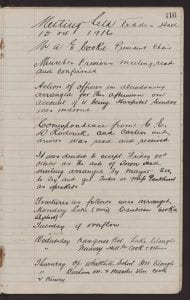

The telegram from Emmeline Pankhurst to Billy Hughes can be found in the papers of Percival Edgar Deane. Deane was appointed Hughes’ Private Secretary in November 1916, a post he retained until he was appointed Secretary of the Prime Minister’s Department 1921-1929. His papers are a fascinating insight into the early years of the Australian public service. They also add a new dimension to our understanding of Billy Hughes. The collection contains correspondence from Hughes and documents relating to the Australian delegation to the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919.

The highlights from this collection will be on display in the forthcoming exhibition, Somewhere in France. This exhibition will explore how the experience of Australians on the Western front during WWI shaped new ways of imagining France. Encounters with the language, food and culture challenged and modified the perceptions and attitudes of the young Australian soldiers, shown though diaries, letters, postcards, images and ephemera from the collections of the University of Melbourne Archives.

The exhibition opens on March 10 2016 in the Noel Shaw Gallery at the Baillieu Library.

Related collections at the University of Melbourne Archives

Suffrage:

Women’s Christian Temperance Union

Australian Women’s National League

Anti-conscription campaign:

Victorian Trades Hall Council – the relevant minutes have now been digitised and are available through our online catalogue.

Bendigo Anti-Conscription Committee – the relevant minutes have now been digitised and are available through our online catalogue.

Creswick Anti-Conscription Committee – the relevant minutes have now been digitised and are available through our online catalogue.

World War One:

Somewhere in France exhibition, opening March 10 2016, Baillieu Library

Other collections of interest:

It was an excellent movie, which encouraged me to read Emmeline’s book, ‘My own story’, written in 1914 and published just as the inter-imperialist war was breaking out. Adela’s move to the far Right is just as interesting as her initial embrace of communism. He grandmother, Emmeline, was an amazing woman who made huge sacrifices for the cause of votes for women. It interests me how many of the tactics deployed so early in the struggle, such as heckling and disrupting politicians’ meetings, writing graffiti on public builidngs, engaging the support of celebrities and violence against property (but not against people) continued through the C20th.

How fabulous. I love seeing the real telegram, and all in favour of more coverage of these fascinating debates. But I don’t think it’s newly discovered. The rift with Mrs Pankhurst and the wording of her message to Hughes disowning Adela are often quoted eg in Bomford’s biography of Vida. It’s such a ruthless message, isn’t it? Imagine being Adela (or Sylvia, for that matter). You can hear Billy Hughes cackle from here.

It looks like an interesting and useful book, so thanks for pointing it out. I checked the reference and it’s given as the Rose Scott papers from the State Library of NSW. I wonder how to explain this as the original is definitely from the Deane papers at UMA.

In Judith Wright’s article Feminists, Food and the Fair Price in Labour History No 48 1985-6, Hughes is quoted from correspondence to Keith Murdoch as complaining in late 1917; “Adela Pankhurst is making herself a damned nuisance and I really don’t know what to do with the little devil…” So perhaps he wasn’t cackling so much after the cost of living riots!

It was a pretty hysterical time, and the peace movements weren’t very peaceful. I just want to acknowledge the Archives for digitising all those important documents. Thank you! Now going to plunge into the Trades Hall minutes…