Mirror mirror on the wall, whose was the most influential encyclopaedia of them all: the story of Diderot’s radical Encylopédie of sciences, arts and technical crafts

The heroic task of bringing together and documenting the vast canon of human knowledge in written form, has been accomplished by a select number of individuals and publishing houses over time. One of the most extraordinary of these achievements was the publication between 1751 and 1772 of 27 large folio-sized volumes of the Encyclopédie, ou: dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, a complete edition of which is housed in the Baillieu Library’s Rare Books Collection.[i]

Financed by subscription and issued in serial form (including 10 volumes of illustrated plates), this enormous compilation of more than 70,000 articles was at once a technical manual, a highly political and philosophical work, and an entrancing written and visual commentary on 18th century French society. Such was its popularity and influence that by 1789, 25,000 copies were in circulation in several editions across Europe.

Financed by subscription and issued in serial form (including 10 volumes of illustrated plates), this enormous compilation of more than 70,000 articles was at once a technical manual, a highly political and philosophical work, and an entrancing written and visual commentary on 18th century French society. Such was its popularity and influence that by 1789, 25,000 copies were in circulation in several editions across Europe.

The Encyclopédie was edited by the philosopher and writer Denis Diderot (1713-1784) and, for the first eight years of its conception, in collaboration with the mathematician Jean d’Alembert (1717-1783). The two had been commissioned to translate the two-volume Chambers’ Cyclopaedia, or Universal Dictionary of the Arts and Sciences (1728) into French but were greatly dissatisfied with the scope of the English compendium, and urged their publishers to embark upon a much improved and comprehensive French production.[ii]

More than a mere factual encyclopaedia, the work was in itself an instrument of the Enlightenment, promoting in its text and pictures the power of reason and the individual over that of divine order and centralised control. Diderot was motivated to share human knowledge and ideas freely with an emerging reading public, as a means for inspiring technological improvements, and to promote economic and political progress.[iii]

More than a mere factual encyclopaedia, the work was in itself an instrument of the Enlightenment, promoting in its text and pictures the power of reason and the individual over that of divine order and centralised control. Diderot was motivated to share human knowledge and ideas freely with an emerging reading public, as a means for inspiring technological improvements, and to promote economic and political progress.[iii]

At first the French officials tolerated the sometimes radical views espoused in the text but as new volumes were released the Encyclopédie became increasingly controversial: the publication licence was withdrawn in 1757, and the work was added to the Catholic Church’s list of banned books. During this period the editors moved production over the border to Switzerland, focusing their outward attention on the engraved plates, whilst burying the more revolutionary opinions deep in the text or by using irony as a means for masking the censor’s eye.

Mirror making

Mirror making

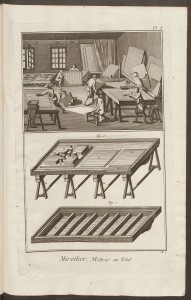

The Encyclopédie included a strong emphasis on the manual arts and technology, the processes and tools of many of which had been hitherto kept secret to protect individual cartels. One such example was the craft of mirror making, the techniques of which are illustrated in Volume 8 of the plates in a series of charmingly rendered engravings.[iv]

Mirror making has a fascinating history and in late 17th century France mirrors had become a luxury import, with the vogue for reflecting hallways and rooms attaining craze proportions amongst the aristocracy.[v] Mirror manufacture was the sole monopoly of the Venetian state, with the exact process remaining highly classified information, the release of which was punishable by death and the imprisonment of family. By report mirror making was:

‘a law unto itself. It had its own rules and customs, and a separate language too, handed down not only from father to son but from master to apprentice…Theirs was a closed community, with every man, woman and child knowing his place within the walls’.[vi]

The French Finance Minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-1683), introduced extensive internal reforms to promote French manufacturing in many closed industries, and lured a few renegade Venetian mirror makers to Paris to divulge their secrets. In response the Venetian authorities despatched emissaries who it is thought succeeded in poisoning some of the dissenters, though not before the French workers had obtained sufficient information to replicate the manufacturing process.

Using the newfound knowledge the French mirror making industry made further technical advances, and by the time of the publication of the Encyclopédie mirrors were ‘sparkling’ in a multiplicity of roles in fashionable society. Mirrors were embroidered into clothes, worn as jewellery, incorporated in hair accessories and makeup, decorated furniture, and were used in mantelpieces and other architectural devices to lighten rooms. The vogue for reflection demanded larger, full length mirrors, in which the viewer, dressed in the style of Madame de Pompadour (herself a subscriber to Diderot’s multi-volume work) could view her bouffant wig and dress in their entirety.

Using the newfound knowledge the French mirror making industry made further technical advances, and by the time of the publication of the Encyclopédie mirrors were ‘sparkling’ in a multiplicity of roles in fashionable society. Mirrors were embroidered into clothes, worn as jewellery, incorporated in hair accessories and makeup, decorated furniture, and were used in mantelpieces and other architectural devices to lighten rooms. The vogue for reflection demanded larger, full length mirrors, in which the viewer, dressed in the style of Madame de Pompadour (herself a subscriber to Diderot’s multi-volume work) could view her bouffant wig and dress in their entirety.

Mirrors, and their reflected realities, also appear in the world of books and literature, in the Brothers’ Grimm tale Snow White, Shakespeare’s Richard III, Tennyson’s The Lady of Shallot, and Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, and feature in many paintings and artworks, such as the medieval The Lady & the Unicorn tapestries and Van Eyck’s the Arnofoldi Marriage[vii]. Thanks to Diderot and the contributors to the Encyclopédie we also have a wonderfully evocative insight into the mirror making mind-set and manufacture of pre-Revolutionary France.

My thanks are extended to University of Melbourne lecturer Emeritus Professor Peter McPhee and history student, April Hamill, for their inspiration for this post.

Susan Thomas, Rare Books Curator

Endnotes

[i] Diderot, Denis. (ed) Encyclopédie, ou : dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers. 3rd ed. Livourne: de l’Imprimerie des Éditeurs, 1770-1776.

[ii] Pannabecker, John. ‘Diderot, the Mechanical Arts, and the Encyclopédie: In Search of the Heritage of Technology Education’, Journal of technology education, Vol. 6, no. 1, 1994, http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/JTE/jte-v6n1/pannabecker.jte-v6n1.html

[iii] Pannabecker, John, Ibid.

[iv] Diderot, Denis (ed). Recueil de planches, sur les sciences, les arts libéraux, et les arts méchaniques, avec leur explication… 3rd ed. Livourne: De l’imprimerie des éditeurs, 1771-1778.

[v] Prendergast, Mark. Mirror, mirror: a history of the human love affair with reflection. New York: Basic Books, c2003, pp.148-149.

[vi] Prendergast, Mark, Ibid, p. 153

[vii] Mullen. John. ‘Ten of the best mirrors in literature’, The Guardian, 30 October 2010. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/oct/30/john-mullan-mirrors-literature-review

Bibliography and further reading

Bates, Brian with John Cleese. The human face. London : BBC Worldwide, 2001.

Diderot, Denis and Jean d’Alembert (eds). Encyclopédie, ou : dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers. 3rd ed. Livourne : de l’Imprimerie des Éditeurs, 1770-1776.

Diderot, Denis (ed). Recueil de planches, sur les sciences, les arts libéraux, et les arts méchaniques, avec leur explication… 3rd ed. Livourne : De l’Imprimerie des Éditeurs, 1771-1778.

Donato, Clorinda and Robert M. Maniquis (eds). The Encyclopédie and the Age of Revolution. Boston : G.K. Hall, 1992.

‘Encyclopédie’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Encyclop%C3%A9die. Accessed 5 August 2016.

Miller, Jonathan. On reflection. London : National Gallery Publications, 1998.

Mullen. John. ‘Ten of the best mirrors in literature’, The Guardian, 30 October 2010. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/oct/30/john-mullan-mirrors-literature-review. Accessed 5 August 2016.

Pannabecker, John. ‘Diderot, the Mechanical Arts, and the Encyclopédie : In Search of the Heritage of Technology Education’, Journal of technology education, Vol. 6, no. 1, 1994, http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/JTE/jte-v6n1/pannabecker.jte-v6n1.html. Accessed 5 August 2016.

Prendergast, Mark. Mirror, mirror: a history of the human love affair with reflection. New York : Basic Books, c2003.

Select essays from the Encyclopedy : being the most curious, entertaining, and instructive parts of that very extensive work, written by Mallet, Diderot, d’Alembert, and others. London : Samuel Leacroft, 1772.

Leave a Reply