Some Fascinating Early Woodcuts of Women from Boccaccio’s De Claris Mulieribus

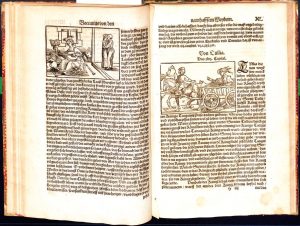

The Rare Books Collection holds a German edition of this text, printed in 1541, which is full of intricate (and occasionally incredibly gruesome) woodcut illustrations of women, courtesy of notable German printer, Heinrich Stayner.[1]. De Claris Mulieribus is a crucial piece in the history of Western literature, and of Renaissance history, being one of the first texts to appear with women as its primary focus.

De Claris is comprised of 106 short biographies of ‘famous women’. This work acts as a feminine counter to a similar project undertaken by a compatriot and close friend of Boccaccio’s, Petrarch, whose De Viris Illustribus is a collection of 36 biographies of famous men through history. The subjects of Boccaccio’s work are drawn from a number of sources, including religious texts, as is the case with Eve, the first woman to appear in the book; through Greek and Roman myths, where a large number of the subjects including Circe, Medusa and Isis originally appeared; to real life heroines, including Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt, and Sappho, the Greek poet.

It is this praise of women of antiquity that marks this book as a pivotal moment in Renaissance literature. The familiarity Boccaccio displays with Livy, Ovid and Pliny, among other ancient writers is demonstrative of the ways in which they were embraced and drawn upon as a source for humanist philosophers. Indeed, as Virginia Brown, in the Introduction to her 2003 translation writes, Boccaccio here ‘provides a striking foretaste of ideas that would later find clearer expression in the Renaissance….such as the view that it was appropriate for gifted women to seek and acquire fame for their contributions to art, literature, and the active life of public affairs.’[4]

Over the course of its life, the University’s copy of De Claris has been witness to these changing attitudes towards women. As previously mentioned, the text contains a short biography of Sappho, the Greek poet. Sappho is best known for her poems about love and women, and through history, both her character and her writing has been subject to an array of both praise and condemnation. Her poetry, rediscovered in the medieval and later period, led to speculation regarding her sexuality, with critics chastising her for her apparent homosexuality.[5]

Perhaps this is why, in the University’s copy, the pages relating to Sappho have been torn out? Not removed carefully, but ripped, leaving a jagged shard of paper behind. It is easy to imagine this page devoted to Sappho, who was adopted during the Modernist period (by Djuna Barnes) as a ‘patron saint of lesbians’, being torn out at some point in the book’s life, during one of the many periods when patriarchal and religious views pertaining to women and homosexuality have erred on the side of condemnation.

De Claris Mulieribus is an incredibly important work, not only in the history of Western literature, but as an artefact and embodiment of Renaissance thought. This relatively progressive text paved the way for other early works depicting women, such as those by Geoffrey Chaucer (1343-1400) and Christine de Pizan (1364-1430).[6] De Claris stands as a crucial piece in the history of women in literature, and indeed in the history of women and feminism, literally embodying the way attitudes towards women have changed over time.

Jaxon Waterhouse

Research Assistant, Rare Book Detectives Project

Museums and Collections Projects Program

Endnotes

[1] Giovanni Boccaccio, Ein Schoene Cronica oder Hystoribuch... Augsburg: durch Stayner, Anno M.D.XXXI [1541]

[2 Virginia Brown, On Famous Women, xv-xvi.

[3] Brown, xviii.

[4] Brown, xiv-xv.

[5] Reynolds, THE Sappho Companion, 295.

[6] See: Christine di Pizan The Book of the City of Ladies, Geoffrey Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales.

Leave a Reply