Taking on the Universe

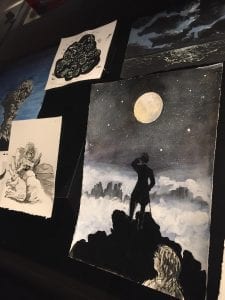

Special Collections Blogger Anastasia Vassiliadis interviews Kristin Headlam, the artist behind “The Universe Looks Down”, a series of etchings currently on display in the Noel Shaw Gallery.

Can you tell me a little bit about yourself? Where were you born, what was your childhood like? I was born in Launceston and spent the first 18 years of my life there, before coming to the University of Melbourne to do a Bachelor of Arts. I’m an only child but, unlike many only children, I believe my childhood was essentially very happy. Apart from a patch quite early on, I wasn’t particularly lonely. Mainly I liked to draw and read and play the piano. At school I hated sport, and was a buck-toothed dag, but could earn brownie points by drawing horses for my classmates. I also had an uncle who was an artist. He was enormously encouraging, and was a great help in showing me how to draw those horses, amongst other helpful drawing techniques.

How did the idea come about to commission a series of etchings for the university? Was it your idea or did the university approach you?

My partner, Chris Wallace-Crabbe, wrote a 67-page zany narrative poem called The Universe Looks Down, which he completed, after 14 years of tinkering, in about 2002 to 2003. Full of characters going about their different quests in life, it’s a seductively visual poem, which is what drew me in: almost immediately I could imagine the kind of images I would make to accompany it. As it turned out, what I ended up producing was utterly different from my early imaginings and watercolours were eventually ditched in favour of etchings.

At a University event I found myself talking to Philip Kent, the then-University Librarian. I told him that I was thinking of making an artist’s book based on Chris’s poem, and he looked very interested and said that the Library commissioned things like that: with Chris’s 50-something-year connection with the University, and his papers being in the University Archives, it would be an appropriate addition. I was very excited by this, so I went away and worked on drawings for over a year, before coming back with a proposal, which was accepted. By that time I had begun to feel that the poem was a great deal more complicated than I had at first thought, and I’d now drifted towards the drawing/etching option.

How long did it take to create the art that is displayed in the exhibition? Were you given a timeline to work with? Was it produced under pressure or whenever inspiration struck?

It’s all become a bit vague, but all up I think it took around six years to produce the suite of etchings. It was suggested that I should finish it much more quickly than I did, but it wouldn’t allow itself to be rushed! I’m not very good at working under time pressure, and I detest deadlines, but I do like to beaver away steadily till something’s done, that I can be sure is as satisfactory as possible.

What was it about the poem that inspired you to create your collection? Was it the imagery, a particular phrase, the tone?

Firstly, it was the beautiful lines: “Like videos the islands drifted past”; “up there against the sun/Or cloud-tumbled, he can feel as free/As Icarus or eponymous Apollo”; “if a lion could speak we wouldn’t understand it”, all appealed to the romantic in me. Secondly, there is the all-seeing observer, Milena, (“Milena is a scribe”) who can see all the characters going about their quests, but has no power to influence events. I began to see her as someone akin to myself, an artist, whose whole raison d’être is to see, but who, like Milena, is tied to a study or studio. She is the one who brackets all these adventurous quest seekers within her ordinary daily life of computer screens, tea and television. Without her the poem would be too airy, not grounded enough.

What is your favourite piece from the collection? Why?

I like different ones for different reasons, but perhaps my favourite is the one of Milena with a fox and a hedgehog, looking down at herself looking at a blank canvas, while another self runs away into the sunlight outside. It came from the line, “She tries again, noticing that she thinks…But where did she get this very notion of thinking?”

The fox and the hedgehog come from Isaiah Berlin’s essay of 1953 which refers to a fragment from the Ancient Greek poet Archilochus (“a fox knows many things, but a hedgehog one important thing”). It divides writers and thinkers into one or the other category. Chris and I used to jokingly say that pretty much described us. Chris seems totally fox-like with an interest in everything, and so does The Universe Looks Down. For someone like myself, more of the hedgehog persuasion, the poem presents a huge challenge to try and see the world from the fox’s viewpoint. In the end though, while Chris is mainly fox, he does have a hedgehog-like focus, through which he views the many things of the world. That focus is words.

Can you describe your process when creating your artwork. Do you have a specific approach or do you approach each piece in a different way?

I always start with drawings. It’s thinking with the hand. Chris’s poem is so rich with imagery, some of it sublime and transcendent, some of it very slangy and jokey, so I had to give some sense of how all that resonated with me. There was a huge number of drawings for each image as I tried to clarify what I wanted. Most of those sketches never made it to the final etching phase.

Can you describe the process of etching, what it involves, for those who do not know? Does this process vary at all for different works, or is it always the same?

Etching is a bit like glorified drawing. Its principle is to draw with a needle through an acid-resisting coating (bitumen paint in this case) painted over a zinc or copper plate. When you’ve made your drawing you put the plate in a bath of acid, and the acid attacks (or etches) the lines you’ve drawn. After the plate has been in the acid long enough for the acid to bite the lines deeply enough to hold the ink, you take it out. Then you clean off the bitumen paint with turpentine and wipe ink over the plate. The ink will have gone into the acid-bitten lines of the drawing. When you place a piece of paper over the plate and run them through a press the ink will be transferred onto the paper, and so you have a mirror image of your drawing. The first “pull” of a print is almost always disappointing: you usually have to go back and work on the plate with more bitumen, then more scratching, more acid, and scraping. Usually the artist decides how many prints she is going to make – this is known as the edition. The Universe Looks Down is a very small edition – only six sets, due to the large number of images, and also some time constraints.

In this series I also needed to make a lot of smudgy, watery-looking shadows and tints. The process for making this is called aquatint, and it’s also obtained with acid. Here you cover the plate with a porous ground of even texture (here, powdered resin), which can be fine or coarse. Anything you don’t want etched you stop out with varnish, then the plate goes into the acid until the lightest grey is obtained. The process is repeated until the blacks are etched, the length of exposure to the acid regulating the depth of the tones. Or you can paint acid directly onto the resin-covered plate, which is quite hard to control, but gives a beautiful watercolour-like cloudy softness— this is called spit bite aquatint, and I’ve used it a lot in these prints.

Are you satisfied with your completed artworks, or do you find there’s always something you want to alter, or keep working with? Is it hard to know when a work is finished?

There are always things that I’m never satisfied with, but the work itself seems to dictate when it’s had enough. As I worked on it, I felt that this poem could have generated an almost infinite number of visual responses, but I arrived at a point where I could see that anything further would be superfluous, and I reluctantly had to admit that it was done.

The exhibition includes your sketchbooks and some of your preliminary drawings. Do you always sketch your work or plan it beforehand?

Never as much as with this series! I had to try and visualise the images in the context of each other, and also how I might approach them as etchings. In the earlier phase of this project I didn’t think nearly hard enough about the technical difficulties of turning them into etchings. This was probably good in a way, because we had to really push the etching process to do things that were hard for it, but facing those challenges was all part of the excitement of using the medium.

Apart from etching do you practise any other forms of art? How did you get into etching?

Mostly I’ve been a painter, mainly in oils, but also in watercolour. Apart from a tiny bit at art school I’ve never really done etching, so for all the etching and lithography I’ve done I’ve worked with a master printer. Etching is really a spin-off from drawing, but you’re making multiples. To me it seems more serious than straight drawing, and has a somewhat different look and surface. It’s a fascinating process, and working with a master printer makes it collaborative. This can be a really interesting way to work. For this series I worked in Canberra with John Loane, with whom I’d made prints a number of times before.

How much does your mood affect the way you approach art?

That’s really hard to say. It probably does affect my approach much more than I know. I can be very reluctant to go into the studio if I’m not feeling full of the joys of spring, but I often do go in there anyway, and sometimes just being in the studio can lift my spirits. Or the reverse!

When creating your art, do you work with an idea in mind, or just see how something turns out?

I usually have something in mind, even if it’s not much.

What is it like working with an idea/poem written by your life partner, Professor Chris Wallace-Crabbe? Is this the first time you’ve been inspired by one of his poems?

We always thought it would be good to do something together, but it never really gelled. I never think it’s really satisfactory to simply illustrate a poem – I feel that the work of art must run parallel to the writing, rather than just illustrate the idea. However, after the idea of working on The Universe Looks Down took hold of me, I tried a little practice run working on a series Chris had written called The Domestic Sublime, which were small poems about ordinary things like saucers, making beds, garlic, hair, coat hangers. There I felt it was ok to simply illustrate. It was fun, so I felt more prepared for taking on the Universe!

You stated in an interview that you couldn’t understand the poem when you first read it, and that by drawing it you were hoping to find the meaning of it. Have you succeeded? What do you think the poem is about?

I’d been a bit misled by thinking that because there were characters and a narrative, the poem was about them. It wasn’t. It turns out the poem is really about everything! I’d expected it to have more plot. Instead, the allegorical characters form a kind of structural framework for Chris to roam over the vast range of his interests, from ordinary daily life to mythic, historical and scientific. He says:

Could there be a destiny of mountains

Or something tragic happening to a gene?

This really appealed to me in my search for a way to talk about everything in a single body of work. It was a way of being able to put, say, volcanoes alongside someone making a cup of tea, and a medieval knight with a businessman, and have it all sitting under one umbrella. The poem also enabled me to use simple almost New Yorker-style drawings next to crazy, detailed, surreal images and for them all to be conceptually linked. For another artist this might feel perfectly natural, but for me it was a struggle. But once I’d begun to understand that the characters were just their actions the whole thing began to move along.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

No, I think I’m done!

The Universe Looks Down exhibition will be displayed in the Noel Shaw Gallery of the Baillieu Library until 17 February 2019.

Leave a Reply