The Spirit of England in Australia: Alan Bell’s Nightly Broadcasts

By Harshini Goonetilleke

“Lately, I have been strenuously ramming down Australian throats Britain’s efforts and burden – which swell impressively when you are so many thousand miles away.”[1] Alan Bell was indeed very far away from the wintery English landscape that he called home. May 1942 saw Bell make his way to the other side of the world on secondment to Melbourne radio station 3DB. The well-known Fleet Street journalist, who had made a name for himself through his work at the London Daily Mail and the BBC was now striving to serve his country in Australia, conveying England’s plight to her people in the Dominion.

From Monday to Friday, Bell delivered a series of ten minute talks that addressed both Australia’s involvement in the war and the desperate situation that the English faced against the Germans on the home front.[2] Although Bell was sympathetic to the threat that Australians faced from the Japanese in the Pacific, his broadcasts held a deep bias towards the British effort in Europe, arguing that the defeat of Hitler was paramount.

Bell’s journey to Australia was a fascinating one that I stumbled across when pouring through an extensive collection of his broadcasts held at the University of Melbourne Archives. Interwoven throughout his propagandist discourse lay clues to a larger, intriguing story that made me question why Bell’s life had not been previously studied. Instead, it appeared that his contribution to the British war effort had been almost entirely forgotten, except for a brief mention in Bridget Griffen-Foley’s ground-breaking radio history Changing Stations, in which she describes Bell as an “early chum” who spoke inspirationally about the English spirit.[3] I felt deeply drawn to unearthing both how and why an established English journalist was seconded to Australia, particularly when taking into account his remarkable success at home.

Bell’s first Australian broadcast was entitled “Winston Churchill” and aired on 16 May 1942.[4] This broadcast was one that I continuously referred to in my research, as it revealed Bell’s fascinating and somewhat fervent admiration of the Prime Minister. He had interviewed and spoken with Churchill on several occasions, and had in fact worked side by side with the man himself in the short-lived newspaper, The British Gazette. While this may not seem all that remarkable for a journalist, Bell’s connections to Churchill became infinitely more intriguing when informed that Bell came to Australia “on Winston Churchill’s request”.[5] This could not, however, be substantiated using only the broadcasts and as such, left a significant hole in my research. Consequently, I started to hunt for any information I could find about Alan Bell, contacting the BBC archives in Caversham, the Churchill Archives in Cambridge and the newspapers that Bell had worked for during his time in England. Ultimately, it would be in Melbourne, and at the University itself that I found the breakthrough I needed for my research, and it was given to me by two people who came to know Bell during his time in Australia.

Dr Howard Goldenberg and Associate Professor Christopher Cordner of the University of Melbourne were both closely connected to Alan Bell throughout his years in Australia. When Dr Goldenberg was introduced to Bell, he was, “an aged man with beautiful elocution”, a description that aligns well with the poetic broadcasts Bell gave from 1942-1944.[6] Professor Corder (whose father, Donald Corder introduced Dr. Goldenberg to Bell) also described Bell as a highly articulate man of sharp wit who clearly prided England above all else.[7] These two interviews were invaluable for my research as they not only provided a first-hand description of the man that Bell was, but both Dr Goldenberg and Professor Cordner were able to confirm that Bell had in fact been “Churchill’s man” in Australia. In addition to this immense discovery, Professor Cordner provided me with access to Bell’s personal collection which he had in his possession. From this, my findings about Bell grew exponentially.

The brown cardboard box that sheltered Bell’s personal collection contained a glimpse into an infinitely fascinating life. Within the collection were a number of articles that Bell had written throughout his career, from his first job as an eighteen year old journalist at the Cambridge Daily News to his broadcasting in Melbourne.[8] It also held a letter that demonstrated his links to Harold Harmsworth, the First Viscount Rothermere and founder of the London Daily Mail. From this letter, I was able to draw links between Bell and media magnate Sir Keith Murdoch, who not only had personal connections to the Harmsworth family, but was also owner of the Melbourne Herald, and in turn, radio 3DB where Bell worked in Melbourne.

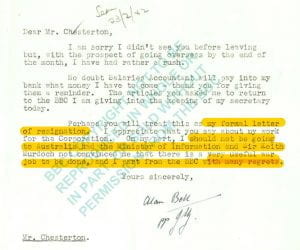

When these findings were interwoven with critical information from within the BBC archives, it became increasingly apparent that Bell was called upon specifically by the British government to perform an important duty for England in Australia. In a telegram from Bell, sent on 20 February 1942, he stated that “I should not be going to Australia had the Minister of Information and Sir Keith Murdoch not convinced me that there is a very useful war job to be done”, underscoring the official nature and urgency of his work in the Dominion.[9] This becomes more apparent when the Minister of Information to whom Bell refers is revealed to be Brendan Bracken, a close personal friend of Winston Churchill, cementing Churchill’s links to Bell’s secondment.[10]

The Prime Minister’s decision to send Bell to Australia was not one to be regretted as Bell’s broadcasts were notably popular among Australians. This is not to say that Bell did not receive negative reactions. He had, on one occasion been accused of spreading “anti-Australian sentiments” and the question of whether he should be “transport[ed] back to England” was discussed in the Australian House of Representatives in September 1943.[11] However, statistics recorded by Bell show that he was listened to and well liked throughout the country. He had a “47 per cent regular audience” in South Australia, and his nightly broadcast was the “sixth most popular feature in the Melbourne area.”[12] When Bell signed off for the last time on 14 September 1944, his colleague at the Herald described the immense “avalanche of letters” that were addressed to Bell expressing their appreciation.[13]

This is by far the most perplexing aspect of Bell’s life. Why, if he was so popular during his time in Australia, has his story been left out of the nation’s radio histories? Other histories of Australia could also benefit from Bell’s story, as it informs our understanding of the “Britishness” of Australians in the 1940s, as well as Britain’s propaganda efforts in their Dominion. Furthermore, it raises questions of how Australians balanced their need to defend their own country with that of protecting England. It seems that the further we unpack the broadcaster’s time in Australia, the more opportunity we gain to widen our knowledge of how both England and Australia sought to navigate the trials of the Second World War. By looking at this time period through a more personal lens, we are given a unique insight into this particular chapter of Australian history, demonstrating that ultimately, Alan Bell’s story is one worth telling.

Harshini Goonetilleke is a former History honours student at the University of Melbourne. For her thesis, Harshini wrote on radio broadcaster Alan Bell, exploring his work in both England and Australia as a propagandist for the British government. This blog post is a direct product of her thesis, The Forgotten Broadcaster: Alan Bell and the Spirit of England.

References

[1] Alan Bell, “Letter to Ryan,” October 12, 1942, BBC Written Archives Centre in Caversham.

[2] Alan Bell, Night In Night Out (Melbourne: Edgar H. Baillie, 1943), 4.

[3] Bridget Griffen-Foley, Changing Stations: The Story of Australian Commercial Radio (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2009), 366.

[4] Alan Bell, “Winston Churchill” (May 16, 1942).

[5] Alan Bell, “Alan Bell, University of Melbourne Archives,” February 22, 2017, http://minerva-access.unimelb.edu.au/handle/11343/125149.

[6] Howard Goldenberg, In conversation with Howard Goldenberg, July 31, 2018.

[7] Christopher Cordner, In Conversation with Associate Professor Christopher Cordner., August 2, 2018.

[8] “From Newspaper to Navy,” The Cambridge Daily News, March 31, 1917.

[9] “Letter from Alan Bell to Mr. Chesterton,” February 20, 1942, BBC Written Archives Centre in Caversham.

[10] “BBC Internal Circulating Memo,” January 8, 1942, BBC Written Archives Centre in Caversham.

[11] “Question of the Day,” September 28, 1943, Alan Bell Personal Collection, Courtesy of Chris Cordner.

[12] Alan Bell, “Letter to Randall,” April 10, 1943, BBC Written Archives Centre in Caversham.

[13] A.H Chisholm, “Broadcaster and His Book,” The Herald, September 23, 1944.

Categories

Leave a Reply