Insurance records are not exciting

By Catherine De Luca

This is not a particularly controversial statement if the first conference for the History capstone subject at the University of Melbourne in 2018 is anything to go by. David Goodman was introducing the Archival History stream, one of four options for students, and made a point of telling us that the University of Melbourne Archives have a large collection of insurance records. I could practically hear the sound of eyes rolling and glazing over. After all, insurance records are for economic historians, right? Not many students in that room had any interest in economic history. This is not where I reveal that I have such an interest, though it is as valid a form of history as any.

This is where I reveal that I saw a challenge. As a hopeful historian-to-be I am aware of the challenges that researchers face when engaging with the public. The investment we have in our topics is not always reflected in the audiences we hope to reach. We must adjust and learn how best to communicate our findings to them. This is especially true for anyone working with archival records, particularly documents that cannot be easily displayed in a visually interesting manner. If the mere mention of insurance records bored a room full of future historians, then what would the general public think? If I could find a way to make insurance interesting to a room of people who rolled their eyes at the very idea of it then I could make anything interesting. Or, more realistically, I would at least be better prepared for future challenges.

If I was to trick my cohort into finding insurance interesting despite their previous response then I knew I should turn to what would interest them, a social element. This made life insurance an obvious focus. After settling on the 19th century, a matter of personal preference, I searched through the records of the Victoria Insurance Co., National Insurance Company and National Mutual Life Association of Australia, the Mutual Assurance Society of Victoria, and some records of the Bright family. Most of the records I found were precisely what I was trying to avoid. Premiums, annual reports, and ledgers required data analysis which might put off a general audience. However, this was not time wasted but time used to refine my purpose. Each document that did not suit my project gave me another sign towards what would.

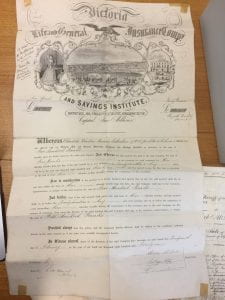

Then I struck gold. It would be disingenuous to say I had no direction before finding the life insurance policy of Charlotte Wilbraham, but one clause in the document solidified it. “This policy will be void if the life assured die by her own hands, by the hands of justice, by duelling, or by suicide.” Death by duelling caught not only my attention but also the attention of every person who heard me mention it. Here was the key to success, using the mundane to reflect on the eye-catching. Most people I spoke to were entirely unaware that duelling ever occurred in Australia, and certainly none thought it would be reflected in insurance records. My final project paired death by duelling with suicide and explored how life insurance companies engaged with these topics in 19th century Australia and what this revealed about attitudes towards these acts.

I wish I could say that following this discovery a wealth of evidence from the Archives became known to me and that it was used throughout my final work, but unfortunately this was not the case. If I ever expand upon the project then I would utilise the data overlooked before, but Wilbraham’s life insurance policy was the only Archives record in the final product. However, this is not the point.

The point is that hidden in insurance records was a story of interest to a student of history more inclined towards social and cultural studies. The point is that my friends, family, and classmates were interested in the final result, and amusingly most acted as though they were interested despite themselves. They were interested in this thing they were so sure should not be interesting. “Why would you think to look there?” was a common question. The very fact that they asked was the answer. The very fact that they asked is the reason researchers need to look in places they think aren’t for them, places that are for other kinds of researchers. The truth is that no field has sole claim to any archival records.

The lesson I learned last year has, to the amusement of my classmates, continued to benefit me. This semester we were tasked with finding items in the University of Melbourne Archives relating to ‘Australia and the Asia Pacific’, and a few different boxes were pulled out to help inspire us. The lone box no-one showed any interest in was the business records of a shipping and general insurance company and, hoping to repeat the successes of last year, I was drawn to it. Lo and behold, contained within shipping correspondence was a story of stowaways and opium smuggling. Shipping correspondence should not be exciting, except it is.

Insurance records should not be exciting, except they are.

Catherine is an honours student at the University of Melbourne, who is working on her thesis on the entertainment and play of children in the Ballarat region from the mid-19th century to the early 20th century. This blog post is a product of her research project for Making History HIST30060 at the University of Melbourne.

Categories

Leave a Reply