Microcosm of a global disaster

By Margaret Mary Sheehan

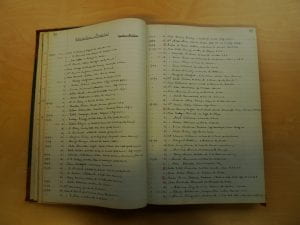

In the pages of the ‘Influenza Temporary Hospital Staff Register’, held by the University of Melbourne Archives, is evidence of the Spanish influenza pandemic that wrought havoc across the world between 1918 and 1920. Bound in red leather and unprepossessing in appearance, this journal was created by the Victorian Branch of the Australian Red Cross Society and contains lists of volunteers who offered their services during the first wave of the virus in Melbourne that started in January 1919. Two more waves or recrudescence swept across Victoria in the following eight months with a devastating effect on the State’s population. More than 3,500 people died in Victoria, a terrible loss after the horrifying war losses.

The journal’s function was administrative and was organised geographically by the volunteers’ hospital location. Thirty-four emergency hospitals (the Register describes them as ‘temporary hospitals’) were created throughout the metropolitan area to manage the critically ill who overwhelmed the health care system during the pandemic. Schools delayed opening after the summer break, and many were converted into emergency hospitals. Also converted were drill halls, kindergartens, army base hospitals, as well as the (Royal) Exhibition Building. Yet buildings were comparatively more easily found than experienced staff as many nurses had yet to return from the war, resulting in a dire shortage of qualified carers. Calls for volunteers went out, and in late January a Red Cross worker began diligently listing names in the ‘Influenza Temporary Hospital Staff’ Register.

The Register recorded those who volunteered over a period of 10 weeks, the first entry being on 25 January 1919 and the final on 11 April 1919, the greatest number offering help in February during the first onslaught of the disease.[1] But what was the purpose of the Register? Was a letter of notification sent to the emergency facility where the volunteer was posted? Were volunteers tracked? Was there more than one Register? Whilst these are seemingly unanswerable questions, we can know that this Register was created by one individual, for the handwriting remains constant. This nameless person had the task of receiving offers of help; listing the date of registering; their level of experience, if relevant; hospital placement; and ultimately preserving this record of volunteers.

More than 670 community members were registered: all were women, mainly offering to nurse and care for the ill, although some volunteered to cook, work in laundries, or act as ward-maids. Little more than 80 were registered trained nurses, accredited by the professional body the Victorian Trained Nurses Association, and not quite a third were members of the Voluntary Aid Detachment VADs. Generally these VADs were young upper or middle class women of ‘independent means’ who would have presented with first aid training and home nursing certificates awarded by St John’s Ambulance.[2] Another smaller percentage (about 50) were described as ‘partly trained’. The majority (337) had no formal training and were simply keen to help in a time of community crisis.

The stress or difficulties of volunteering are also reflected in the Register in a perfunctory manner, for the word ‘left’ is neatly recorded against some names, occasionally in red ink. Many volunteers were young girls (about 550 were described as ‘Miss’) who had never seen anyone critically ill, let alone watched them die, and were required to care for many delirious and distressing cases. Perhaps it is unsurprising that more than 70 left without explanation. The Register also records those who did not survive, such as Annie Prince who died on 1st March 1919, after caring for patients in the Exhibition Building’s emergency hospital.[3] Another, Daisy Carr, died on 14 April, also after caring for influenza patients in the Exhibition Building.[4]

The Red Cross ‘Influenza Temporary Hospital Staff’ Register offers an important glimpse into the human cost of an event that remains Australia’s worst natural disaster in terms of lives lost. It also provides a microcosm of the Melbourne community’s response, and generosity of its female members.

Illustrations

- Hospital beds in the Great Hall during the Spanish influenza pandemic, 1919. MM 103429, Museums Victoria Collections

- Influenza Temporary Hospital Staff Register, UMA 2016.0074.00002

[1] Australian Red Cross Society, Victorian Division, ‘Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) and Field Force Personnel Records’, Influenza Temporary Hospital Staff Register, UMA 2016.0074, pages 13 & 54

[2] Melanie Oppenheimer. 2014. The Power of Humanity : 100 Years of Australian Red Cross 1914-2014. Harper Collins Australia., page 31

[3] Influenza Temporary Hospital Staff Register, ibid., page 32; Weekly Times, 15 March 1919, page 38

[4] Ibid., page 1; Geelong Advertiser, 19 April 1919, page 7

Leave a Reply