Searching for ‘reality’ in art online

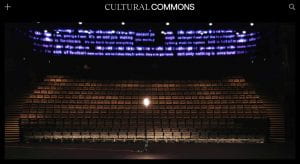

Alone on the stage, the ghost light shines to the empty auditorium. The ghost light is a feature of the theatre, rooted, like so much tradition, in lore and superstition. ‘Some say the ghost light is used to scare away ghosts, but more often the light is used to appease ghosts,’ writes the Melbourne Theatre Company. ‘During the COVID-19 pandemic, theatres around the world have placed ghost lights on their empty stages. For now, these shining beacons symbolise the art form’s survival.’

It perhaps befitting that I do not visit the Southbank Theatre in the flesh, but remotely, and noticeably alone in the cavernous space. I visit via a virtual tour found on the University of Melbourne’s Cultural Commons website. The virtual tour (such as this compilation by TimeOut, or Concrete Playground) is an increasingly common phenomenon in the art world which allows patrons to interact with art spaces online, at any time. In light of the COVID-19 pandemic while museums around the world are physically closed, virtual tours are not only a novelty, but a necessary bridge to what can no longer be experienced in person.

Yet what does the virtual tour offer us in pursuit of an ‘authentic’ experience of art?

You may have come across virtual museum scapes while scrolling though social media, in journalism, or while on museum websites. The virtual experience, while varying from museum to museum, is most often an uncanny process of entering full screen to travel through eerily empty rooms, up staircases—and on occasion accidentally ricochet into the rafters—in extreme high definition. It’s Google street view, but for your artistic institution of choice.

The analogy to street view is no coincidence either. One of the first proponents of the modern interactive tour was the Google Art Project (now Google Arts and Culture) in 2011, captured using similar technology to their panoramic streetscapes. Virtual tours are not the only form of accessing art online of course: you can find almost any artwork or image online these days, even by lesser known artists, and usually in very high definition. Many smaller collections, like the University of Melbourne’s own Special Collections, often offer comprehensive catalogues to view online.

But the virtual experience is different to online catalogues insofar as it provides an opportunity to capture something beyond the artwork itself. The technology does not just document or offer access to artworks as singular objects, rather it adds that essential component of art appreciation: art within context.

How we appreciate an artwork is so wholly dependent on context as to be almost laughable: from the type of frame, where on the wall a painting is hung, the room’s colour, type of museum, or even the city in which an artwork is held creates the narrative and value associations of the work. Context is such a proponent to artistic experience to be the backbone of such Post-Modern practice as Minimalism or relational aesthetics.

For example, when hordes of people visit the Mona Lisa year after year, they do so not just for the artwork itself, but for the manifest authenticity of the original work hung in the Salle des États, behind the great stone edifice of the museum, and in the romantic, foreign city. To search the image would provide a much clearer, even more intimate experience to viewing the painting in the Louvre—but it is hardly the point.

Ironically though, the Mona Lisa’s very Italian origins makes an architype of the Florentine Renaissance, and its modern association with France is only the product of time. In fact, much of the art we see in galleries was not designed to be there: devotional paintings were for churches, portraits for family or private homes, not to mention the complex historical and cultural origins of non-Western art practice. This is all to say that context changes constantly, and the museum space—far from being a blank slate, or the natural place of origin for artwork—is honeycombed with meaning. Furthermore, the kind of virtual tours that get the most publicity on websites like TimeOut do so because of their association with the celebrity museums of the international art word—such as the MET, the Uffizi etc. As such, while the virtual tour is an opportunity to reinstate context in an online world already filled with images, it still situates the high-class institutional museum as the natural precursor to the full artistic experience. To say that we are immune this museum mythologising online is naïve—and the virtual tour is testament to that.

As the virtual art world shifts and changes there will certainly be criticism levelled at what is shown and what is silenced through art online, but the virtual tour now remains the closest thing to capturing the full theatrical (a word open for interpretation) museum experience. Like so many things now, we must be grateful for what we have. Virtual tours were created to replicate the reality of visiting cultural spaces, but today they remain the only eerie acknowledgment of these once bustling spaces. Like the ghost light as a symbol of absence, the virtual tour has come full circle to represent what once was and is no longer, but also what we can hope will come again someday soon.

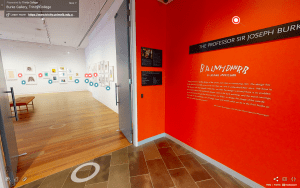

There are a range of virtual experiences on the University’s Cultural Commons Experience page, including Balnhdhurr – A Lasting Impression at Trinity College’s Burke gallery and the Southbank Theatre virtual tour as seen in this post.

Bianca Arthur-Hull

Special Collections Blogger

References and further reading

“The Ghost Light,” Melbourne Theatre Company, accessed 18th July 2020.

Cameron, F. and Kenderdine, S. editors. Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage : A Critical Discourse, MIT Press, 2007.

Dziekan, V. Beyond the Museum Walls: Situating Art in Virtual Space (Polemic Overlay and Three Movements), FibreCulture Journal: internet theory criticism research, vol. 0, no.7, 2005. 1-19.

Singh, N. “Leveraging the Virtual and the Real.” Arts Management and Technology Laboratory, October 6 2011.

Sylaiou, S., et al. “Exploring the relationship between presence and enjoyment in a virtual museum.” International Journal of Human-computer Studies, vol. 63, no.5, May 2010, 243-253.

Leave a Reply