Ulimaroa: a name of curious origin on early maps of Australia

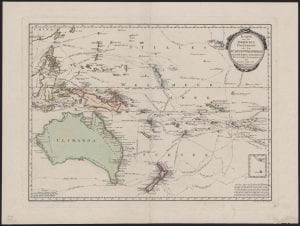

This map, titled Karte von der Inselwelt Polynesien oder dem fünften Welttheile: nach Djurberg und Roberts, or Map of the islands of Polynesia or the fifth part of the world: after Djurberg and Roberts is a 1795 map by Austrian cartographer Franz Johann Joseph von Reilly in the University’s rare and historical map collection.

The source of this map is somewhat difficult to pin point. From 1789 to 1806 von Reilly published his Theatre of the Five parts of the world according to and for use with Anton Friedrich Biisching’s great description of the earth (translated title), yet despite its name, the atlas only catalogued some 800 maps of Europe leaving out much of the rest of the world. [1.] Rather, this map likely came from van Reilly’s 1794-1796 Grosser deutscher Atlas (Great German Atlas),—some examples of which can be found online—and which was the first complete Austrian world atlas.[2.]

The map is notable for several reasons. It traces the routes of various European explorers, such as Ferdinand Mallegan, Pedro Fernandes de Queirós, James Cook and Abel Tasman. ‘In order to see the direction in which they sailed, small arrows which point in the direction of their travel have been attached to the points of their journey. Roggewein’s, Tasman’s and Mendanna’s second journey is only accurately known as far as it is shown on the map,’ [3.] states part of the text in the bottom right hand corner. The map also shows some obvious inaccuracies—Tasmania is connected to the mainland of Australia, whereas Papua New Guinea is split in two. The most noticeable curiosity though, is the name given to Australia: Ulimaroa.

Ulimaroa was first used as a name for Australia by Swedish cartographer Daniel Djurberg. In 1776 he wrote:

The world is divided into 5 main parts: 1. Europe, 2. Asia, 3. Africa, which makes up one large island, 4. America, which makes up the other island, 5. Polynesia, which includes all the large and small islands which cannot be joined to any of the previous four continents and includes, among others, the large island Ulimaroa, which in old geographies is known as New Holland. [4.]

Djurberg believed Ulimaroa to be the New Zealand Māori name for Australia, meaning “big red land”[5.] a belief that he justified in 1801: ‘You find in the account of the famous English sailor Cook’s journeys that when he was on the northern coast of New Zealand, he asked the inhabitants there if they knew any other country, to which they replied that to the north-west of their home, a quite large land was located, which they named Ulimaroa.’ [6.]

More recent scholarship on this origin story suggests that not only was Djurberg wrong in believing the Māori were referring to Australia here, but the name Ulimaroa is also somewhat of a misnomer, and almost certainly did not translate to “big red land.” It is more likely that the island to which the Māori people were referring was New Caledonia or an island in Fiji, and a name more accurately transcribed as Rimaora, not Ulimaroa. [7.]

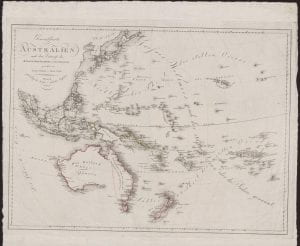

An 1805 map of Polynesia in the university collections by cartographer Franz Swoboda, also printed in Vienna, amends a number of the cartographical inaccuracies in von Reilly’s earlier version, and displays three different names for the region: General map of Australia in the top left corner, and New Holland and Ulimaroa on the continent. Despite its misplaced origin and other alternative (and eventually universal) names for the continent, the name Ulimaroa appeared on Austrian maps of Australia right up until 1819.[8.]

Bianca Arthur-Hull

Special Collections blogger

Footnotes

[1.] Dörflinger, J. “The First Austrian World Atlases: Schrämbl and Reilly.” Imago Mundi, vol. 33, 1981, pp. 65–71.

[2.] Dörflinger, J.,1981, pp. 65–71.

[3.] Translation by E. Devlin via personal correspondence.

[4.] Tent, J, and Geraghty, P. “Where in the World Is Ulimaroa? Or, How a Pacific Island Became the Australian Continent.” The Journal of Pacific History, vol. 47, no. 1, 2012, pp. 1–20. (p.4.)

[5.] Tent, J, and Geraghty, P., 2012, pp. 1–20. (p.9)

[6.] Tent, J, and Geraghty, P., 2012, pp. 1–20. (p.5)

[7.] Tent, J, and Geraghty, P., 2012, pp. 1–20 (p.14)

[8.] Tent, J, and Geraghty, P. 2012, pp. 1–20 (p. 5)

Categories

Leave a Reply