Deflowering Karri Country: settler-colonial seductions in the Commercial Travellers’ Association collection

Simon Farley is a writer, theatremaker and PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne’s School of Historical and Philosophical Studies. They are researching settler Australian attitudes towards non-native animals from the 1820s to the present.

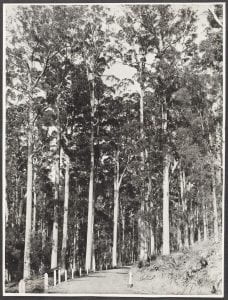

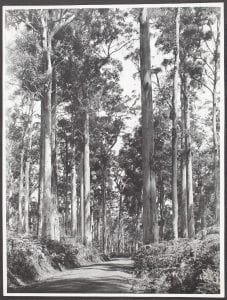

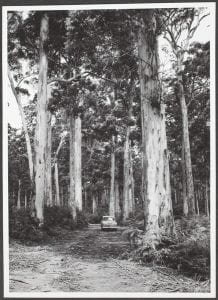

The karri is a tree of gargantuan proportions. This species of eucalypt can live for up to three hundred years, growing above sixty or even seventy metres in height.[1] The straight, towering trunks of a karri forest dwarf any human who walks among them. Karri grow only in high-rainfall areas of southwestern Australia.[2] The karri forests on Noongar country, south of Perth, were one of the few heavily wooded parts of the continent when British colonisation began.[3] It was not until the 1870s, however, when settler Australians began to log them intensively.[4] Over time, the region developed an ambivalent reputation – both rugged wilderness and industrial frontier, a place apart from ‘civilisation’ and yet providing the raw materials for that civilisation.

We see both faces of ‘Karri Country’ in the Commercial Travellers’ Association collection. Photographers seemed to have visited the region several times on assignment for Australia Today. A 1923 photo depicts a timber bridge over the Blackwood River, karri soaring in the background, while another from the 1930s shows an orderly dirt road cutting straight through thick forest.

A number of photographs of the area date from the period 1936-1938: it is these that give us the strongest sense of the character of the place.

What was the purpose of depicting these seemingly primeval forests? Two answers readily present themselves: to show off a lesser known aspect of Australia’s scenery, appealing to recreational motorists, or to advertise one of its thriving primary industries, the same way a magazine might do a feature on WA’s mining sector today. But perhaps these images tapped into something deeper.

Let us home in on two photos, one from 1939, the other 1955. They are titled ‘Virgin Karri at Pemberton’ and ‘Virgin Karri forest, Pemberton, Western Australia’, respectively. This curious choice of words merits some further thought.[5] ‘Virgin’, of course, is here a synonym for ‘old-growth’, ‘unlogged’. However, none of the forest scenes in these photos, nor in those above, are unblemished by settler activity: in every photo of Karri Country we see some settler construction or artefact – a road, bridge or fence, a car or a train – and settlers themselves in at least two.

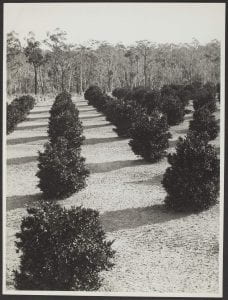

The ‘virgin’ forest was a synecdoche for Australia as a whole. These images promised the reader that Australia remained a place where a man could be an explorer or a pioneer, could be the first to make one’s mark on a place. In other words, it was a country still ripe for exploitation and development. This image of a mandarin orchard, with its orderly rows and manicured trees, nestled within ‘virgin bush’ (according to the item’s description) seems to encapsulate this vision of Australia.

These images assured the viewer that the destructive adventure of settler colonialism continued in the twentieth century: Australia was a country that still had its wild places, but the point of migrating here was to carve out a space for oneself within them. It was not enough to reverently appreciate a karri forest, as Noongar people did for tens of thousands of years – one had to build a road through it or cut it down for timber.[6] Virginity as a concept always implies its opposite – though we have no exact word for that state in English. Virginity exists, in other words, to be taken. The readers of Australia Today were invited to deflower Karri Country. That is to say, the beguiling implication of these photographs was that these forests were virgin for now – not forever.

[1] Karen McGhee, ‘Searching for Australia’s tallest trees: Karris’, Australian Geographic, July 2, 2014, https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/topics/science-environment/2014/07/australias-tallest-trees-are-karris/.

[2] John Dargavel, ‘Constructing Australia’s forests in the image of capital’, in Australian Environmental History: essays and cases, ed. Stephen Dovers (Melbourne: Oxford University Press Australia, 1994), 84.

[3] Eric Rolls, ‘More a new planet than a new continent’, in Australian Environmental History: essays and cases, ed. Stephen Dovers (Melbourne: Oxford University Press Australia, 1994), 25.

[4] Dargavel, ‘Constructing Australia’s forests’, 84-6.

[5] There are three other photos in the collection with the phrase ‘virgin bush’ or ‘virgin forest’ in the title: items 1979.0162.03109, 1979.0162.03169 and 1979.0162.03213.

[6] Noongar peoples did modify the tall forests of southwestern Australia, largely through careful fire regimes, but these modifications were subtle compared to settler developments and motivated by a very different cultural and economic rationale. Grant Wardell-Johnson et al., ‘The contest for the tall forests of south-western Australia and the discourses of advocates’, Pacific Conservation Biology 25, no. 1 (2019): 59-60.

Bibliography

Dargavel, John. ‘Constructing Australia’s forests in the image of capital’. In Australian Environmental History: essays and cases, edited by Stephen Dovers, 80-98. Melbourne: Oxford University Press Australia, 1994.

McGhee, Karen. ‘Searching for Australia’s tallest trees: Karris’. Australian Geographic, July 2, 2014. https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/topics/science-environment/2014/07/australias-tallest-trees-are-karris/.

Rolls, Eric. ‘More a new planet than a new continent’. In Australian Environmental History: essays and cases, edited by Stephen Dovers, 22-36. Melbourne: Oxford University Press Australia, 1994.

Wardell-Johnson, Grant, Angela Wardell-Johnson, Beth Schultz, Joe Dortch, Todd Robinson, Len Collard and Michael Calver. ‘The contest for the tall forests of south-western Australia and the discourses of advocates’. Pacific Conservation Biology 25, no. 1 (2019): 50-71.

Leave a Reply