Conducting historical research through digital archives, courtesy of the ‘Scan & Send’ service

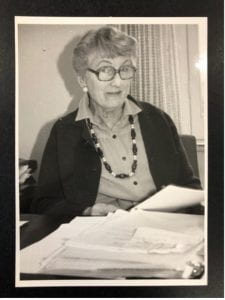

Noreen Minogue, early 1980s, Photographic series, (Control: AX36 PO4822), Australian Red Cross – National Office, University of Melbourne Archives

I recently completed my research thesis as part of the Bachelor of Arts (Honours) degree at the University of Melbourne. My thesis title, “The Inspiration Given To It By Women”: Noreen Minogue, Australian Red Cross, and the Development of International Humanitarian Law”, gives an indication of the nature of my historical inquiry. Considering the challenges that the COVID-19 pandemic brought to the academic community, particularly for those whose research depends on physical access to archives and university spaces, I was fortunate to be able to complete my thesis at all. Countless students and researchers owe a great debt of gratitude to the Archives team and the ‘Scan & Send’ service at the University of Melbourne, who made our research and contributions to the academic literature possible.

The ‘Scan & Send’ service is a wonderful example of innovation in education and archive collection management. From 2020, a skilled and dedicated team of archivists and technical experts digitally scanned and sent materials to the University community. Though this process certainly posed different resourcing requirements and labour disciplines for the team, the service revolutionised access to historical materials for students at the University. In this blog post, I hope to share a few reflections on my experiences completing a research thesis relying entirely on digital records.

Adjusting to digital research and the importance of building strong relationships:

For those used to poring over papers, photographs, documents, and materials from physical record collections, the transition to working with digital archives via ‘Scan & Send’ poses a challenge. I certainly missed the sensory experiences of examining dusty parchments, the thrill of physically discovering and holding important documents which shed new light on the past, and the camaraderie of working within an academic community in person. The Archival team were incredibly helpful (and patient) with me on my learning curve, as I wasn’t particularly adept at navigating archives in the first place. Email, phone calls, and infographic explainers were helpful to generate a deeper understanding about the system and processes to successfully conduct archival research through solely digital means.

Requesting materials:

Finding, requesting, and accessing digital records proved to be a more challenging process than when we were able to physically attend archives or reading rooms, where issues that arose could be trouble-shooted or worked through in person. Given the time-critical nature of the research and the significant workload on the Archives team, I found it particularly effective to triage materials by prioritising tranches of materials for the archivists, using the highlighter function on Excel. Having identified the priority boxes and materials, it was then a matter of requesting them via the request management system Aeon, where after the relevant records were scanned by the digital team and sent via CloudStor (a cloud-based file management system for researchers).

File Management:

The Archives team sent me large quantities of material. As such, it was crucially important to download and store these big and extensive files in an accessible and secure way. I used Google Drive to back up my files and sync them to my desktop, which allowed me to make digital notes, highlights, and comments on the archival materials as I progressed through them. File management is incredibly important. My advice: ensure you keep a master list of all documents you have on file, and correspondingly name the document files so that that they are easy to find and reference in future against the master list. I kept a ‘research log’ in Google Sheets, which included all critical information and high-level notes about the item numbers and materials I processed for easy reference.

Wellbeing, Reading and Writing:

Reading and taking notes on such large quantities of digitised archival records can be intimidating at first. It’s important to look after yourself while doing so, by ensuring as far as possible that you have access to an ergonomic chair, desktop monitors, and that you take regular breaks from the screen to preserve your eyesight and concentration. I found it helpful not to read the digital archival documents like a novel – i.e. end to end – unless I absolutely knew it was something that would be useful to my avenue of inquiry, which I discerned through headings and scanning paragraphs. Using the ‘control+f’ function to find key words worked on certain PDF formats, and saved a lot of reading time. Given the large quantities of digitised archival records, I found my research was ultimately a lot broader and deeper than it might have been from in-person research, and that I was able to process materials more quickly than usual. The most critical aspect of reading and research is taking well-referenced notes so that you can trace your materials back to the original source. Take down the file number, item title, and page number at a minimum to ensure you have everything to hand when it comes time to writing your thesis, referencing, and developing your bibliography.

Although moving to digital-first archival research is certainly a significant adjustment initially, I eventually came to enjoy the economy and flexibility of the process, which enabled me to tell a unique story using archival records that had not been previously utilised. There are certainly challenges to the digital-only approach, but these were outweighed by the goodwill and cooperation of the digitisation team, researchers, and supervisors.

Nick Fabbri

Nick Fabbri works and volunteers at Australian Red Cross in Emergency Services and is a part-time law student at the University of Sydney. He writes and podcasts at www.nickfabbri.com

Leave a Reply