Shuttered Histories: The Odyssey of John O’Brien’s Hanover St Residence

Ronak Alburz

John Lockyer O’Brien (1905–1965), a distinguished historian at the University of Melbourne, curated a remarkable collection of photographs, capturing the late 1950s and early 1960s. During a sabbatical in 1959, O’Brien’s historical curiosity led him to explore bluestone buildings, a subject that plausibly resonated deeply with his expertise. Most of these images were likely taken during this year, as he traversed inner suburban landscapes to document these structures.

These photographs offer a unique glimpse into the architectural and urban evolution of inner-city Melbourne during a time of transition. This era marked the shift from its 19th-century layout and working-class character to the eventual emergence of Housing Commission high-rise blocks. The subsequent return of the middle class to the inner city, accompanied by renovations and gentrification, further transformed the landscape captured in O’Brien’s lens.

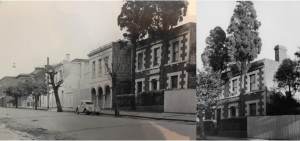

While exploring the collection, I found multiple photographs of John O’Brien’s own residence at 35 Hanover Street in Fitzroy (1965.0004.00279;1965.0004.00156; Fig. 3). These images capture various moments in the life of his house, including renovation shots, intriguing rooftop of the surrounding area views (1965.0004.00346; 1965.0004.00348; 1965.0004.00352; 1965.0004.00354; 1965.0004.00355; 1965.0004.00357; 1965.0004.00359; 1965.0004.00360 ) and many neighboring houses from the late 1950s. This stimulated my curiosity about his own house, given his role as a historian and the photographer and left me with the strong sense that there must be something truly special about House Number 35.

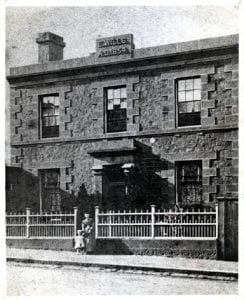

With a history that spans generations, this double-storey Georgian-style bluestone house – with its distinctive doric pilasters – has witnessed a series of ownerships. Originating in 1854, it was built by Edward Willis, a stonemason who supplied stone for the early parts of Parliament House and the first Princes Bridge (National Trust database, B0167), and the house’s parapet still bears his name. Joseph Gray, a skilled cooper, then acquired the property in 1868 and held onto it for an impressive 60 years. During Gray’s ownership, the house welcomed diverse tenants, including the Victorian Infant Asylum, later known as Berry Street, from 1877 to 1881. A fascinating photograph from around 1865 from Berry Street Archive, provides a window into the early life of the house, pre-dating images captured by John by 100 years (Fig. 4) 1 According to Laurie, in 1931, Sarah Nelis acquired the house, ultimately passing it down to her niece and nephew, Cliff and Edie Salmon, alongside the adjacent and ornate Montefiore Villa situated to the right of O’Brien’s bluestone house. While Cliff and Edie chose the villa as their residence, Number 35 saw life as a rental property again. The year 1956-57 marked a new chapter as John O’Brien and his soon-to be second wife Laurie (married in 1958) became the proud owners, continuing the rich legacy of this house.

However, a twist of fate unfolded as this era coincided with the onset of the slum abolition movement in Fitzroy, as illustrated in a news article published in the Herald newspaper (Fig.1), with the headline of “Slums are Up to You” noting the early work of the Brotherhood of St Lawrence, an Anglican charity.

At the same time, the local residents were organizing their own campaign with a “Slum Newsletter’ (Fig. 2).

Accordingly, in 1957, the National Trust established its “Survey and Identification” committee, and John O’Brien found himself a participant in this committee, as his historical expertise evidently sought after by The Trust. The committee established four distinct categories for houses, strategically determining which houses held national significance and cultural heritage worthy of preservation.

Nevertheless, upon acquiring the house in 1956-57, John and Laurie received reassurances from the Housing Commission that no further property acquisitions would occur on Hanover Street. This promise, however, would prove to be short-lived. In an unexpected turn in 1964, the Commission descended upon the north side of Hanover Street, and numbers 27 to 47 found themselves recipients of a “Notice to treat,” a decree that encompassed John O’Brien’s blue-stone residence too.

Fitzroy Council, in tandem with the Royal Historical Society and the National Trust, rallied in support of John, asserting the house’s value as a relic of colonial history deserving preservation. According to information from an oral history interview, as detailed on page 12 of the Fitzroy History Society’s records, Laurie attributed this accomplishment to Councillors Wood and Brodie. It is suggested that John may have initiated contact with them, leading to this achievement. This collective effort bore fruit in 1965, shortly before John’s passing, when a letter from the Commission declared an exemption for their house from compulsory acquisition.

Soon thereafter, a familiar scenario unfolded as Laurie received another letter from the Housing Commission, indicating the Commission’s interest in reopening negotiations. Evidently composing a letter infused with displeasure, Laurie effectively secures her position, compelling the housing commission to extend her tenure without restrictions. All these events occurred prior to the enactment of the Historical Buildings Preservation Act by the Hamer government. It is noteworthy that along the south side of Hanover Street, almost all houses underwent demolition and were substituted with maisonettes, except for a singular anomaly, 36-38 Hanover Street (1965.0004.00026; 1965.0004.00031; 1965.0004.00275; 1965.0004.00198). The circumstances surrounding the preservation of this particular house, facing number 35, also arouse curiosity, inviting inquiry into the reasons behind its exception.

In light of these circumstances, it is worth considering that, besides his personal campaigning to preserve their house, John’s membership in the “Survey and Identification” committee played a pivotal role in the subsequent reclassification and continued existence of this single house on the northern side of Hanover street.

This story has presented me with the opportunity to capture yet another photograph of House Number 35 for archival purposes, 158 years after the first photograph was taken (Fig. 5)! The enduring pine trees, standing tall and now towering over the beautifully renovated bluestone residence (– and far from the threat of ‘slums’.)

Ronak Alburz is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Melbourne, and her current research specifically investigates the transmission of knowledge, cult practices, and funerary traditions, with an emphasis on the influence originating from the Black Sea region and its impact on northern and central Italy in the Archaic Period.

References

- There is also another photograph of the house from 1988 in the Caroline Simpson Collection, record number: 38480. For ownership history see Fitzroy History Society. ↩

- According to Find & Connect, the original photograph is in the collection of Berry Street Archives. ↩

- Fitzroy History Society, page 13. There are two audio recordings of the interview on the Fitzroy History Society’s page. The first YouTube video, which is the full version of the interview, has a much lower sound quality. However, the above-mentioned quote regarding the reclassification of John O’Brien’s house can be found at minutes 5:40 through 6:10. The second YouTube video on the page has a higher sound quality, but it is a much shorter version of the interview. Interestingly, it starts with the third question on the transcript of the interview. The above quote was the answer to the second question, so it has been edited out of this shorter version. ↩

Leave a Reply