Early Views of Nuclear and the Anti-Nuclear Movement

David Trevorrow, Jessica Cunnington, & Clare Thorpe

The Records of the Congress for International Cooperation and Disarmament offer a fascinating insight into the history of the anti-nuclear movement in Australia. Though the hand printed leaflets and cartoons are largely of a bygone era, the messages contained within them remain salient to the recently reignited debate about nuclear energy. There also exist interesting historical parallels. Just as the Cold War shaped the 20th century debate around nuclear energy, so too does the AUKUS pact and Australia’s plan for nuclear-powered submarines today.

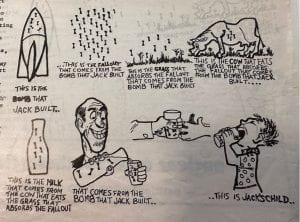

Figure 1 provides an example of Australian opposition to nuclear warfare. This cartoon comes from an information sheet protesting nuclear testing by France on Australian soil and in the Pacific. It also draws attention to the U.S. Omega base, a strategic navigation system eventually constructed near Sale, Victoria.

Characterising Nuclear Harms

The caricature of Jack and his child contains a range of emotive elements. The author gives Jack, the creator of a nuclear bomb and the unwitting distributor of fallout, an ominous smile to foreshadow the danger of his past and present actions. Jack’s unnerving smile also aims to instil in Australian readers a sense of wariness towards powerful supporters of nuclear energy and nuclear warfare. The cartoon also evinces a concern with the well-being of children and future generations, portraying them as scared, confused, and none-the wiser. The universal sanctity of children makes such depictions particularly powerful.

Not only are these cartoons social and environment statements, they also call into account those in positions of political power. Those in the crosshairs of the caricature include supporters of nuclear energy within Australia’s political establishment as well as the USA and key European powers. The broad aim of the caricature is to encourage Australian readers to band together in the face of the risks posed by nuclear energy.

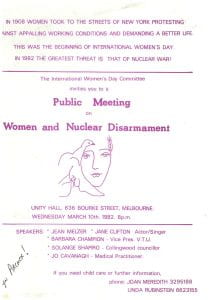

While very much involved in Australia’s anti-nuclear movement, feminist political materials took a different tack. As seen in figure three, the messaging does not revolve around traditional family values. Instead, it calls for the redistribution of funds to marginalised communities and invokes explicitly feminist understandings of equality. This continues in other pamphlets, where nukes are referred to as “boys with toys”. They also planned activities accessible to children, such as kite flying, to allow mothers to participate in political activities. Feminist anti-nuclear materials also included lyrics sheets for protest chants and songs. There were parodies of classic marching songs, for example, ‘Ban the Bloody A-Bomb’ sung to the tune of ‘John Brown’s Body’. The activities of the woman-led branches of the anti-nuclear movement thus aimed to widen participation in demonstrations and related political activities.

Interestingly, outside of the feminist wing and the Nuclear Free Pacific movement, anti-nuclear materials contain very little mention of aboriginal land rights or indigenous populations more broadly. This is somewhat peculiar given the interconnectedness indigenous self-determination and the issue of nuclear energy. Indeed, perhaps the biggest problem with the Maralinga nuclear tests were its effects on traditional owners of the land. The Ranger Report also arose during this period out of issues surrounding indigenous land rights. As such, one would have expected there to be a larger emphasis on aboriginal land rights in anti-nuclear materials.

Many of the arguments for and against nuclear energy in the 1970s parallel the contemporary debate. In a leaflet titled “Why stop uranium mining?”, the authors present the case for nuclear power as blinkered in that it insists that nuclear energy is “clean, safe and efficient”, while ignoring both the risk of major disaster and long-lasting nuclear radiation. The case against uranium mining focuses on the issues of radioactive waste, plutonium and nuclear weapons proliferation, nuclear reactor safety issues, and the risks of multinational companies controlling critical energy infrastructure.

Some aspects of the anti-nuclear argument – such as promoting fossil fuels as a better alternative to nuclear – are no longer relevant. However, the overarching appeal to instead invest in researching and deploying alternative energy options such as solar and hydrogen, and to reduce unnecessary energy usage, remain key to current conversations around the future of Australian energy. In short, the framing of nuclear energy in Australia remains heavily influenced by the nuclear debates of the 1970s. Further revitalising the protest movements of the 1970s may be necessary to thwart renewed calls for nuclear energy

Leave a Reply