Last week, the High Court published two unanimous judgments and announced a third, bringing its total of unanimous decisions so far this year to 15, out of 17 to date. At this early stage, the Court is tracking ahead of its past rates of unanimous assent in orders.* On my count of the last five years (since Gummow and Heydon JJ left the bench and Gageler and Keane JJ joined), the Court’s judges unanimously asesnted to the court’s orders in 75% (2013), 76% (2014), 81% (2015), 76% (2016) and 67% (2017) of three-or-more judge cases.This average unanimity rate of 76% over the past five years is – according to data compiled and generously supplied to me by regular blog commenter Matan Goldblatt – well ahead of earlier multi-year periods where unanimous orders made up 67% (2007-2012), 54% (2003-2007) and 61% (1998-2003) of High Court decisions. The backdrop (and possible explanation) of the current institutional unanimity rate is each judge’s personal rate of assenting to the Court’s order. From 2013, my count of those rates is: French CJ: 95.5%; Hayne J: 91.9%; Crennan J: 94.8%; Kiefel J/CJ: 97.7%; Bell J: 96.7%; Gageler J: 87.0%; Keane J: 97.1%; Nettle J: 91.1%; Gordon J: 90.0%; and Edelman J: 88.9%.

These figures show that the current court is characterised, not just by its lack of ‘Great Dissenters’ – Gageler J’s outlier of 87% is barely comparable to the likes of Kirby J (around 60%, dropping to 52% in 2006) and Heydon J (55% in his final year) – but perhaps especially by its run of ‘Great Assenters’ who dissent in fewer than 1 in 20 cases (including, in Kiefel J/CJ’s case, fewer than 1 in 40!) The rates of top three assenters of the current court (Kiefel J/CJ: 97.7%; Keane J: 97.1% and Bell J: 96.7%) all exceed those of the previous decade’s Great Assenter (Gummow J: 96.5%, based on Lynch et al’s annual statistics). Perhaps more so than dissenters, assenters are a product of who else is on the bench. I’ve calculated pairwise rates of agreements in orders (whether in assent or dissent) for the current seven judges as follows:

Unsurprisingly, the three highest rates of pairwise agreements (Kiefel & Keane JJ: 97%; Bell & Keane JJ: 94%; Kiefel & Bell JJ: 93.2%) are among the current court’s three Great Assenters. In the 108 cases to date where the trio of Kiefel, Bell and Keane JJ sat together, they agreed in orders 88.8% of the time.

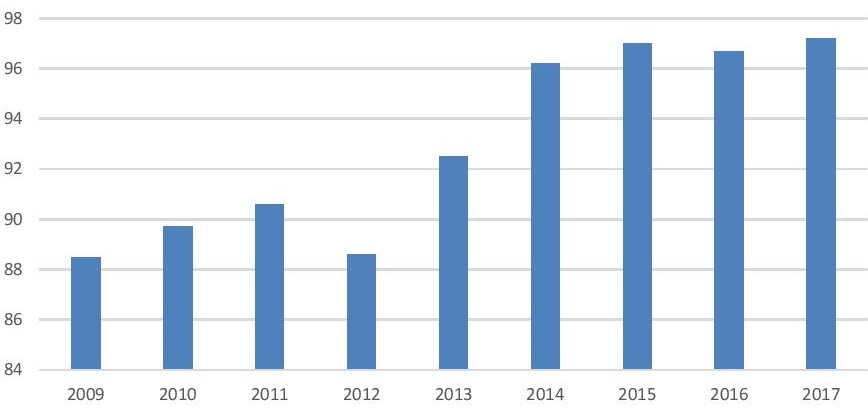

Why do pairs, trios or benches of judges routinely agree? Possible explanations include coincidence, the uncontroversial nature of cases they decide, the similar wisdom of the agreeing judges (great minds think alike), the shared legal approach of the agreeing judges (similar minds think alike) or what former High Court judge Dyson Heydon would term a ‘lack of independence‘, whether due to dominant personalities, excessive collegiality, a desire to present a united front, judicial politics or a division of labour. Only the Court’s judges (if anyone) know the explanation in each instance. Outside the Court, we can only look for patterns that hint one way or another. In that vein, as I compiled my own data, I happened to notice that the pairwise agreement in orders of Kiefel and Bell J was higher from 2014 onwards (97.20%, with just four disagreements in four years) than in 2013 (92.5%, with three disagreements in a single year). To explore further, I counted and charted the annual rates of pairwise agreements of these two judges since they first sat together in 2009:

Consistently with my hunch, this picture suggests a shift in Kiefel and Bell JJ’s pairwise agreement rate around 2013, switching from around three yearly disagreements on orders to just one (the same rate as Kiefel and Keane JJ throughout their time on the bench.) By contrast, perhaps the most famous of recent judicial pairs, Gummow and Hayne JJ, maintained their rate of agreement in orders of 95% (give or take half a percent) virtually unchanged from 1998 through to Gummow J’s retirement in 2012 (again using the data collected by Matan Goldblatt.) The cause of any possible shift agreements between Kiefel and Bell JJ in 2013 – the year Keane J joined the bench – is unclear.

*Note: This entire post is about judges agreeing on orders (that is, assenting to the same order, whether it’s the Court’s order or an alternative dissenting order.) It does not discuss the various other sorts of things judges can agree on. For example, in last week’s Burns decision, all seven judges assented in the orders dismissing the various appeals (and as to costs), but, as Martin Clark’s case note makes clear, they sharply disagreed 4-3 as to their legal grounds for making those orders. As well, only three judges gave a joint opinion explaining their reasons, although two others arguably agreed with each other’s reasons. By contrast, my sole concern above is with each judge’s assent to the same order – this is what matters to the litigants before the court (such as Garry Burns, Tess Corbett and Bernard Gaynor.) Other studies – e.g. Lynch et al’s annual discussion of judges joining eachothers’ reasons – explore different (and often less common), albeit still interesting, patterns of judicial agreements.

Methodology note: I derived my figures by looking through (a) the High Court summaries of cases back to 2013 to identify cases described as ‘unanimous’ (and to also identify three-plus judge cases); (b) the Austlli version of the cases to identify (i) the judges sitting in each three-plus judge case; (b) for non-unanimous cases, which judges assented to the orders and which did not. (This occasionally involved some tricky judgment calls on whether to treat a minor deviation from the order, e.g. as to costs, as a dissent.) Note that, on this methodology, tied decisions would classify the judges who agreed with the lower court’s (or, for original jurisdiction cases, the chief’s) orders as assenters and the rest as dissenters. I then put all of these results in an excel table, colour coded them and then manually counted each judge’s participation rate and the number of dissents, for each year, and then summed up and divided the relevant figures. My method is obviously susceptible to various errors, particular coding counting, arithmetic or typing errors, though I did my best to check the key figures and to recheck ones that looked odd (though that, in turn, could bias my results.)

Hmmm, Jeremy, “dissenter” has a clear meaning, but “assenter”? Sort of implies somebody else made the decision first and the spineless “assenter” went along with it (as the irascible Heydon insinuated). As you concede above, this is not necessarily true – and indeed is generally unlikely to be true, especially in a case like Burns where they make the same order for different reasons. We need a better word – though at the mom I can’t think of one.

Concurrer.

I originally had ‘agreerer’, which is no better and less grammatical. ‘Assent’ means assent in the court’s order, not assent with someone else. (Likewise, dissent.) So, I think it works.

If you google, you’ll see a small number of existing uses of ‘The Great Assenter’ or ‘The Great Assenters’, in some court contexts but also in religious contexts. E.g: https://books.google.com.au/books?id=hyvGCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT30&lpg=PT30&dq=The+Great+Assenters&source=bl&ots=hhM4MQlOPU&sig=xwqoXF8j9rqAI07w67Vs0K8sYEs&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjAx4yno9LaAhWh0FQKHVTIAn8Q6AEIgAEwCA#v=onepage&q=The%20Great%20Assenters&f=false

Apparently Willis Van Deventer (USSC New Deal era judge) was known as ‘The Great Assenter’ because he voted to strike down all forty-one laws struck down by the USSC during his tenure.

“Why do pairs, trios or benches of judges routinely agree?”

The answer to that question depends on the workload of the Court you are in.

In the case of the NSW Court of Appeal,only one judge has usually read the papers in full before the appeal hearing commences.The result is that unless the interest of the other judges is piqued by the argument,often the judgment is written by the judge who fully read the papers and the others concur.

A more interesting case is that where in the High Court special leave has been granted and in the course of argument on the hearing of the appeal the issue of whether special leave should have been granted arises.The most recent example of this was Govier v Uniting Church.The bench(Bell,Gageler,Nettle,Gordon & Edelman JJ) revoked special leave which had been granted by Bell,Keane & Edelman JJ.

Other than looking up the transcript,you won’t know this,as:

1.There is no judgment.

2.It is not included in the section of special leave dispositions

Further to my comment above,the High Court revoked special leave in Coshott v Spencer at the end of the hearing yesterday.Again you won’t know this from the Court records unless you read the transcript.