Yesterday’s decision by the High Court (sitting as the Court of Disputed Returns) in Re Gallagher means that there will have to be a recount of Territorians’ votes in the 2016 federal election to determine a new (hopefully eligible) Senator. Such recounts are relatively cheap things, as they are done electronically. The same is not true for the four by-elections that the decision’s reasoning indirectly prompted after four lower house MPs resigned. By-elections cost around $2M each. Together with the three other by-elections prompted to date and the $11.6M identified as post-budget ‘legal expenses – constitutional matters’ December’s mid-year statement, the cost to taxpayers of the dual citizenship issue so far as roughly $26M. These costs can’t, of course, be attributed to the High Court – the mere umpire in these matters.

But Tuesday’s annual budget – somewhat overshadowed by yesterday’s decision and its aftermath – reveals more about how much the High Court costs taxpayers. As is usual, the budget includes a financial statement by the High Court, as part of the Attorney-General’s Department portfolio, showing that the Court will receive $21.6M from consolidated revenue next year (up from $18.3M last year.)

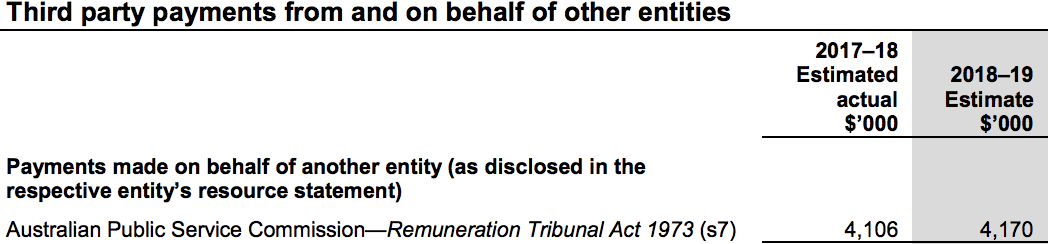

These figures do not include the seven justice’s own salaries or other allowances, which are ‘are paid by the Attorney-General’s Department from a special appropriation held by the Australian Public Service Commission.’ The budget papers list an unidentified payment from the Commission of $4.1M, rising to $4.2M next year, which seems consistent with the justices’ reported salaries of roughly $500K each: In total, the Court’s approximately fifty judgments per year cost taxpayers about $500K each to produce.

In total, the Court’s approximately fifty judgments per year cost taxpayers about $500K each to produce.

This year, there’s a further expense, announced as a new budget measure:

While the $4.5M in capital funding will seemingly be met by taxpayers, the recurring security expenses will be partly met by new annual revenue of $1.6M from increased fees imposed on all federal courts (apart from family proceedings), including $400K a year in High Court fees. As the High Court’s fees currently net around $2M a year, this implies that the current fees will increase by roughly 20%. The fees – for filing documents (including applications for leave to appeal and constitutional writs), hearings, obtaining documents and receiving services – are set out in the Court’s 2012 rules. They currently are indexed every two years, but that will change in future to annual indexing as a further budget measure.

What exactly is involved in the Court’s new security funding isn’t clear. The funding appears to be a response to a plea by Kiefel CJ reported in the High Court’s most recent annual report:

In May 2017, I wrote to the Prime Minister to seek the commitment, in principle, of the Government to assuming greater responsibility for the Court’s security through the use of the Australian Federal Police, on a model similar to that which has been put in place for the security of Parliament House. It is undoubtedly the duty of the Executive to ensure that the constitutional elements of Australia’s governments are protected. That has been recognised in the steps taken with respect to Parliament. In my letter to the Prime Minister, I said that it is difficult to see why, in principle, the approach taken to securing Parliament should not be extended to the High Court. In his response, the Prime Minister said that he had asked the relevant Minister to take responsibility for a comprehensive review of Court security requirements and to report with findings as well as specific recommendations on proposed security measures and how these may be implemented. The review was subsequently completed and the Court has commenced to implement such recommendations as it is capable of implementing. Implementation of sustainable security measures and improvements to the physical security of the High Court building will be subject to resolution of the funding principles to which I have already made reference.

In my view, a process where the Chief Justice must make such requests of the executive – especially just before the Court became embroiled in a series of cases tied to the government’s political future – is very unsatisfactory. It would be much better if, like the judges’ own salaries, such needs were assessed and dealt with at arms’ length from both branches of government.

Interesting article. Adequate funding and governance of courts administration has been a long-standing problem. Politically, few give a stuff about the effective administration of justice: they seemingly care only about the front and back-ends—policing and gaols. SA experimented with a model of courts admin run by a council of their own judges which I understand was pretty effective, although didn’t solve the access to funding problem.

The parliament, as the first arm of govt, doesn’t have this problem of course because all members of the political executive are also members. They’re hardly going to impose restrictions upon themselves.

Wouldn’t it be correct to say, rather than ‘2012 Rules’, the Regulations determined by, and prepared on instructions from, the Attorney-General’s Department? The Court does not set its own fees.