By Dr Alysia Blackham

Quest South Perth Holdings Case Page

In Australia, workers may be engaged as employees or as self-employed independent contractors. Employees are entitled to a range of employment rights, but independent contractors are not — after all, they are not employees. ‘Sham self-employment’ is where individuals are supposedly engaged as independent contractors, but they are actually employees. Cases where employers have misrepresented employees as being independent contractors are increasingly prevalent, affecting well-known companies like Myer (here and here), Australia Post (here) and the MCG (here and here). This may significantly affect workers’ terms and conditions of work — for example, cleaners employed as ‘independent contractors’ at Myer (via cleaning contractor Spotless) alleged that they were paid less than casual employees, did not receive penalty rates and had to pay their own tax, superannuation and insurance (see here and here).

Sham self-employment has again come on to the political agenda, thanks to the High Court case of Fair Work Ombudsman v Quest South Perth Holdings Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 45, which was handed down on 2 December 2015. Under s 357(1) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), an employer ‘that employs, or proposes to employ, an individual must not represent to the individual that the contract of employment under which the individual is, or would be, employed by the employer is a contract for services under which the individual performs, or would perform, work as an independent contractor.’ Section 357(1) does not apply where the employer proves that, when the representation was made, the employer:

(a) did not know; and

(b) was not reckless as to whether;

the contract was a contract of employment rather than a contract for services (s 357(2)).

A three-way relationship

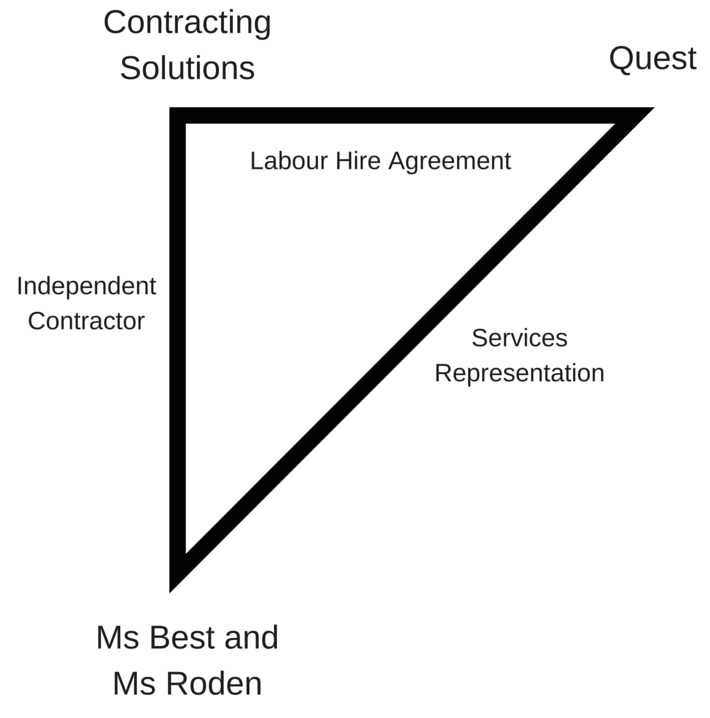

In FWO v Quest, the issue for the High Court was whether s 357 applied to labour hire arrangements. Quest had previously employed Ms Best and Ms Roden as housekeepers. Quest then entered into a triangular contracting arrangement, whereby Ms Best and Ms Roden would be engaged as independent contractors by Contracting Solutions; and Contracting Solutions would provide the services of Ms Best and Ms Roden to Quest under a labour hire agreement. Quest then represented to Ms Best and Ms Roden that they were independent contractors of Contracting Solutions. In fact, Ms Best and Ms Roden continued working for Quest in the same manner as before.

Figure 1: The Triangular Contractual Relationship in Quest

The question for the High Court was whether s 357 covered Quest’s representation — that is, a representation that employees were independent contractors of a third party, when they were still employees of the employer making the representation. The Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia held that it did not; the High Court overruled this decision and held that it did. The High Court’s decision in this case is refreshingly pragmatic: according to the joint decision, there was nothing in s 357 that required it to be confined to two party situations; indeed, s 357 ‘is silent as to the counterparty to the represented contract for services.’: at [15]. The counterparty is therefore ‘immaterial’: at [15]. Confining the section would prevent s 357 from achieving its purpose — that is, protecting individuals from being misled about their employment status, and therefore their entitlement to employment rights: at [16]. The construction would also be ‘capricious’, as employers could avoid penalty by making representations about a third party — even if that third party was ‘entirely fictitious’: at [17]. This purposive interpretation was supported (or, at least, not prevented) by the legislative history of the section: at [18]–[22].

This decision accords with common sense and the general purpose of s 357. If we are to avoid sham contracting and misrepresentations of self-employment, employers cannot and should not avoid liability by interposing a third party into their contracting arrangements. If the High Court had not overturned the decision of the Full Court, this would have severely affected the efficacy and purpose of s 357. Thus, the decision in FWO v Quest is to be welcomed as a logical and practical interpretation of the FWA.

A problem: the murky meaning of ‘employment’

At the same time, this case flags ongoing challenges in relation to self-employment. Section 357 (and employment law generally) is still battling significant uncertainty regarding who is an ‘employee’, and what constitutes ‘employment’. The common law definition of employment is complex and fact specific, meaning it can be difficult to assess who is entitled to employment rights without a judicial decision. In this uncertain landscape, employers may well be able to argue that they did not know, and were not reckless as to whether, the contract was a contract of employment rather than a contract for services under s 357(2), particularly where they have received contrary expert advice on the issue (see Helen Anderson, ‘Fraudulent Transactions Affecting Employees: Some New Perspectives on the Liability of Advisers’ (2015) 39 Melbourne University Law Review 1). If employers and advisers cannot determine whether someone is an employee, what hope and success can workers possibly have in assessing their own rights? This reinforces both the importance of a provision like s 357, which aims to prevent employees from being misled, and the fundamental limitations of relying on employees to enforce their own rights in this context. The role of the Fair Work Ombudsman in enforcement, as in this case, is absolutely fundamental. Fortunately the FWO has continued to cite self-employment and sham contracting as one of its areas of priority.

Where have the self-employed gone?

More generally, however, it is interesting to consider how widespread these issues are likely to be in Australia. With economic uncertainty and a difficult financial climate, it would not be surprising (though certainly disappointing) if employers were increasingly looking to sham arrangements to reduce their labour costs. Thus, we would expect to see an increase in self-employment since the Crisis. Interestingly, however, we actually see a decrease in self-employment in recent years — both in absolute numbers and as a proportion of the overall workforce. This stands in stark contrast to other countries, such as the UK, where self-employment has increased markedly.

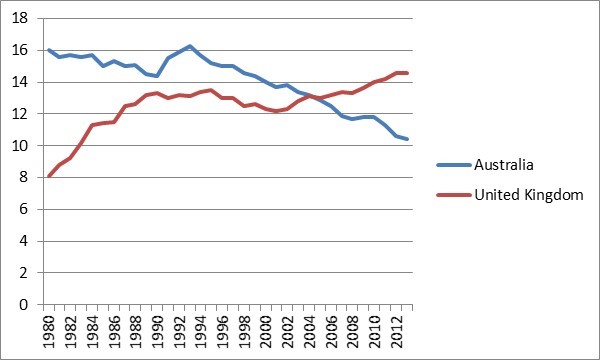

Figure 2: Self-employment as a per cent of all employment (Source: WorldBank, http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.EMP.SELF.ZS)

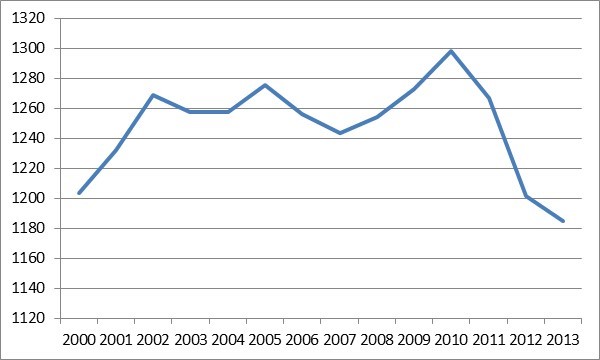

Figure 3: Self-employment (‘000s), Australia, 2000-2013 (Source: OECD ALFS)

The noticeable drop off in self-employment since 2010 in absolute figures is staggering: though, as can be seen in Figure 2, this is part of a more stable trend away from self-employment. This could be partly attributable to s 357 and similar provisions (originally introduced by the Workplace Relations Legislation Amendment (Independent Contractors) Act 2006 (Cth), and simplified in the FWA). Labour hire arrangements have also remained relatively stable as a proportion of all employment in recent years, though shifting from 8% of all employment in 2001; to 5% (or 576,700 persons) in November 2008; to 5% (or 605,400 persons) in November 2011; to 5% (or 599,800 persons) in August 2014.

Thus, these issues affect a small but sizeable minority of the Australian workforce, and should continue to be the subject of debate and study. At the same time, we need to ask why self-employment is declining in Australia — has the FWA effected this change? Or is this the result of broader economic conditions in Australia? The answers to these questions will prove particularly telling, especially for countries trying to counter a massive growth in self-employment — like the UK.

AGLC3 Citation: Alysia Blackham, ‘Sham Self-Employment in the High Court: Fair Work Ombudsman v Quest South Perth Holdings Pty Ltd‘ on Opinions on High (7 March 2016) <https://blogs.unimelb.edu.au/opinionsonhigh/2016/03/07/blackham-quest>.

Dr Alysia Blackham is a Lecturer at Melbourne Law School.

Some very interesting questions and statistics.

Anecdotally, the crackdown on sham contracting was so pervasively rumoured in commercial practice (however widespread the actual crackdown was) and so often led to clients choosing not to try and structure their workforce as independent contractors without being sure they legitimately were, that I can believe the law- and the threat of enforcement of it- changed behaviours. It’d be worth researching to know for sure, though, as most research I’ve seen into laws changing behaviours have focussed on either criminal law or tax/excise.

Of course, the breakdown of these figures by industry would also be interesting to see so that we could filter out any effect that comes just from industries with high self-employment percentages suffering a relative decline.