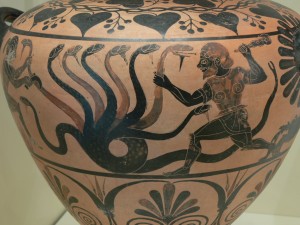

In September 2013, it appeared that the Hydra had finally been slain: the long-running, complex and expensive Bell Group litigation had settled just before the hearing of an appeal to the High Court. However, just like the Hydra of myth, it appears that where one head of litigation is cut off, at least one other will grow. The High Court has just ruled in Bell Group N.V. (in liquidation) v Western Australia [2016] HCA 21 that the Bell Group Companies (Finalisation of Matters and Distribution of Proceeds) Act 2015 (WA) (‘Bell Act’), under which the $1.7B settlement sum was sought to be distributed, is constitutionally invalid. The legislation was rushed through the Western Australian parliament last year, but last-minute amendments made in April this year were insufficient to save it. It seems likely that the Bell litigation will continue, as litigation had previously been both threatened and commenced after settlement and prior to the enactment of the Bell Act.

As I have noted previously, the Bell litigation was funded by the WA State Government-owned Insurance Commission of Western Australia (ICWA). Western Australian motorists paid an annual levy of $50 on third party insurance from 1993 to 1996, known as the WA Inc levy. The Western Australian government created a statutory authority to disburse funds pursuant to the Bell Act. Among the major creditors were ICWA and the Australian Tax Office. The presence of the latter as a creditor was pivotal in the resolution of the recent High Court case. Section 4 of the Bell Act seemed to contemplate that the party which funded and took the risk of litigation (ICWA) should get a greater share of the settlement funds because without its actions, there would be no funds available for other creditors at all. However, as Stephen Bartholomeusz reports in The Australian, this distribution was not in accordance with the way in which such funds are typically distributed, as ICWA was an unsecured creditor who would typically rank below the other creditors in a normal administration:

Its [the Bell Act] administrator had proposed giving ICWA $930m of the $1.8bn at stake, despite the fact that ICWA was an unsecured subordinated creditor of the Bell Group, ranking behind the ATO and holders of Bell’s unsecured but unsubordinated bonds. The biggest of those higher-ranking creditors is a Dutch billionaire, Louis Reijtenbagh, who bought bonds at a discount in the 1990s, along with another group led by litigation financier Hugh McLernon.

As it was the major funder of the litigation against Bell’s banks that resulted in the pot of gold for the creditors, ICWA might have a moral case for a meaningful share of the $1.8bn. Its legal entitlement, however, could be as little as $3m of unpaid rent from Bell’s occupancy of an ICWA building in the 1980s.

Now that it [sic] attempt to have its own administrator decide how the $1.8bn would be distributed, with ICWA already designated as the major beneficiary, the government and ICWA are at the wrong end of the creditors’ queue. Conventionally, after the ATO and other higher-ranking creditors have been paid their entitlements, ICWA might get what’s left.

As Martin Clark has described in his excellent short note on the decision here, the entire Bell Act was struck down as invalid because it was inconsistent with Federal law (see s 109 of the Constitution). Specifically, the Bell Act was inconsistent with provisions of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth) and the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) (collectively, the Tax Acts). The essence of the decision can be gleaned from [9] of the plurality’s judgment:

The Bell Act purports to create a scheme under which Commonwealth tax debts are stripped of the characteristics ascribed to them by the Tax Acts as to their existence, their quantification, their enforceability and their recovery. The rights and obligations which arose and had accrued to the Commonwealth as a creditor of the WA Bell Companies in liquidation, and to the Commissioner, under a law of the Commonwealth prior to the commencement of the Bell Act are altered, impaired or detracted from by the Bell Act.

Gageler J also invalidated the Bell Act on a ‘narrower basis’, namely, that ss 22 and 29 of the Bell Act were essential to the scheme. These provisions respectively outlined the transfer of property to the Authority for distribution and the powers in regard to that property, and granted the Authority the power to administer the company. These provisions would alter, impair or detract from the operation of s 215 (which deals the pre-tax liabilities of a company in liquidation) and s 254 (which deals with the post-tax liability of a company in liquidation) of the 1936 Act, and consequently were inconsistent.

In any event, as a result, the Bell litigation lives again for another day.

An interesting aspect of this decision is the way the joint majority applied the concept of legislative intention as part of their reasoning for concluding that the offending provisions cannot be severed from the Act.

At [70], they state: ‘The offending provisions are so fundamental to the scheme of the Bell Act and thus so bound up with the remaining provisions that severance of the offending provisions would leave standing a residue of “provisions which the State Parliament never intended to enact”’ (citations omitted).

That reasoning makes sense only if it is accepted that the legislative intention is capable of pre-existing its construction by the courts, at least in cases where the intention is clearly manifested by unmistakable and unambiguous statutory language.

This notion that the legislative intention may pre-exist its construction by the courts could be viewed as being inconsistent with the following assertions made by six members of the High Court in Lacey v Attorney-General (Qld). They asserted that the legislative intention is not an objective collective mental state, that such a state is a fiction and that the legislative intention is ascertained by applying the rules of construction.

However, it is important to note that the High Court has not determined that legislative intentions per se are fictional. Rather, the Court has determined that the ‘objective collective mental state’ is a fiction.

When legislative intentions are conceptualised as intentions taken to have been acted on by Parliament through legislation giving effect to those intentions, it can be seen that some of the legislative intentions ascertained by the courts are real intentions that pre-exist their construction by the courts. Like the courts, legislatures have decision-making rules that enable them to act on the prevailing intentions formed or adopted by their individual members. As pointed out by Charles Fried, ‘words and text are chosen to embody intentions’. Of course, it remains to be seen whether the High Court will adopt this conception of legislative intentions.

Thanks Jim. You are right – the approach taken to intention is an interesting one. It seems to me that sometimes a collective intention can pre-exist determination by the court, and that the legislation in this instance may be such a case. The High Court’s approach to intention more generally is also interesting (I’m thinking here of Byrnes v Kendal, the trust case where the trustee could objectively create a trust when he subjectively did not intend it – because the formal documents evinced an intention).

Thanks Katy. The suggested conception of intentions can be clarified by using a simple analogy. Suppose the following: (1) You are a member of a five-person selection panel. (2) You form an intention to nominate a particular candidate for appointment. (3) Two of the other members also form that intention. (4) The panel acts of the prevailing intention by nominating the particular candidate.

This analogy demonstrates that, provided the necessary decision-making rules are in place, it is possible for a group such as a legislature to act on the actual intentions of individuals. This is so even if the view is taken that collective intentions don’t exist as a group doesn’t have a mind.

Acceptance of this conception of legislative intentions would not affect the way Australian courts ascertain legislative intentions under the existing rules of construction. What counts for constitutional purposes is the intention manifested by the statutory text and context, not the subjective intention of any individual. Legislative power is a power to enact legislation; it is not a power to govern by unlegislated intentions.