Uninvited guests in your groceries

Words, illustraions and photos: Marianne CoquilleauMarianne Coquilleau

With spring coming our way, gardens come to life and with it their many inhabitants. It’s no surprise then to find small caterpillars, aphids and other insects while washing your vegetables and fruits, especially if you source your vegetables locally or pesticide-free sources. You might then also notice some little lines on your leafy greens, like pale squiggles on the surface. Fear not! You’re simply sharing a meal with a little fly larva, a leafminer maggot.

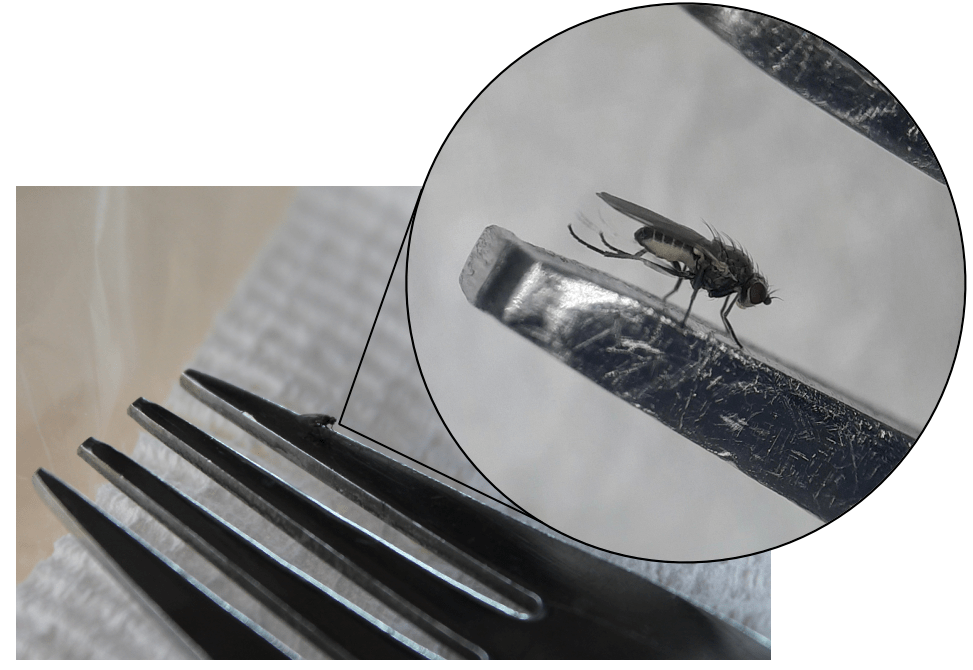

My Masters project at PEARG had to do with the different species of agromyzid leafminer flies found around Melbourne and the tiny parasitoid wasps that attack them. The adult flies are incredibly small, 2 mm at most, and lay their eggs under the epidermis of the leaves. The small larva then hatches, and feeds within the leaf, burrowing a little tunnel as it grows. It would be a bit like sleeping, living and eating in a duvet stuffed with edible down! Once the larva has reached maturity, it will either pupate straight into the mine, forming a hardened cocoon, or chew a little opening and pupate in the soil. Once the fly emerges, all it leaves behind is a white trail on the plant.

An adult chrysanthemum leafminer, reared from sow thistle and posing on a fork for size reference.

Some of the most common leafminer flies found around Melbourne and Victoria actually arrived by tagging along with European settlers, by hiding, you’ve guessed it, in their food but also in soil as pupae, or forage brought in for livestock. These flies do not have a pest status but can be found in some crop plants and thus appear in your groceries.

Stay on the lookout for mines in your lettuce leaves, made by the chrysanthemum leafminer (Phytomyza syngenesiae), and some a little less visible in spinach, chard, or beetroot leaves, by the beet leafminer (Liriomyza chenopodii).

Take a close look at your radish tops and you might see a mine left by the cabbage leafminer (L. brassicae), which as its name indicates will happily eat any Brassica plants or ‘cole crops’.

You’re likely to notice them in slightly older leaves, where the mining larvae has had time to feed and produce a visible tunnel.

Some mines I found earlier this month from garden-grown edible chrysanthemum leaves (by P. syngenesiae)

My advice: no need to fuss over the fainter marks, and you can simply tear off the bits with visible mines or of course discard the most damaged leaves.

Interestingly, a lot of their weedy host plants – plants you wouldn’t find at a market – can be foraged and are cultivated or cooked in some countries. In a way you could say we’re the ones eating the leafminer flies ‘groceries’!

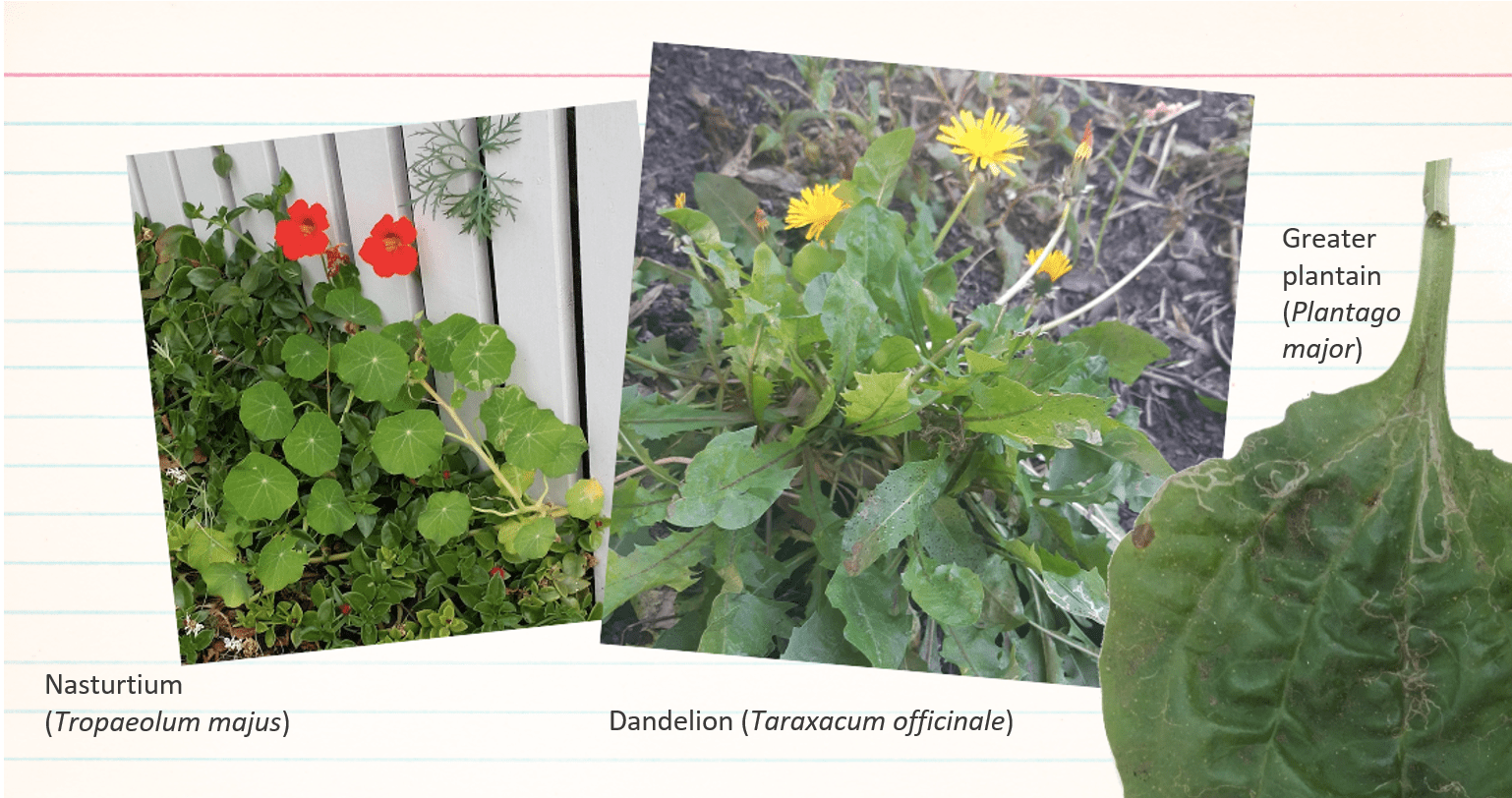

Sow thistle (Sonchus oleraceus) is a very common weedy plant, with yellow flowers and pointy leaves that is often mined by the chrysanthemum leafminer. The flower buds can apparently be pickled into a caper-like condiment.

Young dandelions leaves (Taraxacum officinale), another favorite of the chrysanthemum leafminer, can also be used in salads.

The same is true for chickweed (Stellaria media), a small ground-cover plant with tender bright green leaves that is mined by the beet leafminer.

From the cabbage leafminer’s basket you’ll find that young leaves from wild brassicaceous weeds, like the twiggy turnip (Brassica fruticulosa), can be blanched much like spinach, and sea rocket (Cakile maritima) is a crunchy addition to salads.

One of my favorite is nasturtium (Tropaeolum majus), also mined by cabbage leafminer larvae, that has edible leaves and flowers, with a lovely peppery taste.

A few examples of the plants favored by the leafminers. Can you spot the mines?

A very common weedy plant around Victoria is plantain, either ribwort plantain (Plantago lanceolata) or greater plantain (Plantago major). Historically, their presence is an indicator of European settlement, and their leaves and seeds can be eaten in different ways. They were introduced from Europe and with them came the plantain leafminer (P. plantaginis). You can find them mining under the leaves, at the base of the plant, protected from predators.

Purslane (Portulaca oleracea) is another plant to look out for, its succulent-like leaves can be steamed, sautéed or eaten raw in salad. But first, check for the very large mines made this time not by a fly larva but instead by the larva of a sawfly, which despite its name is more closely related to wasps.

Now, I would not advise foraging for edible weeds simply due to the risks of misidentification and because you never know if they were sprayed or what animal, pet or possum, came by and left their mark. If you are interested however, there are guided tours (here and here) for local Melbourne plants as well as websites and books to check out for information.

In the meantime, keep an eye out for white squiggly lines left by these little flies, you’ll be surprised how many you can find once you start looking for them, whether they be in your groceries or in plants growing by the sidewalk.

Grâce à toi, nous ne regarderons plus nos légumes de la même façon…