Faster and cheaper without compromising quality

Words: Nick Bell

When our scientific endeavours leave the lab and move into real-world deployment, a number of challenges crop up. Aside from obvious issues around myriad variables that cannot be controlled as they can in the lab, large scale logistical and financial considerations need to be made when rolling out new operations. This scaling issue becomes acutely important where a project is being delivered in less developed nations. Local availability of lab facilities and expertise can cause issues around quality control and monitoring. In order to maximise the scale of implementation and overall efficiency for a successful outcome, operational costs must be minimised.

We identified an area for improvement around crucial routine monitoring in current Wolbachia release programmes. Until now, accurate post-release monitoring has been largely contingent on having a highly trained local team of scientists with access to state-of-the-art facilities. With this challenge identified, we began a search for practical solutions. We needed a cheap, fast, simple yet highly accurate means to monitor the Wolbachia infection status of mosquitoes. Our literature search landed on a methodology called “LAMP” or Loop-mediated isotheral amplification as a promising means to this end. Numerous LAMP assays have been developed over the past 20 years for a variety of screening diagnostics where accurate detection (true/false) is more important than exact quantitative measurement.

And critically for us, we had a new toy in the lab – the Genie MKIII, a relatively cheap and fully portable device that performs LAMP assays with high fidelity and minimal training requirements. This machine runs off batteries, can be recharged in a car, and uses a smartphone as its computer.

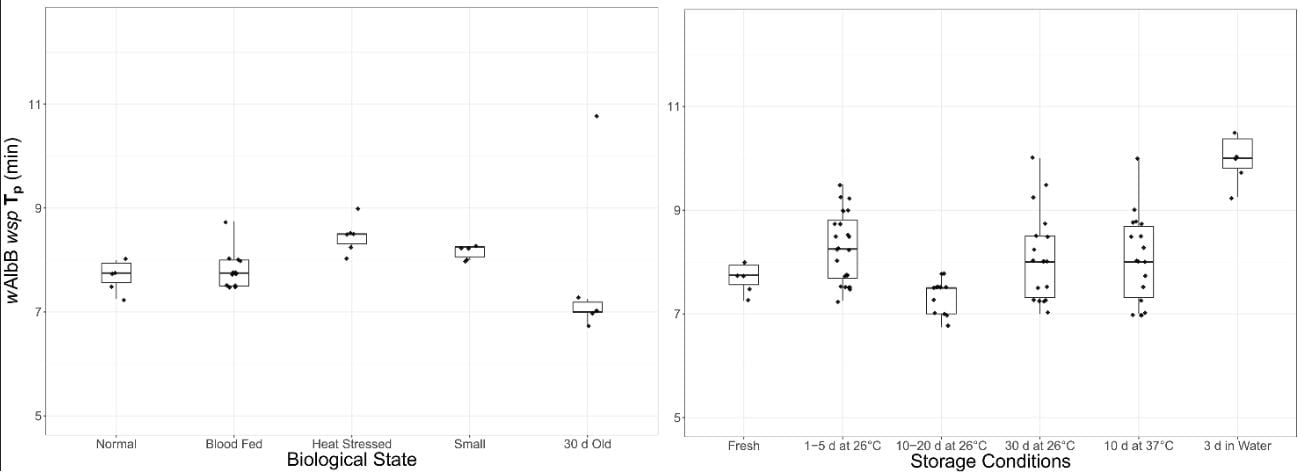

In our new paper freshly published in PLOS ONE we describe our simple, rapid and robust methodology. Particularly exciting was how sensitive and reliable the assay proved to be. We stored dead mosquitoes in real-world sub-optimal conditions that frequently stymie traditional assays. Dead mosquitoes were kept in water for three days, some were dried out at high temperatures (i.e. 37°C) for a full week, and we still had reliable detection. Even mosquitoes left to dry out at 26°C for an entire month presented no issues to this assay.

Our next plans involve the development of assays for other important monitoring issues such as pesticide resistance in mosquitoes. The rapid identification of other insect species of biosecurity significance that are difficult to determine by visual inspection is also an area we want to explore.

.