The grasshopper that was lost, then found, is now endangered

This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.

By Professor Ary Hoffmann, Vanessa White and Professor Michael Kearney

The Key’s Matchstick Grasshopper, or the Keyacris scurra, was once widespread and abundant in New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory and north-central Victoria, but over the past century its numbers have seriously declined.

So much so that in NSW, it has now been declared endangered.

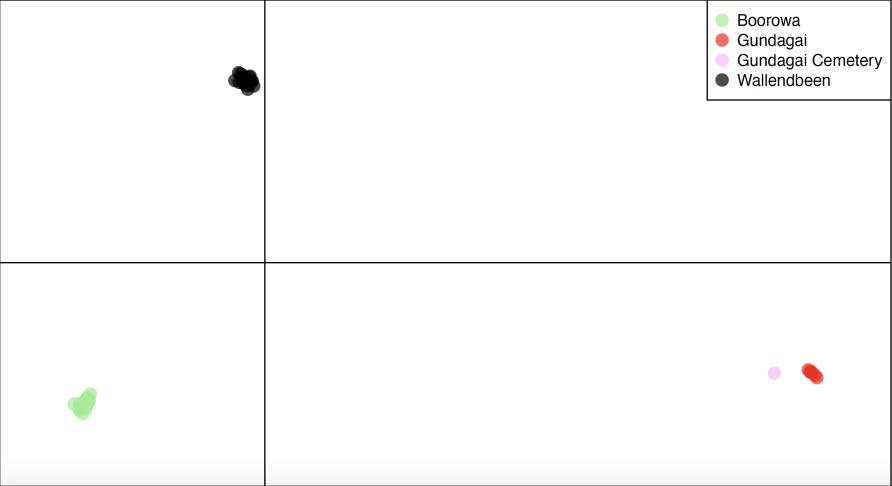

The distribution of Key’s Matchstick Grasshopper has contracted to such an extent that its habitat is now severely fragmented and shrinking.

The species was once found in an area covering 15,906 km², – but it now occupies only 68 km² which represents a loss of 96 per cent of its range.

A SHRINKING ENVIRONMENT

As agriculture expanded, vast tracts of land where the grasshopper once occurred were cleared. The native daisies and grasses that the grasshopper relied on were replaced by ‘improved‘ pasture that was considered more suitable for livestock grazing.

Rediscovering a ‘lost’ species

In addition, remnant areas of vegetation around rural and regional cemeteries that were once a stronghold for any remaining grasshopper populations have been lost through mowing and further clearing.

The grasshopper’s own biological attributes have also not helped its chances of survival.

It is flightless so it’s likely to move only meters, rather than kilometres, across its lifespan.

This means the grasshopper is restricted to local patches of suitable native vegetation that have become increasingly fragmented by land clearing.

Without the ability to move very far, the grasshopper is effectively trapped and, as a result, can only form small disconnected populations that are expected to diverge genetically.

Our recent genetic data obtained from sampled populations within the grasshoppers’ remaining populations confirms this pattern.

Each remaining population of Key’s Matchstick Grasshopper appears to be genetically unique, and distinct from nearby populations that might only be a few kilometres away.

This highlights the absence of gene flow between these population fragments which can result in problems such as inbreeding. But it also makes the grasshopper populations susceptible to local extinction if fire or other catastrophes affect a fragment or small pocket of their population.

Grasshoppers: The new poster bug for insect conservation

Fire is a particularly important issue for this species. Unlike most grasshoppers, the Key’s Matchstick Grasshopper spends the winter as an immature grasshopper (a nymph) above ground, rather than as an egg underground. So, they are vulnerable to control burns carried out in the cooler months.

This issue could be resolved by ensuring that controlled burns are patchy in the grasshoppers’ favoured habitat.

But policies like this need to be developed quickly because many burns are planned for this spring and additional habitats – and potentially grasshopper populations – may be destroyed in the looming fire season.

LOSING AUSTRALIAN BIODIVERSITY

Although small grasshoppers may not capture the public imagination the way colourful parrots or cute furry mammals do, they nevertheless represent an important and unique loss of Australian biodiversity.

Key’s Matchstick Grasshopper is an example of a ‘morabine’ grasshopper, an Australian family of flightless grasshoppers found nowhere else in the world that were first studied by renowned Australian biologists like CSIRO entomologist Dr Ken Key and geneticist Professor Michael White.

Coming to the genetic rescue of our endangered marsupials

They are harmless animals, feeding only on native plants, but they are an important component of the food chain for other native animals including birds and lizards.

The species can be abundant locally, particularly in winter and early spring. These are times when other types of insect prey are scarce so they contribute important supplementary protein into the food chain in colder months.

Because these grasshoppers can be bred in captivity and can be maintained in enclosures in the field, there are opportunities to restore populations in areas where suitable vegetation can be re-established.

Revegetation provides an opportunity not just to plant trees, shrubs and grasses but also to restore the landscape more generally, including the invertebrates that once lived in these places.

Consequently, there will be a positive flow on effect to other aspects of the ecosystem.

An understanding of the unique genetic diversity of existing and future populations will also play a key role in the survival of this species.

STRATEGIES FOR SURVIVAL

The Key’s Matchstick Grasshopper is just one example of a small native invertebrate threatened through processes like livestock grazing.

The invasive fungus threatening Earth’s biodiversity

There are other grasshoppers and small invertebrates in the same predicament that could likely be helped through management actions, but a consistent strategy remains lacking.

The history of the Key’s Matchstick Grasshopper highlights the extent to which an animal that was once highly abundant across hundreds of kilometres of Australia is now only found in a few fragmented locations.

Its fate also reflects the massive environmental changes that have occurred as a result of our actions during the past 200 to 300 years – changes that continue today.

Nevertheless, somehow, this small grasshopper has managed to survive.

There are also some marsupials that were once abundant but are now endangered. Eastern barred bandicoots were common across the volcanic plain of Victoria but are now restricted to a few highly protected reserves.

While animals like the bandicoots may receive a lot of attention, given their uniqueness and ecological importance, invertebrates like the Key Matchstick Grasshoppers deserve their moment in the spotlight too.

This work is being funded by an Australian Research Council grant to develop conservation strategies for insects with support of Zoos Victoria, who have made Key’s Matchstick Grasshopper one of their Fighting Extinction priority species, and from VicRoads who are helping to manage roadside habitat in Victoria.

Banner: Michael Kearney/University of Melbourne