Q&A: Victoria’s monster mosquito explosion

By Véronique Paris, Nick Bell and Professor Ary Hoffmann

This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.

It’s evening and you’re just starting to relax after a hectic day. Just as you do, you hear the unmistakable high whine of a circling mosquito. It’s something most of us are used to in Australia, but does it feel like it’s happening more often this spring? Or that there are more of those blood suckers around on the hunt for a meal?

We asked three University of Melbourne experts – PhD candidate Véronique Paris, Nick Bell and Professor Ary Hoffmann from the Faculty of Science’s Pest and Environmental Adaptation Research Group to explain exactly what’s going on.

Q) Are there actually more mozzies this spring or are we just noticing them more?

Yes, there do appear to be more mosquitoes around this year, you are not imagining things. It’s something we’ve noticed ourselves.

As part of our research, we carry out surveillance around our laboratory space and offices to check for mosquitoes that might contaminate our research colonies and have recorded far more this year.

Because we run a lab where we breed mosquitoes for research, it’s important we make sure these aren’t escapees. All the mosquitoes around our offices have been identified as Culex species, which we aren’t currently keeping in our research insectary, which tells us these aren’t escapees but invaders.

Obviously because our friends and family know that we research mosquitoes, we get a lot of messages and calls about the surge they’re noticing in mosquitoes. And of course, everyone wants advice on how to control them.

As our team does a lot of work out on the field around regional and rural Victoria, it’s something we’ve noticed in our field sites as well.

But it’s not just Victoria where we’re seeing more mozzies – New South Wales is seeing explosive mosquito population increases, and local experts are anticipating it is far from over.

Given we know these mozzies haven’t come from our labs, we are doing some genetic screening to determine which species these mosquitoes belong to. Interestingly, we suspect these ones aren’t a human-biting species as the team has noted that they do not try to feed on us when we’re in the building.

Q) Why are there more mosquitoes this year?

The heavy rains in southeast Australia are likely to be a big factor.

All mosquitoes require water to complete their lifecycle, with some species specialised to breed in very small containers like old tyres, discarded plastic containers and tree holes. Other species prefer larger water bodies like water tanks or ponds.

Many pest mosquitoes breed well in standing water rather than flowing water, and the recent rain and flooding have produced a lot more standing water.

This often includes new ‘cryptic breeding sites’ – places that can be harder to access like under houses, in garages and in the bits and pieces of junk many of us let build up around the backyard – cleaning it up will mean you’re doing your part in keeping the mozzie population down.

Most mosquito species develop quickly in warmer conditions, so the combination of heavy rains and increasing temperatures as we approach summer provides mozzies with the ideal conditions for their populations to boom.

Q) Mosquitoes seem bigger, Should we worry about that?

Mosquitoes vary in size from very small to quite large.

There are more than 300 species found in Australia, and around 10 species are quite common around Melbourne. People all over the world mistake crane flies for extremely large mosquitoes, when in fact they are mosquito predators (commonly known as ‘Mosquito Hawks’ in other countries).

These are good insects that will not bite you and that you want to have around your house. Spiders are also your friends – if you are comfortable having spiders around your house they will certainly help.

Then you have chironomids, which to the untrained eye look very much like mosquitoes but aren’t all that closely related. Their common name – the non-biting midge – is a bit of a clue as to why you don’t need to worry about them. Chironomids, like mosquitoes, breed in standing water and can form huge mating swarms.

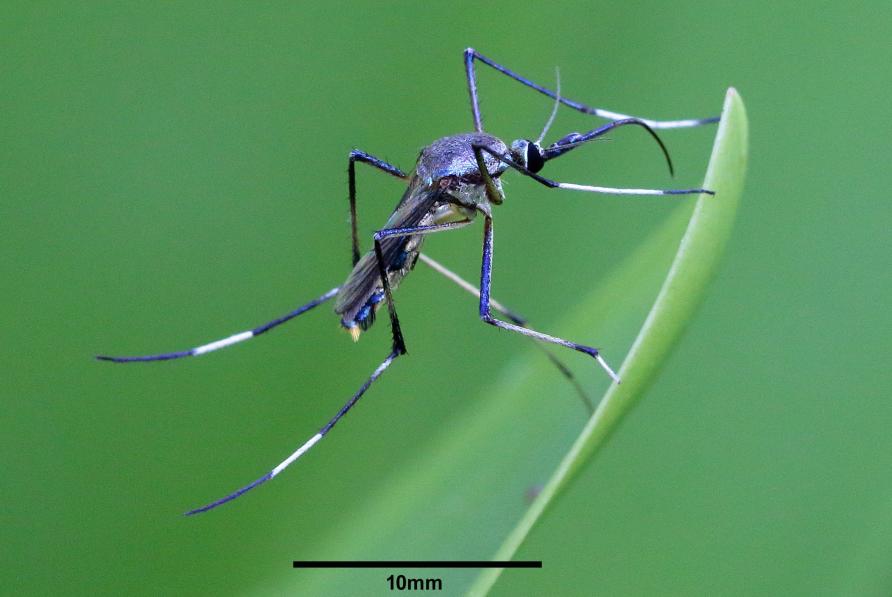

Some ‘giant’ mosquitoes like Toxorhynchites speciosus, which can reach over 12 millimetres in size, don’t bite humans. In fact, as adults, they are strictly vegetarian. Even better, their larvae (wrigglers) are predatory, eating other mosquito larvae, so these are another natural ally in your struggle against mosquitoes.

So, in general, the size of a mosquito shouldn’t worry you. Although many species of mosquito don’t bite humans at all, it’s still best to avoid them wherever you can, just in case.

Q) What can we do about them?

The most effective strategies are quite straightforward – avoid being outdoors at dusk and dawn when the human biting species are most active

Wear long-sleeved shirts and long pants. Make sure to use mosquito repellent if you are outdoors, and don’t forget to reapply if you’ve exercised, gone for a swim or have worn it for a couple of hours.

On your property, do your best to get rid of potential breeding sites – anything can hold standing water.

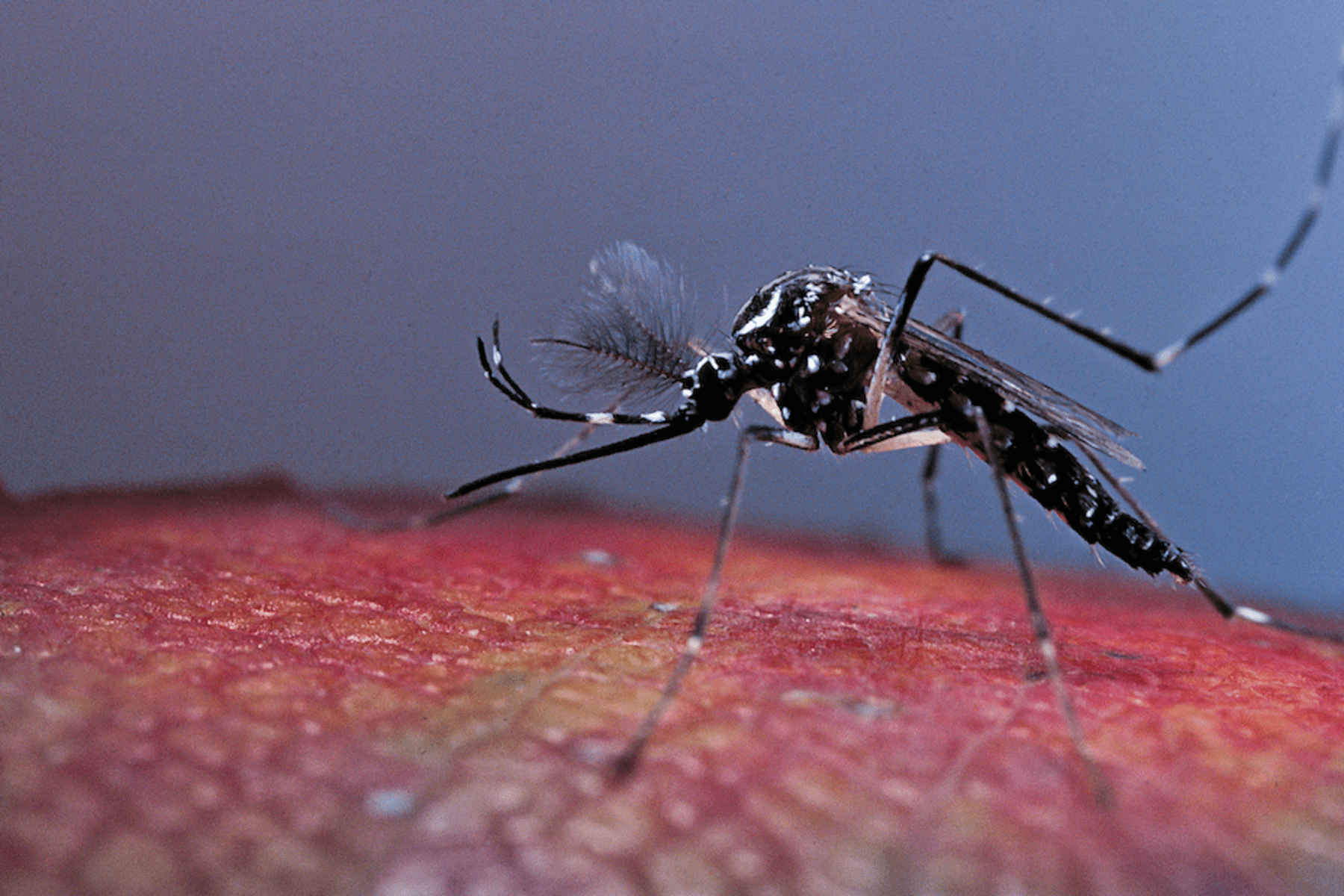

Some mozzies, like the common pest Aedes notoscriptus, will happily breed in very small amounts of water, so even the drip trays under your plants are a potential breeding site.

This species can transmit viruses like the Ross River Virus and is also the prime suspect involved in the transmission of the bacterium that causes Buruli ulcer.

To make sure you avoid breeding mosquitoes in your garden, remove any garbage on your property like old tins, tires and buckets and empty out all containers (like drip trays under potted plants) after it has rained.

Here’s more than 100 Aedes notoscriptus (the Australian Backyard mosquito) we collected in one hour last weekend. Picture: Supplied

Here’s more than 100 Aedes notoscriptus (the Australian Backyard mosquito) we collected in one hour last weekend. Picture: SuppliedAlso make sure that you keep your gutters clean, and ensure that pipes and screens around your water tanks are intact, repair or replace them if they are not.

Anything that can hold water is a potential breeding site, so if you have a water tank, make sure mosquitoes cannot get in and lay eggs. Old septic tanks are also a common breeding site, so if you live in the country or on the outskirts, make sure that these are properly filled in.

You can also purchase granular products (“insect growth regulators”) to add to standing water that cannot be emptied easily.

With climate change presenting more variable conditions including more intense rain periods, it’s inevitable that periods when mosquitoes become problematic will increase in frequency.

And areas that previously did not experience so many mosquitoes might see explosive events like we are seeing presently.

Moreover, changes in the distribution of mosquito vectors and hosts that carry diseases mean that diseases are likely to crop up in new areas. We have already seen the recent outbreak of Japanese Encephalitis (JEV) in Australia, which was likely bought over by migratory water birds.

Culex annulirostris is one of the mosquito species that can transmit JEV. This species can breed in urban areas but also in natural habitats including bushland and wetland.

It’s difficult to accurately unpack the range of impacts we can expect from climate change, but we do have some examples of mosquito species changing their range in a way that is consistent with climate change.

A key example of this is the Tiger Mosquito (Aedes albopictus), which recently shifted its range of habitation exclusively from the tropics and subtropics to now having invaded most of Europe as conditions warm and the species seems to evolve to handle cooler conditions.

Tiger mosquitoes are currently found in the Torres Strait but have not yet established on mainland Australia.

So, yes, parts of Australia are seeing a surge in the number of mosquitoes this spring, and we’re likely to see more springs like this one as the real impacts of climate change kick in.