repliCATS: Responding to the Replication Crisis in Science

An interdisciplinary team of researchers across the School of Biosciences and SHAPS are working together to address one of the most pressing controversies of modern science – scientific replicability. The repliCATS project, based predominantly at the University of Melbourne, is among the first of its kind to be funded by end users of scientific research. Dang Nguyen spoke to Fallon Mody, a research fellow at repliCATS, about the project and its approach to combating the replication crisis in science.

Could you tell us about the concept of ‘replicability’ and why it is important?

Essentially, a well-documented piece of research should give you enough information to replicate it – in other words, to repeat it and to end up with roughly the same results. When we say that a research finding is replicable, we mean that if you were to independently repeat the study, using the same methodological and/or analytical approach documented in the original research, then you should be likely to obtain similar results.

Replicability is one of the cornerstones upon which credibility and reliability in scientific research is built. A well-designed study should replicate! And if a study cannot be independently replicated, then its findings are less reliable.

It is clear that replicability is very important to good science. What are the major issues with replicability in science today?

What lots of scientists have been worried about for many years now is that high-profile replication efforts have reported alarmingly low rates of replicability. For example, one study reported that only 13 out of 21 studies of high-profile research published in Nature and Science could be replicated.

There are many reasons a study might not replicate, including: lack of transparency in how research is reported; researcher bias; mistakes made by researchers; the ‘publish or perish’ culture academics work in, which leads researchers to engage in questionable research practices; or even outright fraud.

For the purpose of talking about our project, however, you can hopefully see how low replication rates in published research has huge implications for lots of people – from current and future researchers to end users of science, like policy makers.

At the moment the only way to be certain of a reported result is to repeat a study entirely first, which is just not feasible. On average, a replication takes months to complete and, in some cases, a reported average of US$27,000 per experiment!

So scientific replication is both time-consuming and expensive. Is there any way we could predict reliability systematically and confidently?

This is what the repliCATS project team is funded to test!

We aim to crowdsource predictions about the replicability of 3000 research claims in the social and behavioural sciences, including criminology, experimental economics, education, marketing, and psychology.

The repliCATS project is part of a wider research program called SCORE, sponsored by the U.S. Department of Defense (DARPA). This program is, as far as we know, the first time that such a large research program investigating replicability has been funded by end users of scientific research.

The most ambitious bit about SCORE is that its eventual goal is to see if we can train Artificial Intelligence to read and compute a confidence score for a piece of research!

That sounds very exciting. What method are you using for this project, and how does it compare to other methods?

We plan to use a method called the IDEA protocol – developed at the University of Melbourne – to collect predictions for these 3000 claims.

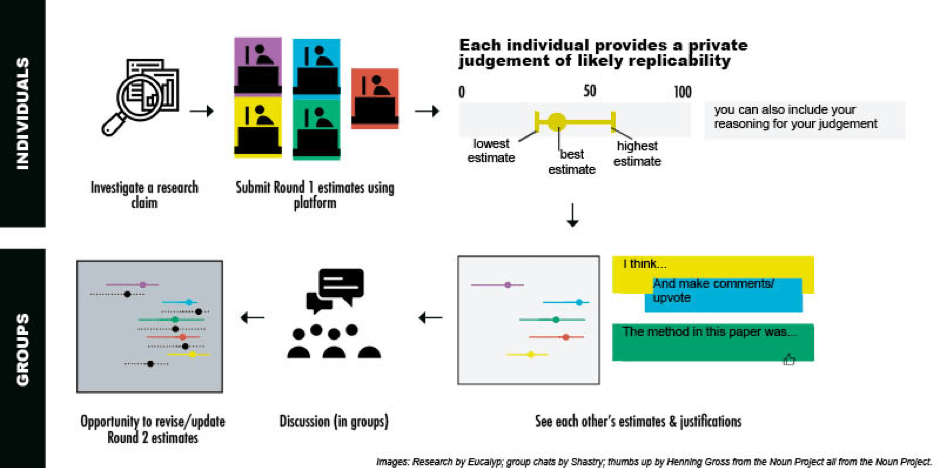

IDEA stands for Investigate, Discuss, Estimate, Aggregate. The figure below summarises the steps in the IDEA protocol as we use it in this project.

Essentially, we recruit diverse groups of people who then go through a stepped process: they make a private judgement after reading a research claim, they then get to see and discuss each other’s judgements. Finally, they have the opportunity to update or revise their first round judgement (if they want).

The IDEA protocol has proved particularly useful for making predictions about uncertain events, and draws on prior research that has found that groups usually perform better than or as well as perceived experts.

Our method is inspired by the growing Open Science movement around the world, which calls for transparency of not just research results but also research methods. We are constantly in dialogue with scientists outside of Australia who are advocating for the same cause. Earlier this year, for example, we were able to invite Brian Nosek – co-Founder and Executive Director of the Center for Open Science and Professor at University of Virginia to give a public lecture as part of the 2019 SHAPS ‘Walls’ Public Lecture Series. In true spirit of openness, lecture slides and audio-recording from the lecture are made available to all via ABC’s Radio National.

What’s it like working in such a large interdisciplinary team?

Unique! It is a unique experience. Our team has ecologists, engineers, historians, mathematicians, philosophers of science, and psychologists in it. We have lots of arguments about the meaning of words and numbers!

Where can we find out more about the outcomes of the project, or potentially get involved in some way?

We’d love for you to participate in repliCATS! If you have completed or are completing a relevant undergraduate degree, over 18 years of age, and interested in making judgements about replicability, please get in touch with us. You can express interest using this form, or just email repliCATS-project@unimelb.edu.au so we can get back to you.

You can also visit our website or follow us on Twitter @repliCATS