On Studying Chinese History in Melbourne: An Interview with Dr Xavier Ma

In 2017 Xavier Ma became the first postgraduate from the People’s Republic of China to receive a PhD in History from the University of Melbourne. Xavier came to Melbourne in 2013 on a scholarship targeting graduates of Peking University. During his candidature, he distinguished himself by winning a D. Kim Foundation Fellowship to support him in the writing-up stages. Upon graduating, he was awarded a postdoctoral fellowship at Tsinghua University. Current History PhD candidate Sofie Onorato had a conversation with Xavier about his research, his career, and his time in Melbourne.

When did you first develop an interest in history, and at what point did you decide to pursue it as a career?

It was at the beginning of my college years. I decided to major in World History and Sociology, because they looked fun and, thank god, they did not really require any substantial mathematics courses, at least at that time. I went into the graduate school at Peking University in 2010. During my graduate years there, I met great teachers and good friends, and I started to think that being a historian might not be a bad thing. As I was graduating in 2013, I decided to do a PhD and, luckily, I got the scholarship from University of Melbourne.

You are currently doing postdoctoral research in China. What does this kind of position involve, and can you explain your topic a little for us?

I’m now in the Department of the History of Science at Tsinghua University. It’s a new department, established only in 2017. It has an ambition to build the first real Science Museum in China (China has lots of scientific centres, but no museums as yet). So currently, a lot of the department’s work is focused on preparing for founding this museum. We hope to have it built up by 2021. I’m helping out with the museum and, at the same time, completing a project sponsored by the university.

What are you aiming to achieve with this project?

This project is a chronicle of the development of scientific and technological disciplines at the university, under contract with the University press. It should be published once completed.

You recently submitted your PhD at the University of Melbourne looking at Chinese territory, mining and mineral science from the mid-nineteenth to mid-twentieth century. What first sparked your interest in the relationship between nationhood and industry, and why this period?

My topic fell into more the history of ideas than the history of industry. I changed my topic several times during the first year of my PhD. I started up with a totally different topic, tourism in twentieth-century China, but my supervisor, Professor Antonia Finnane, and I soon realized it was not as do-able as I originally thought. Then I fell into a period of not knowing what to do for a while, before I got interested in mining.

Initially I was looking at mining from the perspective of the history of economics and industry, but soon I found some undiscovered intellectual and conceptual significance in the topic. I began to reflect on the fact that our common understandings of mining, minerals, resources, industry, and many other terms and concepts in historical writing might have totally different implications in pre-modern times and non-Western contexts. Then I turned to explore what minerals and mining actually meant in pre-modern China, and how the meanings changed through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The changes were primarily defined by science from other countries and by the international contests for raw materials during this period. This context and the dichotomy between ‘us’ – in this case, China – and others meant that this knowledge became associated with China’s nationhood.

Was there anything unexpected that you uncovered in your research?

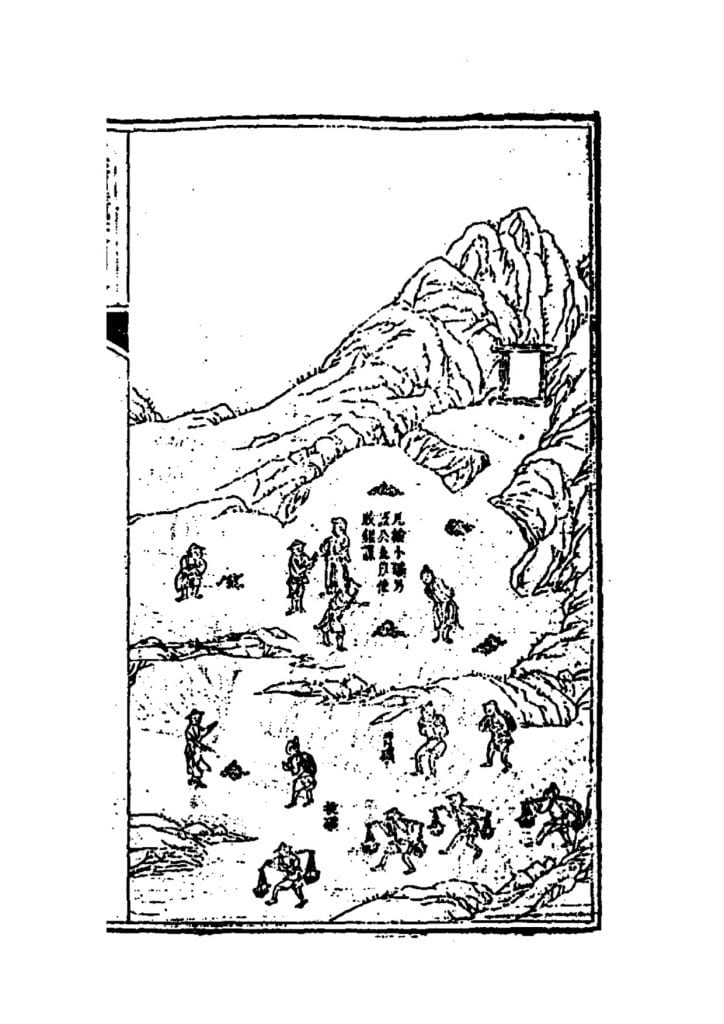

Yes. One of my chapters is about the miner’s body – how it was represented and perceived in texts and images. I examined technical texts and stories on mining and miners from the late Qing to the Republican period and found that technological knowledge, Marxist ideologies and nationalism were important factors shaping the representation of miners and their tools and working bodies. This is something I didn’t expect when I started working on this topic.

Why is it important to understand the history of nation-building and nationhood today?

I’m not an expert on politics, but I think the nation-state is still one of the key factors defining a state’s role as well as a person’s identity, especially in non-Western countries, where the whole idea of the nation-state must be seen as the legacy of global colonialism. Understanding it may help us understand where we’ve come from, where our dilemmas lie now, and where we can go from here.

How did studying Chinese history in Australia influence or challenge your approach to your historical research?

The best thing I had in Australia is probably my supervisors, Professor Antonia Finnane and Dr Simon Creak, and committee chair, Dr Gerhard Wiesenfeldt. All three were from different backgrounds – in Chinese history, southeast Asian history, and the history of science. Their expertise in different aspects made it possible for me to have a broad perspective on what I had to do and what I could do.

Another important thing is Australia’s colonial legacy and the way Australians reflect on it. While I was studying at Melbourne, I often heard diverse voices in the interpretation of history. These voices, sometimes conflicting with each other, actually made me think about Chinese history as something rich and unstable that can never be monopolised by anyone.

What was a highlight of your degree? What do you miss most about your time at the University of Melbourne?

I have to say I really miss the people in SHAPS. I benefited a lot from the department, from the professors, the cohort, and friends. And, of course, my supervisors.

What advice would you give to incoming postgraduate researchers?

Always prepare to publish! I guess that’s the lesson I learned from my experience. As I was trying to find a job, I realised that most Chinese universities require PhD candidates to publish at least one article before they are awarded the degree. As far as I know, Australian universities, including Melbourne, do not require this, especially for students of the Humanities. Although students from different universities may produce theses of the same quality, articles always give you an advantage when it comes to job hunting.

Name a text or scholar that has shaped your practice as a historian.

Edward Said and his Orientalism. My education and knowledge of history before college were all submerged in the Marxist historiography, especially my understandings of colonialism, imperialism and the history of the nineteenth century. They were all dominated by Lenin’s interpretation, until I encountered Said and his work, as well as other post-colonialism theorists. Of course, they had been there for decades already, but they were all new to me. They opened a new door for me to see modern history and to evaluate the historical and contemporary connection between China and colonialism.