Researching History on the High Seas

Last year, History of Science lecturer Dr Gerhard Wiesenfeldt sailed across the South Atlantic on a tall ship. During the six-week voyage, he explored the use of early navigational instruments including the cross-staff and astrolabe. In the following interview, Gerhard describes this unique experience to Samara Greenwood.

Could you give us a brief overview of your recent voyage? What was your motivation for the trip?

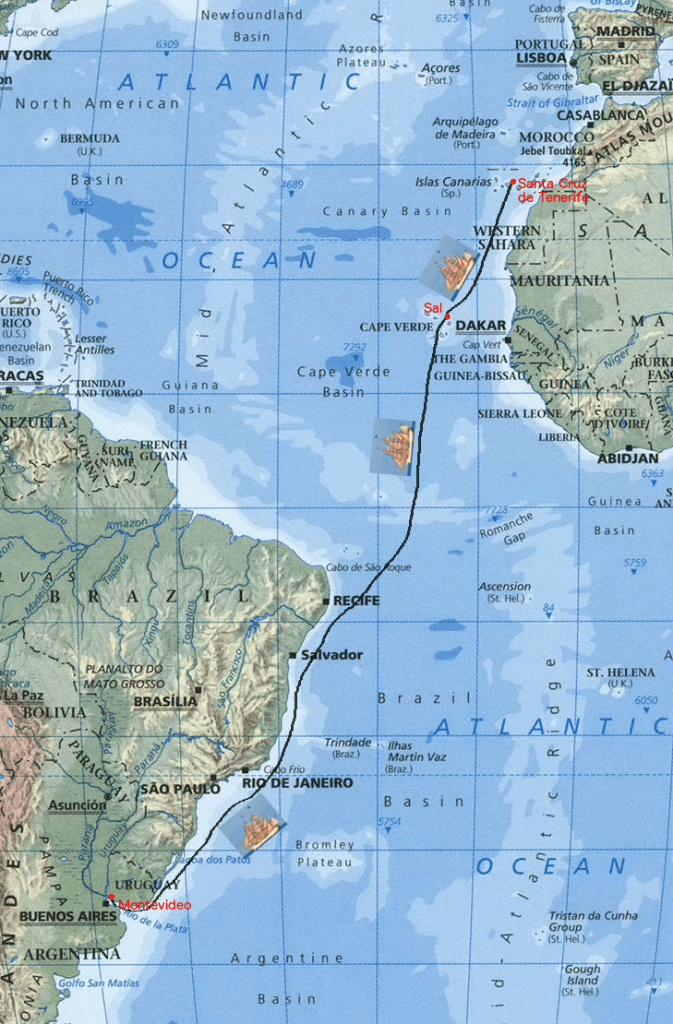

My original motivation had nothing to do with scholarly research. I’ve done a fair bit of tall ship sailing over the past years, so when I was up for long service leave last year, I booked myself on a longer voyage of six weeks. We crossed the Atlantic from Tenerife to Montevideo, with a stopover in Cape Verde.

However, since my main research is on the relation between practical knowledge and academic philosophy, and I use replica instruments for teaching, I decided to combine both interests and try out historical navigation techniques while on board. I used three different astronomical instruments: an astrolabe, a cross-staff and a kamal. All these instruments were used to measure the angle between the horizon and a star (or the sun) to help determine your position, especially the latitude you were on.

While some people have done similar projects, I seem to be the first one to do this in the tropics. The tropics hold a particular problem for observations; at midday the sun is so high it is very hard to observe precisely. This places obstacles on what was otherwise the main recommended method for navigation.

I understand you had some of the instruments made specially. What did that involve?

I was very lucky as I prepared my voyage in Brunswick (Germany), one of the few places in the world that still has an active wainwright – i.e., a specialist in historical wooden tools. His knowledge about wood was very helpful in building the cross-staff in particular.

Did the trip achieve what you hoped it would?

It started out as a ‘fun’ project without specific expectations. Yet, while doing the project, I noticed I learned a lot – not just about navigation – but about the relationship between early modern science and practical knowledge.

Usually when we think about the application of scientific knowledge, we think of it as a one-way transfer. In using a cross-staff for navigation I’ve learned there is a problem with this model – astronomers first needed to learn how navigation was done to then provide the data needed for the most reliable form of navigation. It surprised me this took more than a century, even though navigation had become crucial for the European colonial enterprises.

You mentioned that prior to the invention of navigational instruments, sailors would navigate by reading the environment. What did that involve?

There are different methods, mostly related to reading ocean swells and the weather, to gain information about your position, possible land close by or potential weather changes.

You can describe all these methods – and the early forms of celestial navigation I’ve been practicing – as reading different signs and trying to bring these readings into a consistent inference of your location. In general, the more signs you can bring together, the better your result should be, so it was undoubtedly an improvement of navigation.

Later on, celestial navigation became dominant, especially very recently with the introduction of GPS. Other methods then tended to be either less valued or were completely neglected. This can produce problems when the dominant technology fails, and you need to go back to earlier methods of navigation. I’ve noticed even the US navy has realised this is a problem.

History doesn’t typically seem like a ‘hands-on’ enterprise, what do you feel is gained by experiencing historical practices firsthand? Were you inspired by other similar research?

I’ve been close to colleagues who have done research via replicating historical experiments in physics, originally for teaching purposes. I’ve also used these methods in teaching history of science quite a lot.

While I am fairly critical of claims that we can gain first-hand historical knowledge by a hands-on approach, on such a project you ask different questions about the historical material you encounter. I certainly read seventeenth-century navigation manuals now with a very different perspective than I did before my voyage.

What are your next steps with this research? How would you like to take it further?

There are two avenues I’m pursuing. One is a collaboration with colleagues in anthropology and organisation studies on how certain types of navigation relate to specific cultural forms and knowledge economies.

The other one brings me back to my original research on the relation between practical knowledge and academic philosophy. I was struck by the similarity between seventeenth-century navigation treatises and modern science textbooks – for instance, in the use of examples and exercise questions. While there has been good literature about the rise of informal and semi-formal teaching methods in science, there might be a story to tell about how natural philosophers in the eighteenth century learned these methods from practitioners.

Gerhard coordinates the first-year subject Science and Pseudoscience, second-year subjects Electricity: An Experimental History and summer intensive Astronomy in World History, as well as the third-year subject Magic, Reason, New Worlds 1450–1750.