Were These the Good Old Days? The 1919 Flu Pandemic in Australia

As we watch the global COVID-19 pandemic unfold, some scholars are looking back to the history of the worldwide influenza pandemic of 1918 to 1920. Mary Sheehan, PhD student in SHAPS, discusses the experience of those events 100 years ago in Australia, in this blog post, republished from Living Histories.

Watching the rapid spread of the Coronavirus today seems like a re-enactment of events a century ago. But then too, many things were very different in 1919 when the ‘Spanish’ influenza virus arrived in Australia. The nation was recovering from war, nothing was known about viruses, no central health authority existed to co-ordinate a response, authority was divided between the government and local councils at State level, and antibiotics had yet to be developed. Harder still, no international bodies existed to offer global warnings or provide advice, for those in Versailles were still nutting out plans for a League of Nations and the World Health Organization (WHO) was years away from being formed.

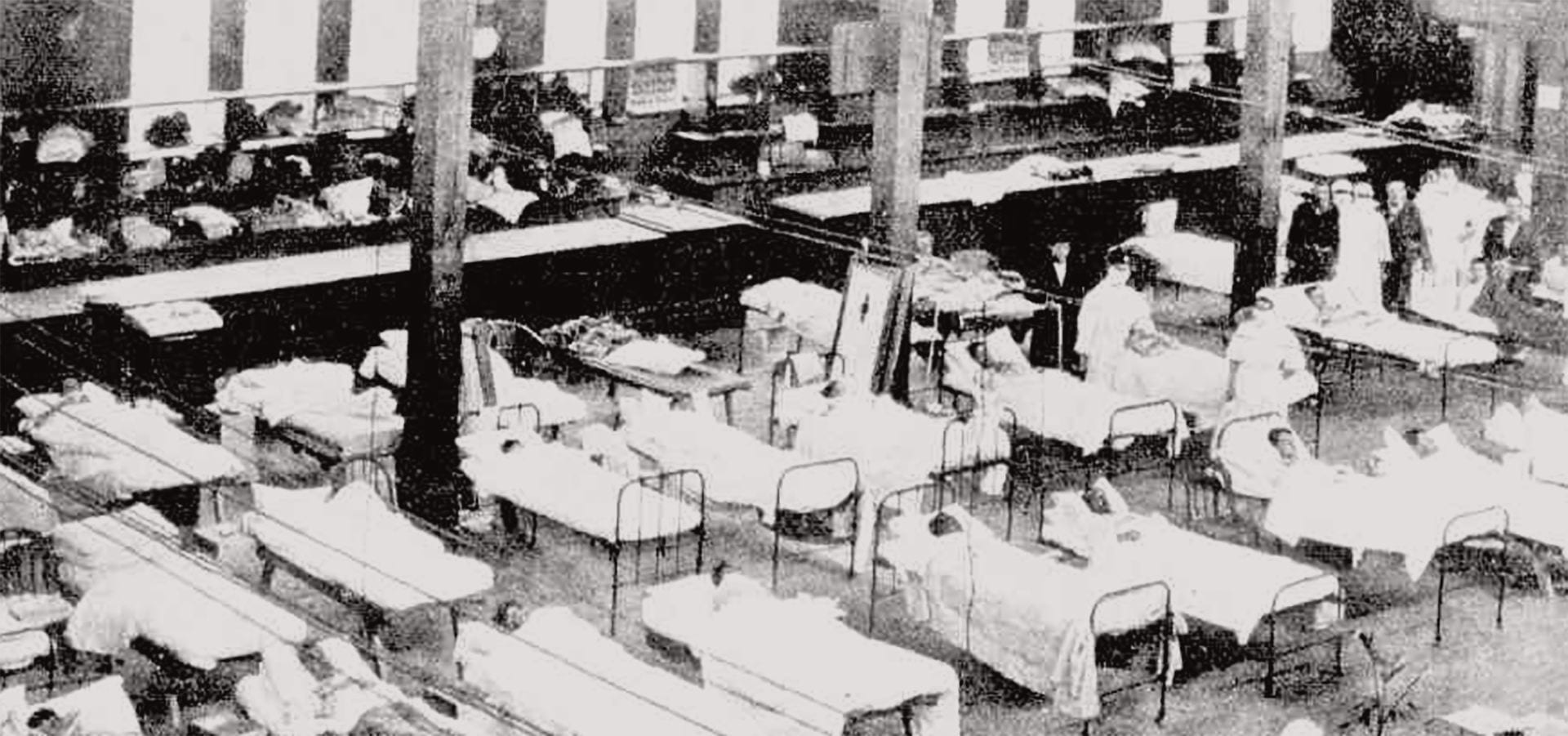

When ‘Spanish’ flu arrived in Melbourne a little more than 100 years ago in January 1919, there were not enough hospital beds to accommodate the sick, so emergency hospitals had to be created. The largest emergency accommodation was set up in Carlton’s Exhibition Building in early February 1919 and operated until September. More than 4,000 patients were treated there and, a credit to the medical and nursing staff, the mortality rate was around ten percent and lower than in some of the major hospitals.

Because schools had been closed, other emergency hospitals were created in these buildings in suburbs like Richmond, Collingwood, and Armadale. The Williamstown Naval Depot, army base hospitals in St Kilda Road and at Broadmeadows were also used, as was the recently opened Footscray Technical College. Thirty-four emergency hospitals were created in addition to the established public hospitals and the infectious diseases hospital at Fairfield admitting the sick.

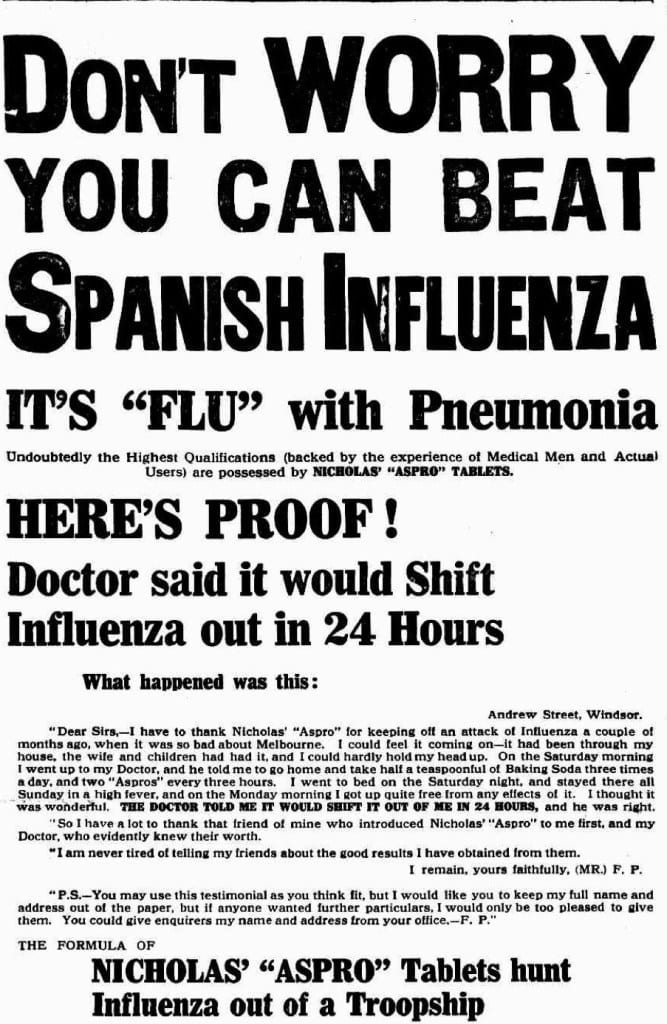

Advertisements without official approval from health authorities were banned after false claims and promises had been made about the efficacy of products. Although panic arose as people rushed vaccination centres, erroneously believing injections would afford protection from the virus, no evidence has been found of panic buying, since limited reserves prevented individuals from stockpiling goods. Yet, despite their limited means, there was much altruism evident in this tinier postwar society, as local suburban women’s groups formed and developed rosters to prepare food and visit the sick – households would put an SOS sign in their window to show help was needed.

Borders were closed and people quarantined in tents where they waited out their time (between 4–7 days) before gaining permission to cross. Others were stranded in Melbourne without transport when trains were unable to travel interstate and shipping agents required evidence of quarantine. Many had run out of funds and were destitute. Picture theatres were also banned from opening, hotels were only allowed a maximum of 20 patrons at a time, and race meetings were called off. As a result, thousands were thrown out of work and had to seek relief from their local council.

By September the virus had run its course. Although the memory of those who did not survive lived on in the hearts of their loved ones, public memory soon forgot the episode as attention was turned to honouring the war dead and the process of recovery.

Still, Melbourne and the nation were more fortunate than other places in the world where mortality was extraordinarily high for an estimated 15,000 died in Australia – the death rate globally was more than 50 million. That the nation experienced lower mortality rates was the result of strict maritime quarantine controls implemented the previous year in October 1918. This delayed and reduced the impact of the disease. Nevertheless, as occurred throughout the world, deaths from the virus were mainly among those aged 20 to 40 years, and mostly males, a loss the nation could ill-afford to bear on the heels of war losses.

Mary Sheehan is a professional historian who is currently undertaking a PhD in SHAPS on the 1919 Spanish flu pandemic in Melbourne. She has worked in heritage, undertaken oral history projects, and completed multiple commissioned histories. She also has a nursing background.