Race, Change and Time in the USA

Americans are reaching back into history to try to understand why progress on racial equality has been so heartbreakingly slow. In this article, republished from Pursuit, Professor David Goodman explores the question.

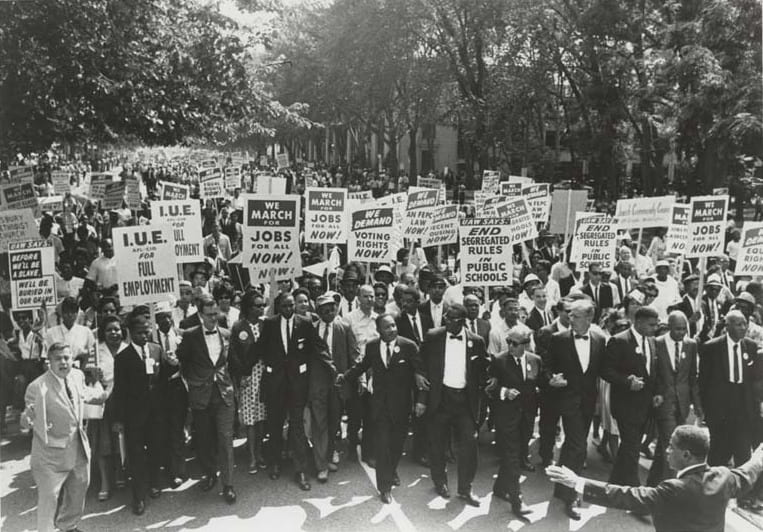

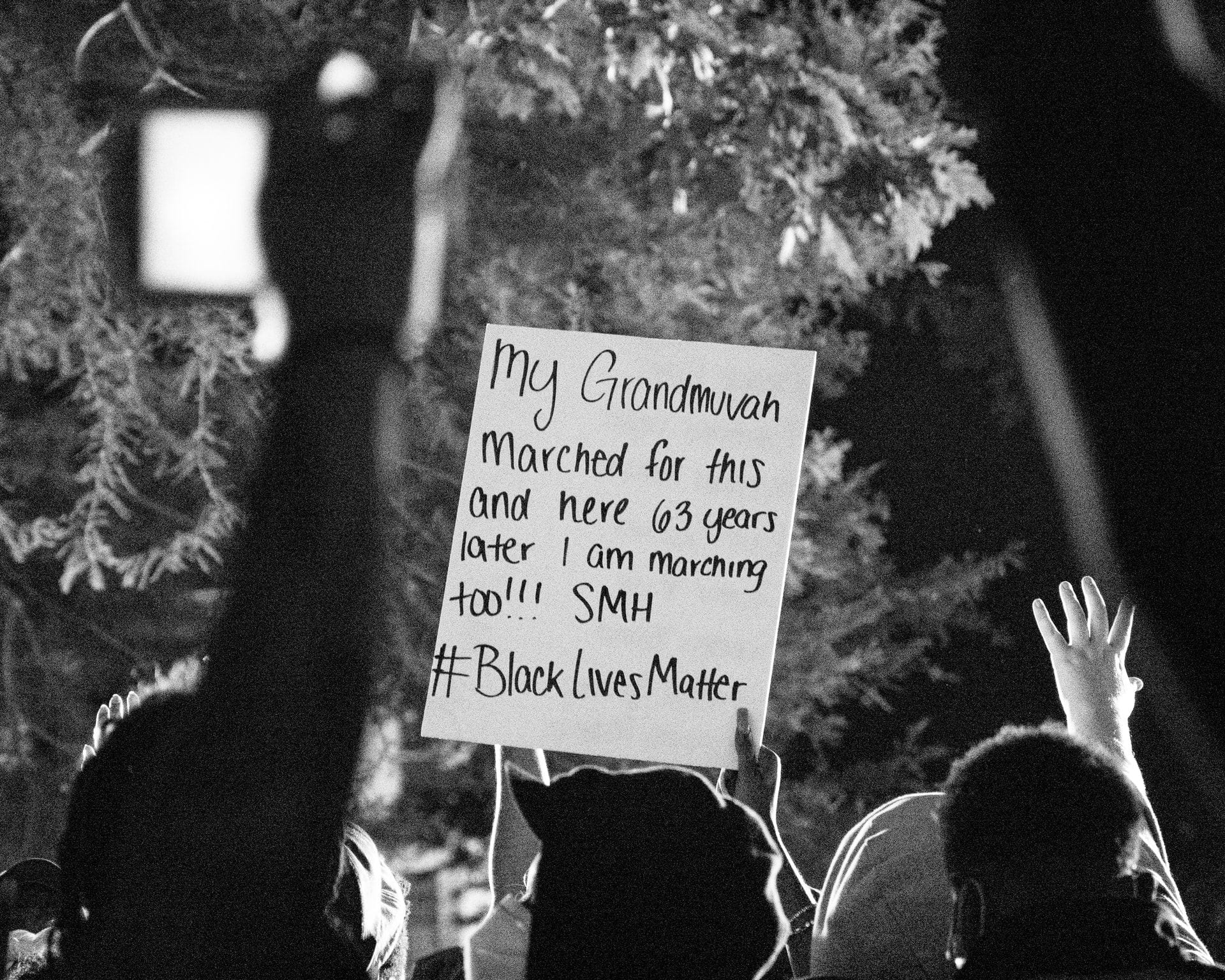

Many commentators have compared or rejected comparison between the current public protests sparked by the death of George Floyd in the USA and the uprisings of 1968 – the riots in a hundred cities in response to the assassination of Martin Luther King and the realisation that formal civil rights victories hadn’t ended racial injustice and inequality in the USA.

The comparisons between now and the late 1960s go to the heart of the question of why progress on racial justice in America has been so elusive.

President Donald Trump’s responses referenced the late 1960s too, when he deployed the phrase “when the looting starts, the shooting starts”’. It was originally used by Miami police chief Walter Headley in 1967 and segregationist George Wallace in 1968.

There were more than 150 ‘race riots’ in the United States between 1965 and 1968, mirroring the violence inflicted by white Southerners on civil rights activists. The riots clustered in cities in which black income was falling and resulted in steep, localised, falls in property values.

When Dr King spoke at Grosse Pointe high school in white suburban Detroit on 14 March 1968, he condemned violence but insisted that riots were “the language of the unheard”, an understandable response to injustice.

Dr King’s speech came just two weeks after the release of the Kerner Commission on Civil Disorders, which famously concluded that the United States was “moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal”.

Half a century on, as the increasingly diverse USA heads towards a majority of the population being ‘minorities’, those words describe an aspect of American society seemingly still resistant to change.

Celebrating Martin Luther King and civil rights as milestones of national progress sits comfortably with nationalist narratives. But statistics on racial disparities, carefully collected since the civil rights era, tell a different story.

The black-white wealth gap has increased sharply since the global financial crisis of 2007–8. In 2017, the median household income among non-Hispanic whites was US$68,145, compared with that for Hispanics (any race) at US$50,486 and for African Americans at US$S40,258.

Residential segregation by race is declining a little but remains remarkably persistent. Relatedly, in education there is segregation by school but also within schools. For example there is differential access to advanced placement and gifted programs, and black students are 3.9 times more likely to be suspended from school than white students.

In policing and justice, the differences are stark.

African Americans and Hispanics make up approximately 32 per cent of the US population but in 2015 comprised 56 per cent of all incarcerated people. The USA has the highest incarceration rate in the world and African-Americans are more than five times more likely to be incarcerated than whites. That gap is decreasing but only slowly.

Between 2013 and 2019, police killed 7666 Americans, but African Americans were three times more likely than whites to be killed by police.

There is little correlation between the incidence of violent crime and rates of police violence. Rather, the militarisation of policing since the 1980s War on Drugs seems to be one of the main causes.

Majorities of both black and white Americans say blacks are treated less fairly than whites by the police and criminal justice system.

Hopes that the election of the first black president signalled the USA’s coming of age as a post-racial society now seem far away.

Tragic asymmetries of perception remain. In late 2018, 43 per cent of white Americans didn’t think that racism against blacks was widespread, but only 16 per cent of black people shared that view.

Americans are more pessimistic about race relations than they were earlier this century. In the period 2001 to 2013, about 70 per cent of non-Hispanic whites and 60 per cent of African Americans thought race relations were ‘very good’ or ‘somewhat good’. By 2018 that had declined to 54 per cent for whites and 40 percent for blacks.

The Trump presidency responded to, and in turn exacerbated, that decline in optimism about race relations.

Americans are, not surprisingly, conflicted and divided on the question of whether change is likely. In late 2018, 38 per cent of white people and 53 per cent of black people thought that black-white relations “will always be a problem” for the United States; while 58 per cent and 44 per cent respectively thought that they would be “eventually worked out”.

While fewer Americans hold to the overtly white supremacist and racist views common in the past, inequality persists; scholars have been attempting to formulate explanations for how there can be “racism without racists”.

At Grosse Pointe in 1968, Dr King criticised the idea that only the passage of time would eliminate racial injustice, arguing instead that “time is neutral.”

“Human progress never rolls in on the wheels of inevitability, it comes through the tireless efforts and the persistent work of dedicated individuals … we must always help time”.

The true solution to violence he said was justice.

“Our nation’s summers of riots are caused by our nation’s winters of delay. And as long as America postpones justice, we stand in the position of having these recurrences of violence and riots over and over again”.

Last week in his eulogy for George Floyd, the Reverend Al Sharpton also reflected on time and racial justice in America.

He told a story about stasis, alluding to the 1619 arrival of the first enslaved Africans in Virginia and to George Floyd’s death by asphyxiation with a policeman’s knee on his neck.

“George Floyd’s story has been the story of black folks. Because ever since four hundred and one years ago, the reason we could never be who we wanted and dreamed of being is that you kept your knee on our neck”.

After elaboration of that “over and over again” theme, Reverend Sharpton shifted key to a different narrative about time.

“When I looked… and saw marches where in some cases young whites outnumbered the blacks marching, I know that it’s a different time and a different season”.

Recalling a time when he forgot to adjust his watch at the end of summer and was left running late for an appointment, Reverend Sharpton addressed President Trump (the “bible-carrying guy … sitting in Washington, talking about militarising the country”), saying “you can get on the TV but you’re on the wrong time”.

He then went on to broaden his comment, saying, “you all don’t know what time it is. You all operating like it’s yesterday”.

Confronting recent events and the record on race sketched above, African American leaders have remarkably once again found their way this past week to a narrative of hope and change.

Rally organisers in many cities played A Change is Gonna Come, the 1963 protest anthem by American singer Sam Cooke. Radio stations nationwide will play it at 3pm on June 9th to coincide with George Floyd being laid to rest in Houston. On the YouTube page of the song, hundreds liked the comment “come here in tears after what happened today to George Floyd”.

District of Columbia mayor Muriel Bowser tweeted: “It has been a long time coming, but I know. I know – change will come” with a clip playing the song.

How will change come? Remarkably, the city council of Minneapolis has just voted to disband its police department. Reform of police forces around the country seems possible in a way it didn’t just a few weeks ago.

But most calls for change end in reminders about voting. Stacey Abrams, founder of the voting rights group Fair Fight Action, wrote last week that, even at a time of “enormous cultural change”, meaningful change has to start with voting, a “long and complex … tedious but vital” process.

Former president Barack Obama also emphasised the work ahead and the need to look beyond Donald Trump’s distractions.

Reminding Americans to vote, the former president wrote: “a lot of us focus only on the presidency and the federal government. And yes, we should be fighting to make sure that we have a president, a Congress, a US Justice Department, and a federal judiciary that actually recognise the ongoing, corrosive role that racism plays in our society.

“But the elected officials who matter most in reforming police departments and the criminal justice system work at the state and local levels … Unfortunately, voter turnout in these local races is usually pitifully low”.

At a time when attention, nationally and internationally, is more than ever fixated on the presidency, and when local news is an endangered species, it was a quiet reminder of Dr King’s point: “we must always help time”.