Episode 5 in the SHAPS Podcast Series: Professor Peter McPhee

Statues, Heritage and the French Revolution

Societies have always used statues and other monuments as ways of recognising power and eminence. In Australia, as in many other places, there is currently public debate over whether some statues should be removed, who should make the decision, and what should be the fate of the statues themselves. Should they be displayed with explanatory plaques, taken away to be preserved in museums or simply removed? Such debates are common in history. In this episode, Professor Peter McPhee surveys the wide range of objects destroyed during the French Revolution – from buildings and statues to books and paintings – but also the remarkable responses of revolutionary governments. It concludes with some reflections about the place of monumental statues and heritage sites in Australia.

Listen on the player below or on your favourite podcast platform.

Transcript

This podcast comes at a time of impassioned debate about the role and place of public monuments. As part of a wave of earnest protests against systemic racism unfolding across the world, statues and other monuments have become the focus of renewed critical debate about the public function of the past. At the same time, corporate destruction of timeless Aboriginal sites in Australia has horrified the world. This is a moment of public reckoning against systemic inequality whose tenor is only heightened by the COVID-19 pandemic, which continues apace.

Today, we are delighted to welcome the distinguished historian of the French Revolution, Emeritus Professor Peter McPhee to offer some historical perspective on the connections between monumental heritage, power, and change.

Societies have always used statues and other monuments and signs as ways of recognising power and eminence. Civic symbols matter. As appropriations of public space to make claims about the meaning of the past, statues are often a focus of contestation, as in contemporary Australia. Here, as everywhere else, there is public debate over whether statues should be removed; which ones, who should make the decision, and what should be the fate of the statues themselves. Should they be displayed with explanatory plaques, taken away to be preserved in museums, or simply removed?

At heightened times of tension, such as the Black Lives Matter protests in the United States, and their reverberations in countries like ours with parallel issues, it is not surprising that specific monuments are a focus of public controversy.

Even more so in times of revolutionary change, the legitimacy of particular statues can become the focus of collective, iconoclastic action. Let me take as an example revolutionary New York during the War of Independence in 1776. In colonial New York, statues of King George III and Prime Minister William Pitt had been erected in 1770, recognising their role in the withdrawal of the 1765 Stamp Act, hated by the colonists as an example of ‘taxation without representation’. By the time they were erected, however, further measures had been taken by Britain to impose taxes and military control on its North American colonies.

After the Declaration of Independence in 1776, the statue of George was pulled down by self-styled ‘patriots’. It was reported that the leaden statue would be melted down to create bullets for the war with Britain, which had just broken out. But not all of the statue was so used. His head was removed as an act of symbolic beheading, recalling the execution of Charles I in 1649. Loyalists – locals who were loyal to England – were subsequently able to regain the head and send it back to England. Other pieces were hidden and reappeared later: for example, the tail of the King’s horse survived and is displayed in the New York Historical Society today.

This statue of William Pitt was commissioned similarly to commemorate the English statesman who had lobbied Parliament successfully for the repeal of the Stamp Act. After the British army took possession of New York City in the autumn of 1776, however, vindictive British soldiers decapitated the statue of a politician seen as the friend of the colonists and broke off his arms.

Revolutionary iconoclasm was far more explosive in France after 1789, when revolutionaries set about transforming every dimension of public life. In this presentation I want to survey not only the range of objects destroyed – from buildings and statues to books and paintings – but also the range of responses of revolutionary governments. I will conclude with some brief reflections on the current debates about the place of monumental statues and heritage sites in our own society.

So important was the action of Parisian working people in July 1789 in seizing the massive Bastille fortress that dominated the popular neighbourhoods, that the new National Assembly – France’s first – decided to let out a contract for its demolition. The physical destruction of the Bastille would symbolise that the absolutism of the Old Régime and arbitrary punishment were gone. The successful tenderer for the demolition was Pierre-François Palloy, soon nicknamed ‘Patriote’ for his zeal. Palloy himself was the great beneficiary, making a fortune from organising guided tours and selling off the stonework as carved statuettes and medals. Each of the 83 new administrative departments across the country received a free carving of the Bastille made from one of its foundation stones.

Aware of the rupture in the nature of government and administration achieved in 1789, the National Assembly decided on 12 September 1790 to create the Archives Nationales, the National Archives, quote: “the repository of all the acts which establish the Constitution of the Kingdom, its public statutes, its laws, and their distribution to the departments”. But the Assembly also acted because it was alarmed by popular initiatives in destroying physical vestiges of the Old Régime, including masses of written records. One month later, in October 1790, the Assembly created the Commission on Monuments to conserve artistic objects among nationalised property.

After 1789, a trickle of eminent and wealthy noble families went into exile to await what they assumed would be the imminent return of the Old Régime and good sense. Their departure posed a problem for the revolutionary government once the declaration of war in April 1792 turned this trickle into a flood and turned émigrés into traitors. If the landed property of émigrés was now to be sold off, what should happen to more personal possessions, such as their libraries? In May and June 1792 the Legislative Assembly had ordered the burning of huge mounds of noble genealogies found in former convents and monasteries. Some 300,000 books and manuscripts had been seized from émigrés; much else was simply destroyed. The royal library, dating back to the reign of Louis XI in the fifteenth century, was now to be their repository, and in September 1792 it became a public library, the Bibliothèque Nationale, the National Library.

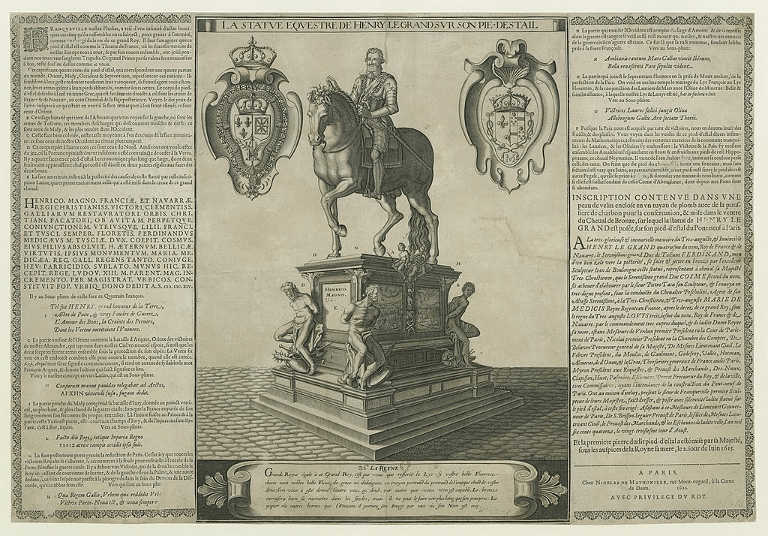

Statues of former kings were particularly problematic, especially following the overthrow of the monarchy on 10 August 1792 and the proclamation of a republic. On 11 August, the next day, the statues of Louis XIII, Louis XIV, and Louis XV in Paris were torn down. Henry IV‘s statue, erected in 1614 after his assassination in 1610, was torn down the following day. The rider and horse, Henri IV, were both destroyed, sparing only three pieces of the king, a part of the horse, and figures of four enchained slaves on the pedestal.

On the first anniversary of the overthrow of the monarchy, the nation’s republican unity was celebrated in Paris on 10 August 1793, at the Festival of the Unity and Indivisibility of the Republic. To mark this anniversary, symbols of ‘tyranny’ were burnt on the Place de la Révolution (today the Place de la Concorde), in the heart of Paris. A more formal ceremony was organised by the artist and Jacobin revolutionary Jacques-Louis David on the site of the demolished Bastille, where deputies and the oldest of the representatives of the departments filed past a new statue, the Fountain of Regeneration—this was a model of the Egyptian allegory of nature, Isis, from whose breasts spouted regenerative water to slake the representatives’ thirst for virtue.

The Republic’s grandeur was marked symbolically by the foundation of the public museum of the Louvre on the same day, a turning point in the history of museology. After Louis XIV had abandoned the Tuileries Palace for his new palace at Versailles in 1682, the Louvre had for a century housed the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, the Royal Academy, a maze of ateliers and workshops. In 1791 the National Assembly decreed it should become, instead, a museum for the nation’s masterpieces. It opened on 10 August 1793 with more than 500 paintings, mostly from royal collections or property confiscated from the Church. Its early administrators included prominent painters such as [Jean-Honoré] Fragonard and [François-André] Vincent. On 3 September an entranced student Edmond Géraud wrote home to his father in Bordeaux about the new museum, quote: “it is one of the thousand and one marvels of the Revolution. All of our works by Lebrun, Lesueur, Gérard Dow, Salvator Rosa, Raphaël, everything is there.”

Among the other items of heritage which were saved and which now reside in the Louvre were the statues of the four enchained slaves on the pedestal of Henri IV, along with the pieces of the king and horse.

Under the new republic the Jacobins and their supporters created a new symbolic universe to replace what they dismissed as defunct ornaments of oppression. For example, for the first time in history, common soldiers who fell in battle were honoured alongside generals and the Republic itself, a turning point in the history of war memorials. The scale and solidity of the memorials varied markedly: from a pyramid replacing a statue of Louis XV in Reims, and a stone pedestal in Auch erected with the names of the dead in large letters, to a wooden obelisk in Belleville on the northern edge of Paris, and a simple tree in the Pyrenean village of Villardebelle.

At the heart of divisions between the most militant of the Parisian revolutionaries, known as the sans-culottes, and the dominant Jacobins in the government was the extent to which the creation of a secular republican culture should purge France of physical traces of the Old Régime. There was often a tension between popular symbolic physical destruction of religious statuary, paintings, and other signs of the pre-revolutionary past, and Jacobin concern for the nation’s physical heritage. Drawing on images from classical antiquity of the sack of Rome by the Germanic tribe the Vandals in 455 AD [CE], the revolutionary Bishop of Blois, the Abbé Grégoire, coined the neologism ‘vandalism’.

In some regions of the country, however, even the physical existence of the Church was seen as suspect and retrograde. This became especially acute after April 1793, when a deteriorating military situation impelled the revolutionary government to impose draconian measures to place the country on a war footing and repress counter-revolution. The requisitioning of most church bells for armaments had already silenced large parts of the countryside. Deputies sent to the provinces to impose revolutionary decrees, such as Joseph Fouché at Nevers in Burgundy and Claude Javogues in the departments around Lyon, took the further initiative of closing churches. Where they were purged of alleged idolatry and turned into so-called ‘temples of reason’, there was large scale destruction of statuary, still visible around the entry of many provincial churches even today.

There were parts of the country where local people were predisposed to join in this ‘dechristianisation’, or even to initiate it; elsewhere, however, it was bitterly resented. Anti- clerical ceremonies had a carnival and cathartic atmosphere, often utilising the promenade des ânes (or the promenade of the donkeys), used in the Old Régime to censure violators of community norms of behaviour but, now, with someone dressed as a priest sitting backwards on a donkey. Such mockery was often accompanied by an iconoclastic purging of religious objects from the churches themselves.

An impulse to curtail the excesses of popular retribution was reflected in the Convention’s cultural policy towards libraries and heritage. In the spirit of the Abbé Grégoire, the Jacobin composer and poet Marie-Joseph Chénier vigorously opposed suggestions that offensive counter-revolutionary or royalist literature be destroyed: he insisted to the Convention that, in referring to the Enlightenment, quote: “we owe the French Revolution [to books] . . . There are very republican books that are dedicated to princes.”

This battle over the nation’s library heritage would occur even at the local level. In the east of the country, in the little town of Sarreguemines, the priest Nicolas-Antoine Baur abdicated his clerical functions in February 1794 and in May he became the town’s librarian, building an impressive collection from émigré property: the books from the Benedictine monastery of Saint-Avold alone filled twenty carts. Quote: “The establishment of libraries is for posterity one of the greatest benefits of the Convention”, stated a town councillor, “since it should efface the remains of ignorance and superstition and perpetuate the reign of Reason.”

While the Archives Nationales were created in 1790, it was a decree of 1794 that made it mandatory to centralise all the pre-French Revolution private and public archives seized by the revolutionaries. Then, in 1796, departmental archives were created in the regions of France, the basis of the national system today.

Battles over patrimony and monuments continued after the end of the Revolution. In Paris, the Vendôme column was started in 1806 at Napoleon’s direction and completed in 1810. Its veneer of 425 spiralling bronze plates depicting the Emperor’s military glories was made out of 180 cannon taken from the combined armies of Europe captured at Austerlitz. Napoleon was depicted as Roman soldier at the top.

After the Bourbon Restoration of the monarchy in 1815 the statue of Napoleon, although not the column itself, was pulled down. The statue was then melted down to provide the bronze for the recast equestrian statue of Henri IV on the Pont Neuf in 1818, an exact replica of the statue pulled down in 1792. The revolution was effaced.

The statue of Napoleon was re-erected on top of the column in 1864 by his nephew the Emperor Napoleon III. And, just seven years later, during the last and most radical of France’s nineteenth-century revolutions, the Paris Commune of 1871, the destruction of the entire Vendôme column was ordered.

A key role in the destruction was played by the artist Gustave Courbet, who was responsible for the formation of an artists’ federation, free of government regulation and patronage, to work, quote, for “cultural regeneration, the building of a communal heritage of beauty, the future development of art and the Universal Republic”. Incidentally, at the end of the commune, Courbet was later forced into exile and sentenced to repay the entire costs of reconstruction of the column. He died in 1877 before repaying anything, but the rebuilt column is there in Paris today.

In fact, it would be possible to write a history of France through these and other stories of battles over the symbolic use of public spaces. I have not even touched on the complex and fascinating history of street names.

One lesson from this history, however, is that this is contested history. As we have seen, the 1614 statue of Henri IV was toppled in 1792 but reconstructed in 1818 from a statue of Napoleon and is still there prominently today in the heart of Paris. And we need to remember that iconoclastic attacks on statues and other symbols can come from any direction. Even the statue of Voltaire – the philosopher who famously insisted that, quote: “discord is the great ill of mankind; and tolerance is the only remedy for it” – even the statue of Voltaire, in the Latin Quarter of Paris has recently been obscenely attacked.

The French anthropologist Daniel Fabre has produced a collection of essays titled Émotions patrimoniales, literally Patrimonial Emotions, although the term ‘émotion’ in French, when applied to collective attitudes, rather denotes ‘panics’. Fabre seeks to explain why public spaces and what they commemorate can generate such division and anger. But he also argues that we are still living through a sea-change across the past half-century, from what he calls the ’time of monuments’ to the ‘time of patrimony’. That is, argues Fabre, there has been, in many parts of the world, a shift from commemorating powerful men through statues to recognising patrimony in the sense of widely, although not universally, shared cultural markers such as places and events.

In Australia, too, the creation of heritage councils and registers is a measure of this new age of patrimony. We have seen, for examples, a limited democratisation of recognition through other memorials; for example on the Great Ocean Road, where the returned soldiers who constructed it from coastal cliffs were remembered close to the famous memorial arch in 2007. The nearby arch is at least the fourth in that place since 1936, although the earlier ones were destroyed by bushfires rather than iconoclasm.

There are many other ways to recognise ‘patrimony’. One of the explosive and violent battles of the era of the French Revolution was over slavery. The great Atlantic ports of Bordeaux, Nantes and La Rochelle had boomed across the eighteenth century because of their trade in colonial produce, produced by the slavery-based plantations of the French Caribbean. Slavery was abolished in 1794. A most powerful recognition and interrogation of the past through remembering a space is the slavery trail in Nantes, taking people pass the houses of eighteenth-century slave-traders and merchants to the dockside, where a harrowing display of objects from the slave trade is exhibited under the wooden wharves, whose groaning timbers evoke the reconstructed slave ship alongside.

In conclusion, our current debates and social movements need to be understood within this context of recognition of patrimony. The recent ‘Black Lives Matter’ protests in the United States, and in countries like ours with linked issues, have revivified concurrent debates about the appropriateness of statues of specific individuals. But anger has also been generated within the broader context of recognition of patrimony by the coincidence of these protests with the recent destruction of the Juuken Caves in the Pilbara. We know too that there are scores of other vulnerable sites in Western Australia, already approved under Section 18 of the Western Australian Aboriginal Heritage Act. Nor is the issue confined to WA, of course.

So, the other side of the coin from the current debates about the survivals from the ‘time of monuments’ is how well we are safeguarding irreplaceable heritage in the ‘time of patrimony’. At the time of the French Revolution the debate was very much about which statues and other physical vestiges of a hated past should be removed, who should make the decision, and what should be the fate of the statues themselves. Today it should also be about what should be remembered, in the sense of national patrimony and how we should do it.

Peter McPhee was appointed to a Personal Chair in History at the University of Melbourne in 1993. He has published widely on the history of modern France, most recently Robespierre: A Revolutionary Life (2012); and Liberty or Death: The French Revolution (2016). He was Chair of the History Department from 1996 to 1999. He was appointed to the position of Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Academic) in 2003 before becoming the University’s first Provost in 2007 to 2009, with responsibility for the design and implementation of the University’s new curriculum structures. He became a Member of the Order of Australia in 2012. He is currently the Chair of the History Council of Victoria, the state’s peak body for history.