Hagia Sophia Reigns Serene

Istanbul’s 1,500 year-old Hagia Sophia has a tumultuous history and its return to being a mosque is only the latest twist for a building that has long rolled with the times. SHAPS Principal Fellow (Honorary) Associate Professor Roger Scott, gives us a snapshot of its history in this article, republished from Pursuit.

If you were in Istanbul during an earthquake, and an earthquake hit the city as recently as last year, one of the safest buildings to be in would be the 1,500-year-old Hagia Sophia.

The great domed church-turned-mosque-turned-museum and, as of last week, now turned-mosque again, was built in such a hurry that the mud-baked bricks weren’t given time to dry properly, causing widespread hairline cracks. The happy but accidental outcome is that the building can rock without harm.

Which is just as well for a building with such a tumultuous past. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s decision to restore Hagia Sophia to a house of worship is only the latest twist in the building’s complex history.

The first Christian Roman emperor, Constantine, established Constantinople (now Istanbul) as an additional capital for the empire in 330, at the Greek city of Byzantium, renaming it modestly after himself as Constantinoupolis (Constantine’s city).

In creating an additional capital Constantine was only following in the footsteps of recent emperors. The large size of the empire meant that Rome was too far from the military frontier to be an effective base, leading to new capitals being established at Trier in Germany, Thessalonica in Greece, plus several elsewhere. Constantine’s oddity was to make his new capital a Christian city.

The Christian Byzantine Empire, was still just the same Roman Empire. Its inhabitants still called themselves ‘Romans’ (despite Greek being the dominant language), down to very end when Constantinople was finally conquered by the Ottomans in 1453. Thereafter, the Ottomans themselves still referred to their Greek subjects as ‘Rum’; that is, Romans.

Constantine built other churches but it was his son and successor Constantius, (Emperor 337–361), who first built in 360 a church beside the imperial palace known simply as ‘big church’ (megale ekklesia) or, with greater dignity, “the Great Church”. Only an early death prevented his successor, the pagan Julian, (Emperor 361–363), from turning it into a hay barn with horse stalls in the aisles.

The original structure was destroyed by fire in 404 during riots after John Chrysostom, the popular patriarch of Constantinople, was banished after insulting the empress. Upon being rebuilt the new church became known as both Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom) and “the Great Church”. This first Hagia Sophia was also gutted by fire during a huge riot in January 532 that lasted 10 days and destroyed much of the city.

Constantinople was a violent place frequently involving the supporters of rival chariot-racing teams (likened to football hooligans, although the teams also participated in imperial ceremonies).

But this riot, called the Nika Revolt, turned into an insurrection and was only suppressed when the army attacked spectators in the packed hippodrome that held about fifty thousand people. A contemporary states 30,000 were killed.

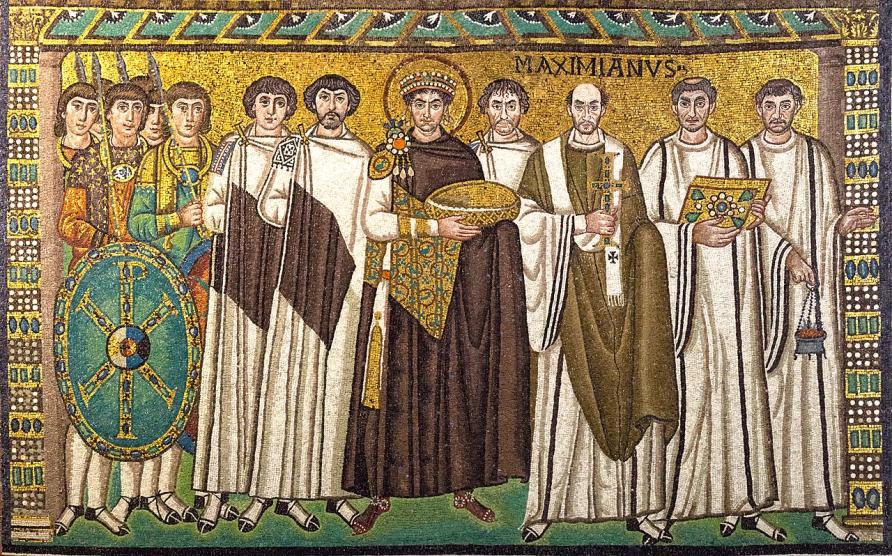

Unnerved by the riot, the emperor at the time Justinian had been ready to abdicate and flee until his charismatic wife, Theodora, famously told him “Purple makes the best winding sheet” (meaning it is best to die royal).

Fortified by Theodora’s determination the royal couple survived and Justinian went on to become one of Byzantium’s greatest emperors, responsible for the codification of Roman Law, Rome’s greatest gift to modern civilisation, and the recovery of the Western Roman Empire from the Vandals and Ostrogoths.

He started rebuilding Hagia Sophia almost immediately. Within just five weeks of the riot the site had been cleared, building materials acquired, and, most remarkably, a revolutionary design adopted that would amaze the world. The new building was completed by December 538 in five years, 11 months and 10 days precisely, as stated in several Byzantine chronicles.

In terms of its size, that is about as fast as modern buildings take to construct, but the speed is even more remarkable given the short time apparently taken to produce such an original design.

The architects, Anthemius and Isidore, were also engineers and mathematicians. Among their innovations was the huge dome that, curving gently, appeared just to float in the sky. Unfortunately it was too daring and it collapsed in 558. Isidore’s nephew, also Isidore, restored it more safely 30 feet higher, and the church was rededicated on Christmas Eve 562.

Shortly before Justinian became emperor, the noble woman and descendant of Emperors Anicia Juliana had just built the biggest church in Constantinople, the Hagios Polyeuktos, and in an inscription had proudly described it as being comparable to Solomon’s temple and herself as descended from royalty. Its ruins, identified by Anicia’s inscription, reveal its lavish decoration.

Justinian, who came from a humble background, may have felt he had a point to prove in church building.

On first entering his newly restored Hagia Sophia he reportedly shouted “Solomon, I have outdone thee!” He perhaps really meant he’d outdone Anicia Juliana.

The new church had a staff of 485 and played an important role not just in religious life but also in imperial ceremony.

The emperor, who was officially chosen by God, would enter the hippodrome direct from the palace at an upper level. Each chariot race celebrated the state’s victories over its enemies, granted by God in return for orthodoxy, and celebrated in nearby Hagia Sophia with numerous religious processions between palace, church and hippodrome and other parts of the city.

A 9th-century Book of Ceremonies details the ceremonies over several hundred pages. A hundred years on from its construction, the number of staff at Hagia Sophia had grown to 688.

Hagia Sophia’s original Justinianic decoration was largely non-figural, surviving mainly in the vestibule. The gorgeous figural mosaics were only introduced across the 9th to 13th centuries, and most were only revealed after the church became a museum in 1934.

There were also later repairs, including the addition of massive buttresses added in 1317. Further work was undertaken by the Ottomans, the most important by the Swiss Fossati brothers in 1847–1849.

Hagia Sophia was damaged in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade when western Christian crusaders looted orthodox Christian Constantinople.

In marked contrast when Constantinople’s Ottoman conqueror Sultan Mehmed II entered Hagia Sophia on 29 May 1453, he immediately ended the looting, and arranged for the Christians, who had flocked to Hagia Sophia expecting deliverance by an angel, to depart in peace, before proclaiming it a mosque.

However, despite all the repairs, the basic building remains that of 532, a remarkable achievement for the original architects and builders.

Hagia Sophia ceased being a mosque in 1922 and became a museum in 1934 after being the main religious building for two influential empires, the Byzantine and Ottoman. Studying both empires helps us to understand major modern trouble spots in their former territories, notably the Balkans and the Middle East.

Through it all Hagia Sophia has withstood the storms of politics and nature – including earthquakes. We are lucky to have her.

Feature image: Hagia Sophia, 2014. Photographer: Adli Wahid via Unsplash