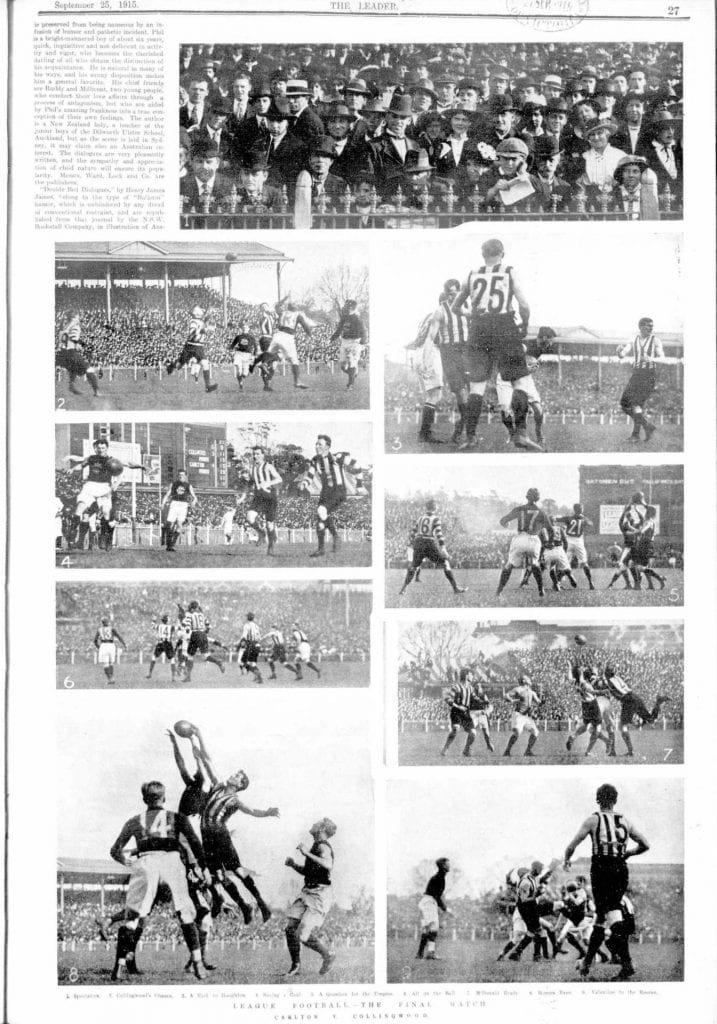

Sport, Community and Everyday Life: World War One and COVID-19 Compared

For many Australians, the economic pain brought by the COVID-19 crisis has been compounded by the disruption caused to sporting activities. For football-loving Melburnians, the very rhythm of the week was rendered unrecognisable after the temporary suspension of the 2020 AFL season in March. The closing down of sports at the local community level has also been a difficult aspect of the lockdown, leaving many feeling bereft and socially disconnected.

There’s often a tendency to think of the current crisis as unprecedented; however, as historian of sport Dr Xavier Fowler shows in this article, the feelings of sadness and grief that many have experienced in connection with the loss of sport this year finds parallels in the human responses to the dramatic decline that Australian sport underwent during World War One.

Sport has long held a prominent and seemingly unassailable position in the Australian national landscape. Sport occupies an especially important place in Australian culture and everyday life, and this has made COVID-19’s devastation of all aspects of sporting activities across the country all the more shocking.

The impact of the pandemic on the country’s sporting industry was swift and brutal. The enforcement of social-distancing practices brought the suspension of almost all sporting activity in March. As a result, gate receipts and broadcast revenue evaporated, and this placed the major sports bodies in an altogether catastrophic financial position. The Australian Football League (AFL) faced the prospect of a $500 million loss without the completion of a full season. The National Rugby League (NRL) confronted the prospect of total collapse. The subsequent push to cut costs left players, administrators, and staff facing significant pay reductions or termination.

Great efforts have been made to continue with the AFL season and other sports in an attempt to lessen the financial hardships of those connected with the industry. This has included the removal of players from their homes and quarantining from their families, and, last month, moving the entire game interstate as Victoria faced a second lockdown. Yet even such noble sacrifices have provoked criticism. Is sport an appropriate activity in a time of national crisis? The Age columnist Greg Baum was one of those who argued emphatically that now was not the time to be playing football. Baum was highly critical of the AFL’s survivalist instincts; the interests of the sport, he asserted, must take a back seat to safeguarding the health of the wider community:

The subtext of the AFL’s decision to forge ahead is that footy is too important not to be played … But is it? Can it ever be? … The argument that footy can act as a distraction does not hold water. What we need now is concentration, not diversion. This is not the time for bread and circuses.

But sport is not just a matter of bread and circuses, and not just a matter for elite spectator codes. Indeed, it is not just the upper echelons of Australia’s sporting community that have been hit by the effects of COVID-19. The pandemic has also devastated local and community sports at all levels, including junior and socially organised games. The demise of local sport has deprived many of their sense of purpose, place and community – all this, moreover, at a time when other aspects of the crisis have already taken their toll on mental health.

The situation facing the sporting community in 2020 is in many ways unprecedented. But it also recalls in many ways an earlier historical case, when Australian sport experienced a similar decline: the case of World War One. Many political leaders have been quick to draw parallels between the current health crisis and the challenges of wartime. Such crude comparisons must be treated with caution, especially given their potential to be used for manner of exploitative and manipulative ends.

And, of course, there are fundamental differences between war and pandemics as phenomena. At the same time, however, these two categories of disasters do have some things in common. In both cases, we find a major displacement of the communal and private structures governing everyday life. In this connection, it’s worth taking a look back at the history of Australia sport during World War One. What we find is that both crises produced strikingly familiar human responses.

Contrary to the popular myth, World War One was as much a nation-breaking as it was a nation-making event for Australia. As young men were massacred abroad in their thousands, the intense pressure the war effort placed on civic life at home aggravated dormant ideological, class and sectarian hostilities. Sport did not escape this turmoil; and the divisions wrought by the war were reflected on the playing field too.

The war prompted fierce debates over issues around sport. Patriots and government officials regularly complained that spectator sport distracted young men from enlisting while simultaneously consuming public finances better spent on the war effort. These criticisms usually came from the Protestant middle class, who generally maintained stronger links with Britain and, therefore, had higher expectations of civic loyalty to Empire.

Middle-class sporting administrators moved to cancel their games in response to these grumblings, so that players and supporters could focus their attention on national interests. In contrast, the Irish-Catholic and working classes were more likely to defend the continuation of their sports as a necessary distraction for a population overburdened by the pressures of total war. The clash over sport shadowed wider wartime debates over what constituted an acceptable level of commitment to the war effort. Disputes over industrial working conditions, control of food prices and, of course, conscription raged during these years, pitting middle- and working- class Australians against one another.

Reading the newspapers of the time, we find evidence of the strong emotions aroused by the debate over sport. Sydney resident Gladys Fitzpatrick wrote in 1916 with particular animosity to the Sun newspaper about the selfishness of ‘Young Australia’. Fitzpatrick reserved special mention for eligible young men, who had forsaken their inviolable duty to Empire in favour of attending boxing and football matches with “poisonous weed protruding from their lips.”

Over time, the clashes over sport moved into the streets and the stadiums. In 1917, the enmity between the two factions became so acute that there were reports of violent encounters between military recruiting agents and sports fans. Sergeant Kilpatrick, who visited a Victorian Football League (VFL) match in May, reported that he was “pushed” and “jostled” by the crowd, who cried out that he had no right to “spoil their sport” with talk of war. Sport – an activity designed to bring people together – was now tearing Australians apart.

The mounting pressure brought about by middle-class patriots eventually convinced government officials to restrict those sports that had refused to discontinue, including boxing and horseracing. These interventions only prompted further anger from those who derived their livelihoods and leisure from sport. A letter from former racing employee and AIF veteran Leo Powell to Victorian Chief Secretary John Bowser in 1919 expressed the feelings of many disenfranchised Australians:

When there was a German enemy to be beaten and a danger of rich men losing their wealth, if not their lives, we were exhorted to join up and fight to keep Australia free … When I returned it was my first desire to resume my occupation as a trainer of racing ponies. The Government I found, had lessened my opportunity to earn a living by 75% and I have to struggle on as best I can at the only business of which I have any knowledge, or swell the number of workless soldiers… Let the Government give those who risked everything in freedom’s fight a fair chance to return to the conditions that prevailed before the war and there will be less discontent, which is the seed of Bolshevism … Must we have to fight for justice and the right of fellows in our occupation in our own country?

Self-imposed and forcible restrictions of sport during the war years combined to precipitate a sharp financial decline among Australia’s major sporting organisations. By the final year of the war, gross revenue for the New South Wales Rugby League had fallen to one-third of its pre-war income. In other cases, the fall was even more dramatic: income for the Western Australian Football League fell to one-sixth; for the VFL, to one-ninth. For these non-profit organisations, the downturn posed a serious threat to the survival of their codes.

The situation was even more dire for Stadiums Limited, a publicly traded boxing corporation responsible to thousands of shareholders and employees. The company’s Board of Directors watched on in horror as its revenues plummeted from 1916 onward. Attendances fell by 75 per cent, as bouts that once drew £200 now brought just £30. The 1917/18 financial year culminated in a disastrous loss of £8,035 (roughly $780,000 today). Because of this, administrators were compelled to close operations in Sydney and Brisbane and terminate all staff.

But the losses involved were not just financial. Just as it does today, sport in early twentieth-century Australia enhanced mental well-being by developing social relationships. Participants and spectators involved in organised sports had a sense of belonging to a broader community, with a special place or role within that community. As a result, for many, the absence of sport, particularly at the local level, gave rise to feelings of isolation, loneliness and depression.

The words of Australasian cricket correspondent Tom Horan, writing in 1916, speak to this sense of void:

Where now is the throng of eager and excited lookers-on, the tumult and the joy, when the light of victory was in your eyes, as the captain roused the thousands by his stirring speech in front of the pavilion at the close of play? … Those stirring days of club cricket will probably never come again.

For Horan, this was unfortunately true. His health had been in decline and he would succumb to oedema only a few months after penning these words.

For Horan and countless others like him, the call for a total public commitment to the national war cause had meant being deprived of the place in the world that they had found in sport. Horan’s wistful nostalgia also reflected the changes brought not just by the departure of the community’s young men, but by social disharmony at home.

The past offers no blueprint for the future. But it might provide direction to help navigate the perils that previous generations have encountered when confronted with seismic disruptions to their everyday life. It can also bring a sense of comfort to know that others too have shared similar experiences. Indeed, the recent reflections of ABC sports commentator Richard Hinds over the gloomy state of local sport in Australia share a melancholic kinship with Tom Horan’s yearnings for happier days 104 years earlier. Many in wartime Australia would surely agree with Hinds’ observation, that ultimately, “It is the simple absence of the gathering of weekend tribes that will be felt most.”

Dr Xavier Fowler completed his PhD at the University of Melbourne in 2018, on the history of social conflict in Australian sport during World War One. He has published several articles based on his research, including, most recently, ‘“Bitter Enemies of the Sporting Fraternity”: The War Precautions Act and Restriction of Horse-Racing in Australia during World War One’, International Journal of the History of Sport 36:12 (2019). Xavier currently teaches twentieth-century history at Deakin University.