Astronomy in World History

One of the most popular subjects in the History and Philosophy of Science program is the second-year summer intensive, Astronomy in World History (HPSC20015). Conducted over ten days, this subject explores the history of astronomy across a variety of cultures including the Babylonian, Ancient Greek, Chinese, Indian and Arabic civilisations. As well as learning through lectures and readings, students also engage in hands-on practice, using their own handmade astronomical instruments as well as professional replicas to observe stars and other objects in the sky. In this interview Samara Greenwood, a recent tutor in the subject, spoke with Dr Gerhard Wiesenfeldt about what inspired him to create such a novel and engaging format for his subject.

Could you briefly describe what the subject Astronomy in World History is about?

In the subject, we look at the development of astronomical thought in ten different civilisations.

While there is a focus on the Eurasian continents and early modern Europe in particular, we also include Mesoamerican and Australian Indigenous astronomy. We also discuss how astronomical knowledge was transferred between different civilisations and what happened to that knowledge in the process.

One aspect that is very important to me is to show that local traditions didn’t just stop when modern ‘Western’ astronomy came to other parts of the world. For example, in India or Mexico we find an integration of traditional and modern practices.

Could you describe some of the unique aspects of the subject?

The subject combines traditional learning forms – such as lectures and text-based tutorials – with practical activities. We go out in the evening to observe the night sky using instruments the students have made themselves. Students also work with professionally made replica instruments such as astrolabes and armillary spheres.

One third of the classes is devoted to practical matters – including astronomical observations, calculations of planetary motions and the production of birth charts.

How did you first come to teach the subject and how has it evolved over time?

When I arrived at Melbourne in 2007, I took over the subject from my predecessor Keith Hutchison. At that time, it was called ‘History of Astronomy’ and focused on the development within the Western narrative. It aimed to give students an introductory overview to the history of science.

Given we were introducing a new first-year subject, From Plato to Einstein (HPSC10001), which did just that, I needed to change the scope of the subject and decided to focus on the history of astronomy in different civilisations.

In teaching the subject I found many students struggled to understand key concepts, as they had little prior knowledge about the civilisations we were discussing or about astronomy. So, in 2012 I decided to move the subject to a summer intensive so I could introduce astronomical observations to help students better understand how astronomy used to be practised.

Given this has been very successful, we’ve continuously expanded the practical components. Thanks to a Learning and Teaching grant in 2016 we have been able to move the lectures online, freeing up time in the classroom for practicals.

The subject invokes an unusual level of enthusiasm from students, why do you think they find it so engaging?

There are probably a couple of different factors.

Students tend to find the subject material interesting but for many participants it is also their first serious engagement with the night sky. With the hands-on approach in the subject, the students experience a very direct way of learning that is linked to profound theoretical questions about the status of scientific knowledge. Also, the structure of a summer intensive suits many students – it is only running for a short time but requires a full-time commitment over that period.

Of course, it helps that many activities take place outside during good weather.

The subject also attracts students from a diverse array of disciplines; for example, in my workshops I had students from science, architecture, economics and arts. What do you think the subject offers students from different disciplinary backgrounds?

There are so many different aspects in the subject that for almost every student there will be something they are familiar with and gives them some strength to build on.

On the other hand, that also means students will encounter things they have never had contact with. This allows them to expand their thinking in new ways. The subject also allows for a gentle introduction into ways of thinking some students might feel a bit threatened by. For example, some arts students find maths-based scientific content challenging, while many science and commerce students have never before considered the historical contexts in which knowledge develops.

What do you enjoy about teaching the subject? Do you have any particularly memorable experiences?

Teaching the subject is always a bit of an adventure, there are always a lot of unknown circumstances that need to be taken into account, not the least the Melbourne weather.

Yet almost everybody in the subject is happy to improvise at short notice, so it is fun to teach and also very rewarding to see the students engage with the material. The observation nights especially stay in your memory.

At one such occasion, we had just been starting the observations, when a very bright meteor lit up the sky. While this was spectacular for everybody, some students were astonished as they had never seen a shooting star before. I realised that people growing up in places like Singapore and Hong Kong would hardly have had the chance to get used to the night sky. I felt somewhat bad when I had to tell them that shooting stars were not that special but a rather normal occurrence.

I found many students showed high levels of creativity in their assignments. What are some of your favourite examples of student projects?

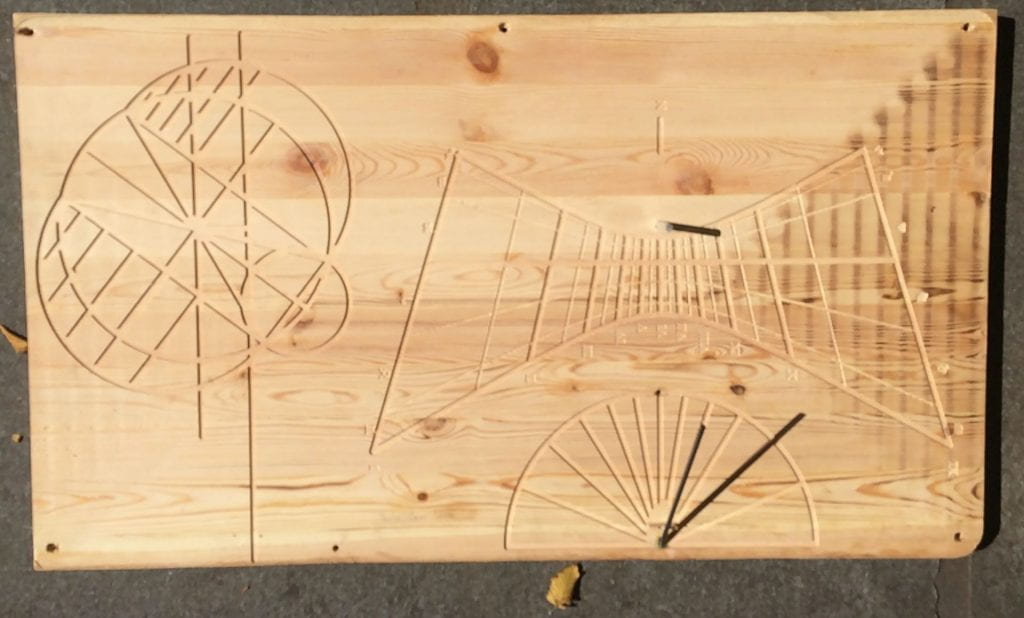

There are so many to choose from! Of course, there are students who go to a lot of effort when they choose an assignment option that allows them to construct a sundial according to a prescription from the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius. While this can be done on paper or cardboard, some students have produced wooden models, including a very Australian model made out of plywood that probably could double up as a surfboard.

For the report on their night time observations, we had one student modifying their parents’ garage to calibrate their self-made instruments, while others have measured their thumb and arm-lengths to gauge the accuracy of the ‘rule of thumb’ (the width of your thumb held at arm’s length is approximately equal to 2 degrees elevation – this can be used to estimate the angular elevation of a star above the horizon).

Where do you see the subject going in the future?

Hopefully continuing for some time. One thing I want to work on is to include more non-European material into the practical side of the subject. There are some obstacles in terms of availability of materials that I hope to overcome in the near future. Otherwise, colleagues overseas have asked me to write a textbook on the subject, yet I’m not sure whether I want to go to that level any time soon.

More on Gerhard’s work with replica astronomical instruments can be found in the Forum article Researching History on the High Seas.

Feature Image: Students using replica astronomical instruments, the astrolabe and cross-staff, Astronomy in World History (HPSC20015), 2019. Photograph: University of Melbourne