What was it Like to be a Child in the Roman Empire?

As the researcher for a new children’s novel set in Ancient Roman times, archaeologist and SHAPS Honorary Tamara Lewit found herself hunting for answers to questions she’d never considered. She tells us about Roman childhood in this new article republished from Pursuit.

What would a school day be like in 313 CE? What games would children play? What would a ten-year old girl wear? What medicine would a child be given for a cough?

For 40 years, I had researched the archaeology of late antiquity – the later Roman Empire from the third century onwards, to the transition to the early middle ages and Byzantine eras.

But I was being asked a completely different set of questions – and I had no idea yet of the answers.

My eldest sister, historical novelist Anna Ciddor, had asked me to help her write a children’s novel to be set in fourth-century southern Gaul, a region of the Roman Empire, which is now part of France.

“We should write a book together,” she had texted me one day. Was she serious?! It would be like going back to our childhood, when Anna created characters and drew their portraits, while my middle sister and I looked on in awe and carefully coloured them in.

“Yes”, I had replied hastily, before she changed her mind. So began a quest to make the late antique past accessible and alive to children.

Although there has been valuable recent scholarship on ancient childhood, I was on a mission to do something different: to engage modern children with their peers in the past.

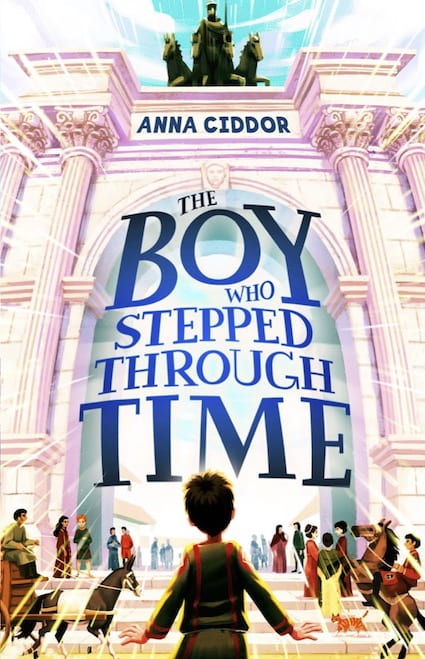

Nearly three years later, The Boy Who Stepped Through Time, in which a modern eleven-year-old boy accidentally finds himself in fourth century Gaul, has just been released.

Having spent my research life studying the Roman countryside, I demanded that Anna set the novel at a late antique villa and, at our first planning session, I arrived with an armful of books.

But my confidence was soon shattered.

As a creative writer trying to envisage history from a child’s viewpoint, Anna asked questions that had never entered my head about how ancient children had actually used and experienced the objects and places I had researched.

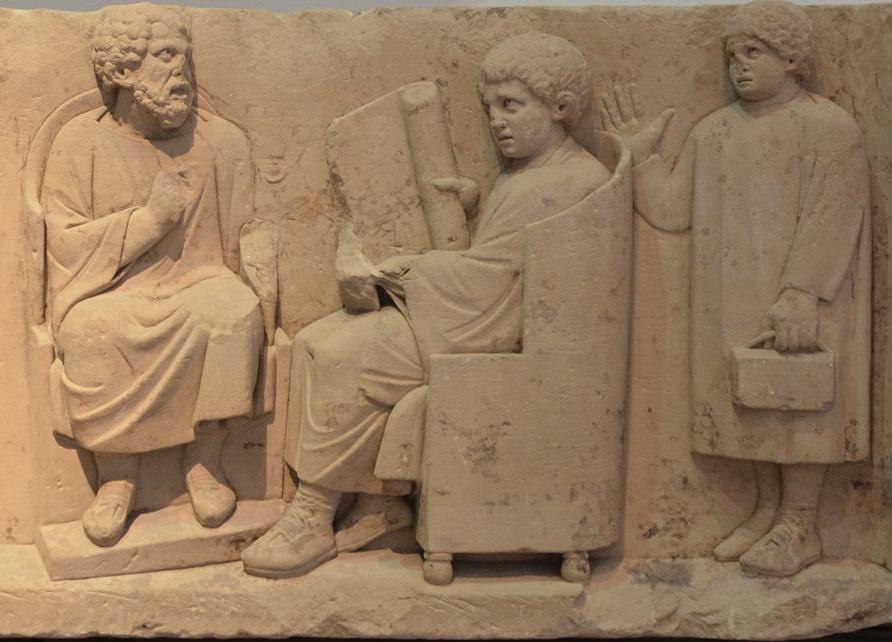

I had to reinvent myself as a researcher, tunnelling into sources I had never before investigated. The search led me to a Roman school text (designed to teach Greek) that describes a day in the life of a young boy, a medical handbook for travellers wary of trusting foreign doctors, as well as mosaics showing images of children at work and play.

Initially, Anna planned the novel as the story of a girl in Roman Gaul. But when she trialled this early draft in primary schools, she was dismayed by how unfamiliar students were with the ancient past, and how few words and concepts they understood

We had to find a better way to help our child readers see the scenes and empathise with the ancient characters.

The solution was to rewrite the book as a time-slip novel, creating the character of a modern boy, Perry, who would travel back in time to meet our ancient heroine, Valentia. This made it possible to describe the past as our child readers would see it.

But what would Perry experience in his adventures, and how would he meet the Roman girl we had imagined?

The spark came when I told Anna that grieving Roman parents wrote the exact number of years, months and days their dead children had lived on their graves.

“Don’t mention that museum,” groaned Melissa. “I still can’t believe you and Mum spent two hours looking at dead people.”

“It wasn’t dead people. It was ancient stone coffins. From Roman times,” protested Perry.

“Same thing.”

“Well, they were interesting. I found one of a girl who died when she was exactly my age: eleven years, two months and one day old.”

In the ruins of an ancient villa, Perry slips back in time and forges friendships across the gulf between himself and Valentia, and a mischievous Roman slave boy, Carotus.

Having once heard the French historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie describe the historian as one who connects the living with the dead, I see these friendships as symbolising the link I hope to make between the real children of the Roman past and the modern children of today.

In my search for accurate details, I became a tomb-robber, stealing jewellery and amulets found in child burials for our Roman girl character.

Meals were based on the archaeological remains of ancient food, like carbonised grains, and the recipes collected in late antiquity under the name of Apicius.

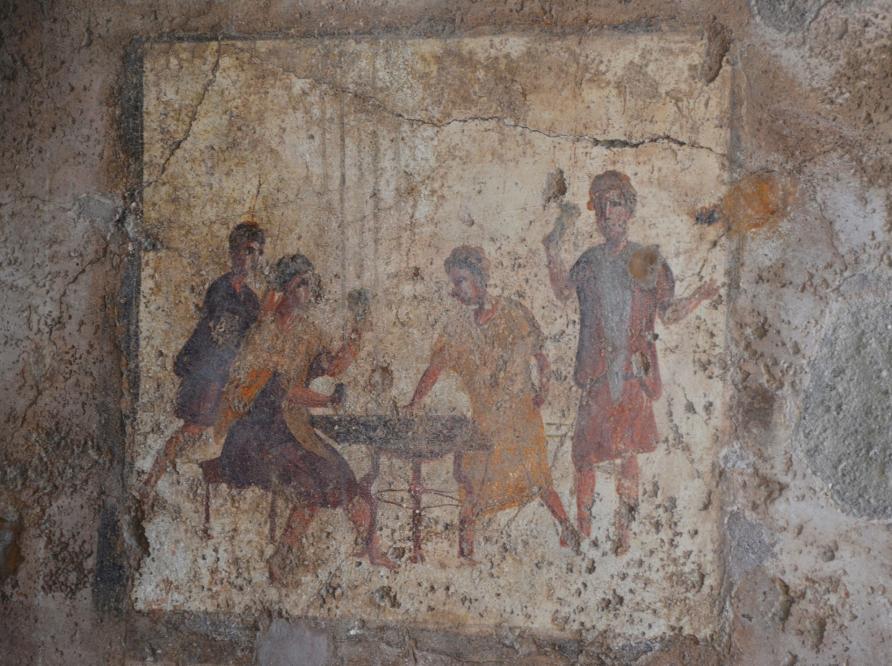

The slaves got their names from the stamps which Gaulish potters put on their work. A wall painting of a dice game with speech captions from Pompeii became the inspiration for a quarrel in an inn.

I pored over all 12 books of Roman agricultural writer Columella for details like the suitable colour and name for a guard dog at the villa (Lupa, or ‘Wolf’, is black – to frighten thieves).

A set of third-century moral sayings for children proved to be a goldmine for quotes repeated by the doddery old tutor in our novel, Balbus.

I drew heavily on my own archaeological research into wine and oil making technology – an ancient artisan’s error when carving the holes in an oil press stone even became a key element of the plot.

But to understand more of the lived experience of traditional farming I read nineteenth- and twentieth-century-memoirs, and Anna and I even went grape treading together at a Melbourne winery.

It was magical to see the rubble and dust of ancient remains that I had studied for so many years brought vividly to life through the lens of Anna’s imagination.

This project has also prompted a new direction in my research.

My book chapter Young Children in the Roman Farming Economy (Western Mediterranean): “… Not Only Boys but Even Girls Tend Flocks”, which incorporates nineteenth- to twenty-first-century ethnographic material and the visual record of mosaics alongside Roman agricultural writings, will soon be published by Palgrave Macmillan in Reframing the Roman Economy: New Perspectives on Habitual Economic Practices.

As for some of the questions Anna posed – what would a school day be like in fourth-century Gaul?

The students – mostly boys, but probably some girls – would read aloud poetry, which was quite hard as Romans wrote with no spaces between the words. They would also chant times tables and learn to read Greek.

Children played with knucklebones, nuts, glass marbles, wooden tops and even yo-yos. A ten-year old girl would wear amulets such as a crescent moon, a wolf’s tooth, or a bangle with a bell to scare away ghosts and evil spirits with its sound.

And a remedy for a cough? Try horse saliva drunk with hot water, or pigeon dung gargled with raisin wine, or even ground millipedes mixed in vinegar and honey.

To extend the impact of the novel, we have constructed an extensive website based on my research, and teaching activities for Year 4–7 English and History teachers.

The Boy Who Stepped Through Time was released on 1 June, and will be launched on 20 June via Zoom.

I warmly thank the historians and archaeologists who generously advised me, particularly Jacques Bérato, Paul Burton, Alexandra Chavarría, Ash Green, Tim Parkin, Yolanda Peña Cervantes, Eric Poehler, Richard Reece, and my son Lucas, who studied Latin at the University of Melbourne and helped with the translation of many primary texts.

Feature image: Illustration by Anna Ciddor of Villa Rubia as it appears in her novel The Boy Who Stepped Through Time.