Donna Merwick Dening (1932–2021)

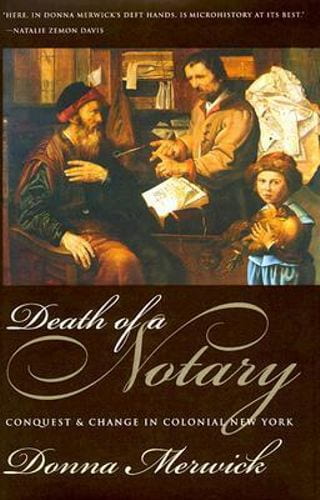

On 23 August SHAPS received the sad news that Donna Merwick Dening had passed away overnight. Donna was an Associate Professor in the History Department from 1969 to 1995 and taught American History. She was teacher, mentor and colleague to many and we mourn the passing of a great historian. Donna was proud of the books she wrote and they will endure as her legacy. She taught us about dealing with cultural difference, writing as a craft, the necessary depth of research, and being honest with the reader. Donna’s work, Death of a Notary, is still read by students in the History capstone subject, Making History (HIST30064). In this piece, written for Forum, her colleague and friend, Professor Charles (Chips) Sowerwine honours Donna’s life and career. – Andy May, Head of History.

Donna Merwick Dening: A Personal Reminiscence

Chicago, 14 February 1932 – Melbourne, 22 August 2021

Associate Professor (American History), The University of Melbourne, 1968–1995 [1]

Nothing in Donna Merwick’s early life presaged that she would come to Melbourne and make her career there. That she did was the result of extraordinary coincidences or, as some might say, Acts of God. Donna was born in Chicago, one of three daughters of James and Lydia Merwick. The family was comfortable (James was a veterinarian) and solidly Catholic. Donna attended a Catholic high school and then a Catholic women’s college, Mundelein College, founded and run by the Order of the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary.[2] In 1953, she graduated from Mundelein and joined the Order. Since she had studied History, the Order assigned her to teach History and English at one of its Chicago High Schools. During the summers, she undertook an MA at DePaul University, Chicago. She could assume that the rest of her life would unfold in Chicago, within the Order.

“But one day”, Donna later recalled, “the Superior General (as she was called in our congregation) came to our school, and she said that she wanted to send me to the University of Wisconsin for a PhD. So, it wasn’t my choice, it was not my ambition, it was just: off you go.”[3] In 1961, the year before her MA was awarded, she began a PhD in American History at the University of Wisconsin. This decision, made for her and accepted in obedience, set Donna on the path to independence.

It also set her on the path to Melbourne via Wisconsin, whose History Department had surprising links to Melbourne’s. I must introduce myself into the story now because Donna and I shared a Wisconsin connection and it played a major role both in our lives and in our friendship. I came to study History at Wisconsin the year after Donna left and my coming to Melbourne, like Donna’s, was a direct result of the Melbourne-Wisconsin connection, which involved three key Melbourne personalities: Kathleen Fitzpatrick, Max Crawford and Norman Harper.

In the US during 1954 as a visiting British Commonwealth Professor courtesy of the Carnegie Endowment, Kathleen Fitzpatrick was “enchanted” by the University of Wisconsin History Department, “the ‘best’ she had encountered”. It was, she noted, similar to Melbourne in its “strong sense of existence”. She was particularly impressed by Merle Curti, the Frederick Jackson Turner Professor and Head of History at Wisconsin: an “outstanding personality”, as she put it in a letter to her close friend Max Crawford, the legendary Head of the Melbourne History Department, another outstanding personality.[4]

Encouraged by Fitzpatrick and, as Donna suggests in her insightful piece on the Crawford-Curti correspondence, by his own admiration for Curti’s The Growth of American Thought, which won the 1943 Pulitzer Prize,[5] Crawford planned a semester at Wisconsin as Visiting British Commonwealth Professor. Originally scheduled for 1957, Crawford cancelled the visit because of his wife’s illness but Curti renewed the invitation, inviting him to deliver the prestigious Knaplund Lectures in addition to a lecture course on Australian History. In 1958–1959, Crawford spent five months at Wisconsin. Curti and Crawford became close friends and corresponded until Crawford’s death in 1991. Curti visited Melbourne in 1964, the year that Donna completed her postgraduate coursework at Wisconsin.[6]

Melbourne’s Norman Harper, who had taught the first American history subject offered at an Australian university (in 1948), was led to Wisconsin by his longstanding interest in Frederick Jackson Turner’s extraordinarily influential ‘Frontier Thesis’, which he formulated at Wisconsin. During his later career at Harvard, Turner supervised Curti’s PhD. Harper’s interest in Turner inspired a brilliant undergraduate at Melbourne to pursue a doctorate not at Oxford or Cambridge but at Wisconsin. Paul Bourke arrived at Wisconsin in 1964, like Donna, to study with the same historians, Merle Curti and a newcomer, William R Taylor, whose 1961 Cavalier and Yankee: The Old South and American National Character was receiving acclaim. In this book, Taylor extended Curti’s approach to culture as shaped by social constraints, showing how the North and the South’s perception of the other’s culture shaped their evolution as they approached the Civil War. When I arrived at Wisconsin in 1965, Taylor was the hottest thing going in intellectual history.

Meeting as fellow newcomers in Curti and Taylor’s seminar, Donna and Paul struck up an abiding friendship. Donna became a regular babysitter for Paul and Helen. Paul and Donna both completed their coursework in 1964. Paul returned to the University of Melbourne to take up an appointment as Lecturer and Donna went to Boston to undertake research for her PhD thesis.

That thesis was to be called ‘Changing Thought Patterns of Three Generations of Catholic Clergymen of the Boston Archdiocese from 1850 to 1910’. If the topic kept Donna within a Catholic framework, the question of evolving mentalities shaped by social developments both reflected Curti’s interests and foreshadowed the ethnographic approach she would pioneer in subsequent work. From late 1964, Donna lived in a Church Study House overlooking the Boston Public Gardens. She kept in close touch with Curti and Taylor, sending them drafts, and occasionally traveling back to Wisconsin to consult them in person.

Donna shared with many other Catholics the unfolding hope that the Second Vatican Council (Vatican II), opened by Pope John XXIII in October 1962, would offer a path to a modern, progressive and inclusive Catholicism. In November 1964, the Study House began regular meetings of priests and other religious to discuss reform and renewal of the Church in the light of Vatican II. At that first meeting, “a young priest said that he was from Australia and I said, oh, I have good Australian friends at Wisconsin, Paul Bourke and Helen. And he said: Paul Bourke is one of my best friends.”[7]

That young priest was Greg Dening, a Jesuit from Melbourne who was undertaking a PhD in Anthropology at Harvard. Greg was another Melbourne History graduate who, like Paul Bourke and so many others, would return to Melbourne after completing a PhD elsewhere. Greg and Donna always said that they hit it off immediately. Their conversation was supercharged as they discovered their shared engagement on civil rights and Vietnam as well as Vatican II. Let’s give Donna the last word:

So anyway all of that went on, with the Vatican Council [Vatican II] and civil rights movement and Vietnam – exactly the sixties kind of stuff. I also began to have thoughts about staying in the religious community as a nun, and Greg and I became closer friends, although he was a priest. We had to be very careful. I think we knew we loved each other but that we would never be together.[8]

They could, however, be together as ‘closer friends’, at least while they were both in Boston working on their PhD theses. But Donna worked conscientiously, as always, and in 1966, she submitted her PhD (it was awarded in 1967), left Boston and returned to Mundelein College to teach History. Just as when the Superior General sent her to Wisconsin, she could assume that the rest of her life would unfold in Chicago, within the Order.

Returning to forge a career at one’s undergraduate institution, as Paul and Donna did, was still common in academic life. The Melbourne Department of History was largely staffed with Victorians who had earned their undergraduate degrees at Melbourne, often going abroad (usually to Oxford or Cambridge) to earn a higher degree and then to return in triumph. Before Donna’s appointment, transplants from North America were almost unimaginable; even interstate transplants were rare, though Crawford came from Sydney when appointed Professor in 1936.

By the 1960s, to be sure, this was beginning to change. Harper, of course, had long looked to the US, but now others did so too. The emergence on the world of American higher education, aided by the Carnegie and Fulbright programs, was reorienting Australian academic life toward North America. Paul Bourke and Greg Dening were among 15 Melbourne History graduates who completed Fulbright funded PhDs in North America in the 1960s.[9] In 1968, John Poynter received a Fulbright grant to tour US graduate schools in history. He was now Ernest Scott Professor, alternating with Crawford as Head of Department. They were, as he later wrote, “casting the recruiting net wide, seeking in particular staff with postgraduate experience in North America”, aiming to move beyond the Melbourne-Oxbridge nexus.[10] But as Donna began to settle into life at Mundelein, she could never have imagined that Melbourne would soon make her its first North American appointment. That it did was the result of another series of coincidences in the lives of her two closest friends.

Greg Dening took up a one-year appointment at the University of Hawaii (1967–1968), which enabled him to continue research on his PhD. He returned to Australia still committed to The Society of Jesus and completed his second thirty-day ‘Long Retreat’ (twenty years after the first), devoted to practicing the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius Loyola.[11] The Order then posted him for what turned out to be a very brief appointment as Chaplain at the University of Queensland. In July 1968, Pope Paul VI issued Humanae Vitae (the encyclical prohibiting birth control). The Australian bishops decreed, in addition, that all those exercising priestly functions must preach the rationality of the encyclical. Greg could not accept that condition and he was thus unable to perform his duties. Despite the Jesuits’ support, he had to leave the Society.[12] Almost immediately, he was appointed Senior Lecturer in History and Sociology at La Trobe University, taking up his appointment in 1969. Greg was no longer a priest.

Paul Bourke took up a lectureship at Melbourne in 1965. Like Donna, he would have expected to make his career at his undergraduate institution. But the creation of new universities offered unprecedented opportunities for academic staff. In 1969, Paul “was unexpectedly appointed Foundation Professor of American Studies at Flinders University [Adelaide], leap-frogging all other ranks”, as John Poynter puts it.[13] Crawford, Poynter and, especially, Harper had counted on Bourke. Now they had to move quickly to replace him. Paul wrote to Donna, presumably with Crawford’s blessing, “asking whether I wanted to go for his job at Melbourne”.[14]

The process seems casual by today’s standards. But the whole University then was casual by today’s standards and it was small and collegial as well. Although matters of probity were rigorously maintained, there were few formal procedures, fewer bureaucrats and no managers. Crawford, then Head of History, as well as Poynter, Harper, and Fitzpatrick, all held both Curti (Donna’s supervisor) and Bourke in the highest esteem. If he recommended Donna, the appointment committee would have endorsed that recommendation and moved as quickly as possible before the candidate could be snaffled by another institution. Norman Harper, who was visiting North America (he was a member of the Australian Delegation to the United Nations Assembly), came to see Donna in Chicago. He saw it as an interview for a lectureship; Donna’s impression was different: “I didn’t even realise that what I was really going for was a lectureship.”[15] It was a lectureship, it was offered to her, and she said yes.

It only remained for her to be released from her religious vows. In her case, unlike Greg’s, the process was smooth, “gently facilitated by the young priest who interviewed me”. She had been living without direct supervision for five years. In Chicago, she lived with four other women, all members of the Order, but all, like her, part of “this extraordinary crowd of women who were – in politics, church reform and race – moving ahead like fury”. For her, it was not a break from the Church but, rather, part of a movement of women “questioning the whole matter of whether virginity is higher than the married state”. “All I knew”, she later recalled, “was that I was happy to be going to Australia”.[16]

Donna arrived at Melbourne in July 1969: “D Day. Or DM Day”, Norman Harper wrote in his diary.[17] Donna was not, however, immediately comfortable in the Melbourne History Department. Looking back on those days – I arrived to take up a lectureship in French History four and a half years after Donna, in January 1974, the first new lecturer appointed to the Department since Donna – I wonder if she found it insular. Tom Griffiths reminds me that I myself wrote, in the sesquicentennial history of the Department, of finding it “a Department whose consciousness of its own history and traditions occasionally overwhelmed me”, a sentiment now lost to nostalgia but no doubt a valid shard of my feelings and, very likely, Donna’s at the time.[18]

Melbourne’s was an aging department. The new universities were recruiting younger academics, many, like Paul Bourke, from the old universities, which often lacked funds to replace them because their budgets were trimmed to help fund the new institutions. Like the University as a whole, the Department looked to Oxford and Cambridge to validate its graduates and send them back: Poynter and Crawford’s efforts to cast the net wider were just beginning to bear fruit. More particularly, Donna shared with Harper a feeling that, as she put it, “American History was not afforded the intellectual status of ancient, British and Renaissance History”. “Subtly”, she added, “its practitioners were not afforded that status either”.[19] But, sadly, she does not seem to have shared intellectual comradeship with Harper. They were, apparently, unable to bridge the gulfs of age, culture and intellectual orientation.

If Donna felt uncomfortable at Melbourne, she found support at the new La Trobe University (founded 1964), where Greg was already an exciting presence. Soon after her arrival, she joined the regular discussions Greg held with Inga Clendinnen, Rhys Isaac and others. Clifford Geertz called them the ‘Melbourne Group’;[20] others, more precisely, called them the Melbourne School of ethnographic history. At La Trobe, she also found warmth and welcome. Greg brought her into an informal group of progressive Catholics, ex-Catholics and sympathisers. It became, for Donna, a lifelong support group. Some of its surviving members were caring for her 52 years after her arrival in Melbourne.

Greg and Donna’s commitment to each other grew and, in mid-1971, they married. Paul Bourke witnessed for them both. Donna joined Greg at his modest house in Greensborough, a ten-minute drive from La Trobe. I was surprised to find that the only heating was a briquette stove in the lounge and the toilet was out the back door but, soon after, we bought a Fitzroy house without heating, though it did have an indoor toilet. Donna and Greg always lived modestly, but their heating and plumbing soon improved. In the same year, Greg was a surprise appointment to what was now named the Max Crawford Chair of History at the University of Melbourne.

In August 1973, I was in a French village, writing my PhD thesis, when I received a telegram from my sister. She had found a telegram at my parents’ house (they were on holiday) and copied out the text in her telegram. It was from Greg Dening, offering me a lectureship at Melbourne and asking me to telephone him urgently. Greg had, I later learned, written to Merle Curti, and Curti had sent him my CV and references and they had made the appointment on that basis. The 1973 oil crisis had slashed academic jobs and I decided to accept, but I couldn’t telephone Australia from the village. The only phone was in the post office, which was closed during the hours that Greg would be awake. I took the train to Paris. There I discovered that an Australian union ban would prevent any communication from France (it was the epoch of French nuclear testing at Moruroa Atoll). Fortunately, I stumbled on a sympathetic operator. I explained my situation; she routed the call through a Japanese colleague and I spoke to Greg.

These circumstances helped to turn the conversation in a personal direction. Greg didn’t seem like my boss. We started a correspondence (on typed aerogrammes). As I faced many issues, personal and academic, these entered the correspondence and Greg began to confide to me his religious past and his leaving the Church over Humane Vitae. That led him to tell me Donna’s story: how she too had been a member of a religious order excited about Vatican II; how he had met her owing to the Wisconsin connection, which, as he pointed out, she and I shared; and how Donna had come to Melbourne, how they had married and were now expecting a child. I shared in their anticipated joy, until I received a letter from Greg detailing Jonathan’s birth, his nine days of life, during which they stayed with him in hospital, and, finally, Jonathan’s death. Three decades later, Donna could confide in her friend Katie Holmes, that she “would have given everything” to care for Jonathan if he could have lived.

Through the fog of memory, I remember thinking that, unable to articulate his own grief, Greg displaced it onto Donna, saying that she was deeply afflicted but coping. My reply was horribly inadequate despite agony in writing it. We hardly spoke of this in person. But, in 2004, at the launch of Greg’s Beach Crossings: Voyaging Across Times, Cultures and Self, I brought my copy to Greg for his signature and reminded him of the custom that the author (and only the author) dedicates on the title page. “Not in this case”, said Greg, “it has to go on another page.” He signed the book, closed it and gave it to me. When I got home, I saw that he had signed below the dedication, which read:

For our son

Jonathan

A Memorial

He never knew us

His crossing was too brief

Greg’s inscription read, “To Chips. We’ve crossed many beaches together. I sign this book with love and affection. Greg Dening, July 2004.”

Early in the morning of 25 January 1974, my then wife and I crossed a beach, arriving at Tullamarine into a blinding sun. Greg Dening, John Foster, Robert Manne and Donna Merwick greeted us. Greg and Donna spent the day showing us around and initiating us into our new world. It was a searing hot day and we ended up walking along St Kilda Beach, Donna and I with our feet in the water as she chatted about Wisconsin. I found a moment to express sympathy at their recent loss and Donna accepted my clumsy words graciously.

Donna and I were now colleagues, young colleagues in an older department, Wisconsin graduates in an Oxbridge-oriented university and Americans in an Anglophile culture. Donna saw us as fellow outsiders, but I saw her as part of the establishment. When I arrived, Donna was teaching the fourth-year seminar, Theory and Method, which was central to the Honours program. She had only taken it over from Don Kennedy the year before but, to a newcomer, she seemed ensconced in this key position and, as she later recalled, she “never let it go”.[21]

I had only just been through my viva. Donna had revised her thesis and Harvard University Press had published it in 1973, under the title Boston Priests, 1848–1910: A Study of Social and Intellectual Change. In the book, she was, as she later put it, “enlarging the contribution of scholars such as Merle Curti in stressing the impact of social conditions on ideas”.[22] Presaging her subsequent ethnographic approach, she approached these priests in terms of the social system in which they operated. I thought the book superb cultural history; it took me into another world.

Soon after my arrival, I attended a seminar Donna gave on the will of a seventeenth-century Boston merchant. Robert Keayne had been excommunicated for having raised the price of nails after a shipwreck caused a shortage and then having sought to justify his unconscionable act on the grounds that the market governed prices. The Puritan theocracy adhered to the medieval doctrine of the just price. Keayne was forced to recant, but in his 158-page will he returned to the attack. Donna unravelled this moral tussle with remarkable skill. Like her close friend Rhys Isaac, Donna built on the work of Bernard Bailyn, but went much further. When she published her masterpiece, Death of a Notary, in 1999, I told her that I remembered her seminar on Robert Keayne as already showing how she could build a beautifully satisfying picture of one person’s mental universe and use it to bring us into another culture’s cosmology. She seemed pleased.

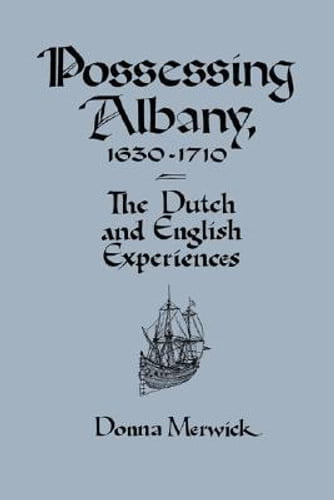

Donna was honing her intellectual approach, but she also moving into a new field, colonial New York. One day we were walking across the South Lawn. “I’m going to Dutch class”, she told me. She was learning Dutch to study early colonial New York. Struggling with new teaching and research demands, I was bowled over that Donna could embark on learning a new language alongside her undergraduate students. The first fruit of her efforts was a brilliant article she published in The William and Mary Quarterly in 1980, with the erudite but unassuming title, ‘Dutch Townsmen and Land Use: A Spatial Perspective on Seventeenth-Century Albany, New York’. It displayed her gift for analysing “the impact of social conditions on ideas” and indeed the ways that social conditions shaped what would soon be called mentalities. She showed that the Dutch and the English saw land in entirely different ways. “To a people [the Dutch] who displayed their wealth in movable property or in well-placed but intangible commercial connections, they [the English] brought a cultural system that displayed its wealth in country estates.”[23] Her analysis of this fundamental cultural difference, its ramifications for historical analysis and its impact on colonisation struck me as extraordinary then and on re-reading it today I am even more impressed.

In 1978, I returned from 14 months in France to find that Donna and Greg had finally left Greensborough and moved to Fitzroy. They bought a modest worker’s terrace house; unlike the Greensborough house, there was heating and the toilet was inside. Their new home was part of a former industrial site on Greeves Street that, as it happened, our then colleague Renate Howe was studying. It was nestled against one of the double-storey houses at each corner, houses which, Renate had discovered, were built for the clerks, whose wives could look down on the workers’ yards to ensure their compliance with regulations: wash on Monday, beat the rugs on Tuesday, etc. Donna and Greg were just around the corner and I occasionally knocked on the door. If I came late in the afternoon, Donna would say, “The sun is over the yard arm,” and we would drink a glass of sherry or, occasionally, a G&T. Sometimes we reminisced about Wisconsin or about our anti-war experiences, speculating on whether and when we’d crossed paths on demonstrations.

Often, however, the conversation turned to texts Donna had set for Theory and Method. It was then that I saw Greg and Donna as intellectual partners. In the department, they scrupulously avoided being seen together and they would never comment on points one of them made at meetings and seminars. But at home, over a drink, they would engage in profound, if loving, discussion of issues.

Donna had revolutionised Theory and Method. Instead of classic Oxbridge texts such as Collingwood’s The Idea of History, students were now reading contemporary scholars like Hayden White and Clifford Geertz. As we moved into the 1980s, Donna kept abreast with Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault and other French thinkers, whose works were just coming into fashion in the Anglosphere. Students in my French history subjects asked me about these texts. I had to work to catch up with them, especially on the more literary ones. Not long after its publication in English in 1979, chatting over G&Ts at Greeves Street, Donna waxed lyrical about Barthes’ essay on the Eiffel Tower. “Such a critic, such insight into the power of symbol”, she enthused. Donna argued that Barthes’ analysis of its cultural power was generally applicable. I had been amused by his extraordinary facility but I hadn’t taken him seriously enough. I went back to the essay and realised that by focusing on how we experience the tower, Barthes had taken us to the heart of the issue. It is what we experience, perceive and remember of reality that matters. Barthes had an eye for how we read things. I was reminded of the dictum attributed (probably wrongly) to Ledru-Rollin, a leader of the 1848 Revolution: “There go the people. I must follow them, for I am their leader.”

In the early 1980s, Greg and Donna bought two hillside blocks at Separation Creek, past Lorne on the Great Ocean Road, where they constructed a log cabin retreat. They loved to go there to write. It was their only luxury. Not too long after, they bought a house at 34 Stirling Street, Kew. Like Greeves Street, it was originally built for workers, but it was larger and more commodious. But it was too far for spur of the moment visits; there were no more afternoon chats over drinks.

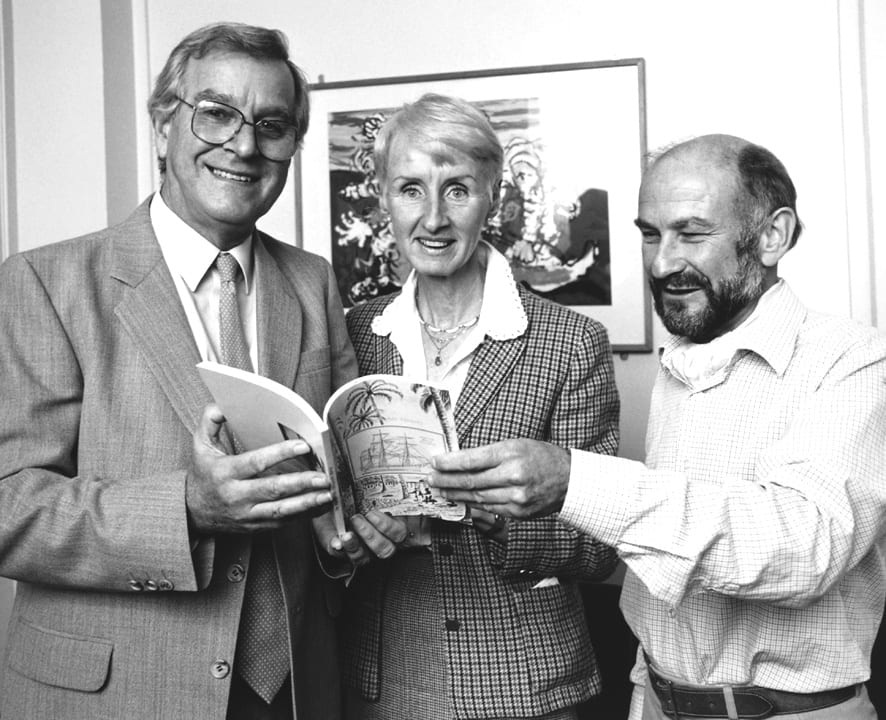

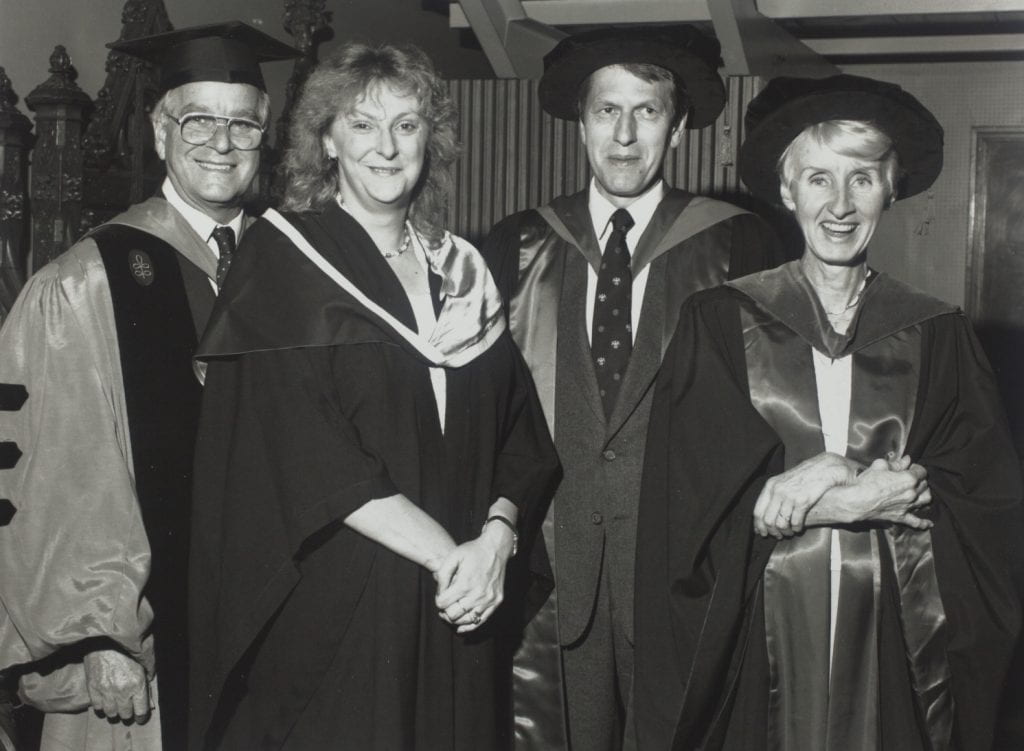

In 1983, Donna was diagnosed with cancer and was unable to work for several years. She fought through, however, and resumed work on the first of four path-breaking books which, as one reviewer noted, constituted “one of the most sustained and compelling inquiries into the life and culture of a single colony in colonial American historiography”.[24] Possessing Albany, 1630–1710: the Dutch and English Experiences (1990) developed the conceptualisation she had first formulated in the 1980 article ‘Dutch Townsmen and Land Use’ and extended its application across the time from the high point of Dutch culture in the New World to its erasure. This work, together with her many innovative articles, led to greater recognition and to Fellowships at Princeton University (1988–1989), the Rockefeller Center in Bellagio (1991) and Harvard (1993), all of which she thoroughly enjoyed.

Greg retired in 1990 and Donna devoted herself to organising and editing a tribute, published in 1994 under the title Dangerous Liaisons: Essays in Honour of Greg Dening. Even more than the 18 essays it contained, the book was a monument to Donna’s profound and enduring love for Greg.

In 1995, Donna herself retired. She found retirement immensely fulfilling. From 1998 to 2004, Donna and Greg spent summers at the ANU Centre for Cross-Cultural Research, teaching ten-day graduate workshops that became renowned for their intellectual excitement. When Donna talked about these workshops, I was transported back to our chats at Greeves Street.

In retirement, Donna completed the project she had conceived in the 1970s, writing three more major books, which, together with Possessing Albany, established her as both pioneer and leader in the study of the non-English past in North America and as theoretician of cross-cultural encounter.

Death of a Notary: Conquest and Change in Colonial New York (1999) was immediately recognised as a masterpiece. One reviewer concluded: “Prizewinning-caliber historical writing such as Death of a Notary is more than craft. It is art”. Another reviewer called it “a bold and creative work of history which forces the reader to adopt the ‘way of seeing’ which characterized the notary at the heart of her tale’”. Tom Griffiths’ beautiful essay on Donna’s work takes readers into her accomplishment, [25] but why not go directly to the text, as Donna always recommended? It is a beautiful and compelling read.

Death of a Notary and Possessing Albany together present a total cultural history of the previous colonial encounter, that between the Dutch and the English. Next, she turned to the encounter between the Dutch and the indigenous inhabitants of what the colonisers named New Netherland: The Shame and the Sorrow: Dutch-Amerindian encounters in New Netherland (2006).

She then turned to Peter Stuyvesant, a figure whose name all New Yorkers know (I grew up in a development called Stuyvesant Town) but whose tragic life, Donna argued, had not been understood in its context as shaped by Stuyvesant’s traumatic loss of the culture, which gave meaning to his life. The book ultimately took a different turn and became Stuyvesant Bound: An Essay on Loss Across Time (2013).

Before Donna got very far on this project, Greg suffered a massive stroke while they were walking in Tasmania. He was taken to the Royal Hobart Hospital, where he died on 13 March 2008. Donna’s initial shock and subsequent grief are beyond our ken, but Donna told Katie Holmes that she felt at peace about his death, and had a sense of his presence.

Supported by this feeling, by her faith and her friends, Donna rallied. She now preferred to be known as Donna Dening. Joy Damousi, then Head of what at that point was called the School of Historical Studies, suggested and raised funds for an annual lecture in Greg’s memory. Donna channelled some of her grief into this project. Tom Griffiths gave the first Greg Dening Memorial Lecture, on 11 December 2008.[26] In subsequent years, planning the Dening Lecture, with Ron Adams and Joy Damousi, was always a high point for Donna.

Nevertheless, even after her grief subsided, she found life less fulfilling without Greg. She joined our writers’ group for a time, sharing a chapter of Stuyvesant Bound, but found the night driving too difficult. In 2009, I think, she insisted Susan and I go to the Separation Creek house for Susan to recuperate from a procedure. “I don’t go there anymore, I don’t like the driving,” she said. The house gave us a healing space, but I was saddened to find it empty of the books and papers which had marked it as a hive of intellectual activity. She did go to the house on a few occasions, more it seemed out of necessity than for pleasure, but it was several years before she could bring herself to sell it.

Donna nevertheless worked assiduously on the book. In 2011, I told Donna that Susan and I were going to New York on our way to the 50th-anniversary reunion of my high school class. She insisted we visit Stuyvesant’s grave. Stuyvesant’s life was another case of catastrophic personal loss occasioned by enforced cultural shift, not only in his lifetime but also, indeed especially, in his subsequent treatment in history and myth. As Director of the Dutch colony of New Netherland, Stuyvesant had to surrender to the English in 1664. He returned to Holland to defend himself against the charge of failing to defend the colony and then returned to the city now called New York, where he died in 1672. He was buried beside his family chapel, on his own lands but in what had become enemy territory. In 1799 the Episcopal Church used the site to build a new church, St Mark’s in-the-Bowery.

In the 1950s, my uncle had been an organist at St Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery. I vividly remember turning the pages for him at Christmas performances of Handel’s Messiah. I thus had two reasons to make a visit there. As it turned out, however, St Mark’s evoked no memories for me. A terrible fire (started, like the fire that burnt down the University of Melbourne’s Wilson Hall in 1952, by a restoration workers’ acetylene torch), had nearly destroyed the church in 1978; the organ and all the ornate furnishings were gone, leaving a flat, empty space with stacks of plastic chairs. The grave, however, of which I had been ignorant in my youth, was indeed in the churchyard just as Donna had said.

Stuyvesant Bound was published in 2013. It won the 2015 Hendricks award from the New Netherlands Institute for the best book on New Netherland and the Dutch colonial experience. The book in its final form was a meditation on existence and loss through (mis-)representation. Donna eschewed empirical biography, instead evoking facts, texts and contexts to understand Stuyvesant in his time – and even more importantly, subsequently – as he became a key contested site of memory for opposing visions of the City of New York, of the American colonies and, ultimately, of the United States as a project. In this book, Donna confronted faith and belief more than in any other work. She came to terms with Stuyvesant’s stone-chiselled Calvinism, which drove his public and political conduct through empathy derived from her own confrontation with Catholic faith in all its forms.

In 2017, Donna fell on the bedroom floor at Stirling Street. Unable to reach her phone, she lay there for two days before her nephew Geoff Goonan found her. After a stay in hospital, supported by Virginia Kennedy and other friends, many from her early days in Melbourne, Donna needed to find a new residence. It had to be a Catholic home that offered daily mass. She moved into Mary MacKillop Aged Care in Hawthorn, which did indeed offer daily mass.[27]

Susan and I began to make monthly visits and take Donna to lunch. We tried a number of restaurants in the neighbourhood and finally settled on a funny little café/patisserie, the Linger Café, next to Camberwell South Anglican Church. Donna had long since ceased to eat a proper lunch. Linger Café offered extravagant pastries, which Donna found more than enough for lunch. Indeed, I don’t think she ever finished one of them. We gradually discovered that we were eating in the former Parish Hall. A plaque told us that it was named after the Rev C.R.C. Tidmarsh, the Founding Priest of the Church. We enjoyed the irony of this involuntary ecumenicism.

One day I stopped to peer into the church itself. Just as at St Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, the sanctuary had been emptied of pews, pulpit, lectern and organ, leaving only stacks of plastic chairs. Here, however, this was the result of changing theological orientations. The church, I noticed, had originally been St Mary’s Anglican Church. Donna enjoyed the story of the church’s evolution. Only now have I discovered that the reason the church decided to rename itself was that “the name ‘St Mary’s’ suggests the church is a Roman Catholic institution”.[28]

It is too late, sadly, to share with Donna the irony that a former Catholic religious found pleasure in a place renamed to avoid being taken for Catholic, but in this space redolent of its ecclesiastical origins, she felt comfortable. We spoke often of religious matters now. She was particularly attentive to the travails and triumphs of Pope Francis, which echoed, however faintly, the hopes of Vatican II that were inspiring Catholics when she and Greg first met.

Donna was finding fulfilment in a personal project, preparing for publication her journal of a visit to the Marquesas she made with Greg during the summer of 1974–1975. Greg wrote extensively about this visit in Beach Crossings but did not mention Donna.[29] As in the Department, they normally projected separate professional lives and, indeed, travelling together on such a trip was unusual for them. Ron Adams persuaded Donna to publish the journal and Joy Damousi wrote a foreword. Donna gave the book a title evocative of the works of many voyagers to the Marquesas: The Marquesan Journal of Donna Merwick Dening: December 1974–January 1975. It was her last project.

During the pandemic, I was often unable to visit Donna. In February of this year, I did get to see her, but she didn’t feel up to going to the Linger Café as we had done so often. She spoke then of wanting to visit Greg’s grave. To my surprise, she couldn’t remember the name of the cemetery. I promised to arrange a trip. I hadn’t been in Australia when Greg died, so I checked with Charles Zika, who had brought their car back from Hobart after Greg’s death. He told me that Greg was buried at the Anderson’s Creek Cemetery in Warrandyte. Donna agreed on a date for the trip, but the day before told me she didn’t feel up to it. This happened several times. Then we were back in lockdown and no trip was possible. I had forebodings that she was withdrawing.

I began making sure I called once a week. Our conversations became shorter. Brief answers to my questions about her state, which gradually took a downward turn: “How are you feeling?” “Not very well today. How’s Susan? How’s her book going?” Once answers supplied, she would “call me next week” and then take a closing tone. One week, I couldn’t get an answer. After trying a number of times, I learned that she had been briefly hospitalised. Ron Adams told me that she spoke to him from St Vincent’s Hospital and told him, characteristically, “Ron, I think I’m dying. But I don’t want you to be worried”. Back at Mary MacKillop, she rallied enough to say goodbye to Ron. He was the last person to whom she spoke. She died on the following Sunday, 22 August.

On Thursday 26 August, a funeral mass was held at the Home. Donna was buried with Greg at the Anderson’s Creek Cemetery. The service was limited to ten and I wasn’t there, but Donna’s friend Mary Ryllis Clark sent me the moving eulogy she delivered. Donna’s death was observed in accordance with the rites she had learned in another continent at another time, a cultural continuity that transcended the many crossings she had made. A peerless analyst of cultural crossings, she kept her own continuities in death.

* * *

On a sunny afternoon in the summer of 2012, I interviewed Donna at some length. Susan and I had been asked to select and write biographical notices on leading Australian women historians for the Dictionnaire universel des Créatrices.[30] It was a joy to come to terms with Donna’s career from the beginning. The scope of the entry meant that we had to cut much of what we wrote initially, but in working through the material I was overwhelmed at the scope of Donna’s accomplishment. Her study of the Dutch-English colonial experiences, in works of great erudition and highly innovative conception, transformed the field by showing it to be a site of continuing colonial three-way encounters. By putting the ensuing cultural ruptures at the forefront of her analysis and by showing how they impacted on individuals as well as on peoples, she brought home the tragic consequences of colonialism. And she did all this researching on her own from the other side of the world.

Charles Sowerwine

Sunday, 17 October 2021

You can read more on Donna Merwick in Charles Sowerwine and Susan Foley’s entry on Donna in The Encyclopedia of Women and Leadership in Twentieth-Century Australia, as well as David Goodman and Mike McDonnell’s interview with Donna, referenced in the article. Greg Dening’s obituary, also written by Charles Sowerwine, can also be found on Forum.

Join us for the 2021 Annual Greg Dening Lecture ‘Performances on the World Stage: Interpreting Iron Innovation ‘In the Light of What is Old’ by Jenny Bulstrode (UCL) on 27 October at 6.15pm.

Download a pdf version of this article: Donna Merwick Dening A Reminiscence by Charles Sowerwine.

Sources

Adams, Ron ed. The Marquesan Journal of Donna Merwick Dening: December 1974–January 1975. Redland Bay: Connor Court Publishing, 2020.

Anderson, Fay. An Historian’s Life: Max Crawford and the Politics of Academic Freedom. Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press, 2005.

Bailyn, Bernard. ‘The Apologia of Robert Keayne’. The William and Mary Quarterly 7, no. 4 (1950): 568–587.

———. The Apologia of Robert Keayne; The Last Will and Testament of Me, Robert Keayne. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1965.

———. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 1967.

Dening, Greg. Beach Crossings: Voyaging Across Times, Cultures and Self. Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Publishing, 2004.

Geertz, Clifford. ‘History and Anthropology’. New Literary History 21 (1990): 321–335.

Goodman, David. ‘“There Is No-One to Whom I Can Talk” – Norman Harper and American History in Australia’. Australasian Journal of American Studies 23, no. 1 (July 2004): 5–20.

Goodman, David and Mike McDonnell. ‘An Interview with Donna Merwick’. Australasian Journal of American Studies 34, no. 1 (July 2015): 60–83.

Goodman, David and Donna Merwick. ‘American History at Melbourne: A Conversation’. In The Life of the Past: The Discipline of History at the University of Melbourne 1855–2005, edited by Fay Anderson and Stuart Macintyre, 279–295. Melbourne: Department of History, The University of Melbourne/RMIT Publishing on Informit Library, 2006.

Griffiths, Tom. ‘History as Art: Donna Merwick’. In Tom Griffiths, The Art of Time Travel: Historians and their Craft, 196–219. Carlton, Vic: Black Inc, 2016.

———. History and the Creative Imagination: The Inaugural Greg Dening Annual Lecture, The University of Melbourne, 11 December 2008. [Melbourne]: The School of Historical Studies, The University Of Melbourne, 2009.

Merwick, Donna. Boston Priests, 1848–1910: A Study of Social and Intellectual Change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973.

———. ‘Changing thought patterns of three generations of Catholic clergymen of the Boston Archdiocese from 1850 to 1910’. PhD Thesis, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1968.

———. ‘Crawford and Merle Curti: Their Friendship and Their Correspondence’. In Max Crawford’s School of History: proceedings of a symposium held at the University of Melbourne, 14 December 1998, edited by Stuart Macintyre and Peter McPhee, 79–87. Parkville, Vic: Department of History, The University of Melbourne, 2000. , pp.

———, ed. Dangerous Liaisons: Essays in Honour of Greg Dening. Parkville, Vic.: History Dept., University of Melbourne, 1994.

———. Death of a Notary: Conquest and Change in Colonial New York. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999.

———. Possessing Albany, 1630–1710: The Dutch and English Experiences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

———. The Shame and the Sorrow: Dutch-Amerindian encounters in New Netherland. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

———. Stuyvesant Bound: An Essay on Loss Across Time. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

Poynter, John. ‘“Wot Larks to be Aboard”: The History Department 1937–71’. In The Life of the Past: The Discipline of History at the University of Melbourne 1855–2005, edited by Fay Anderson and Stuart Macintyre, 39–92. Melbourne: Department of History, The University of Melbourne/RMIT Publishing on Informit Library, 2006.

Smith, Barry, and Pat Jalland, ‘Bourke, Paul Francis (1938–1999)’, Obituaries Australia, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

Charles Sowerwine. ‘Greg Dening (1931–2008)’. Australasian Journal of Irish Studies 7 (2007/8): 3–7.

———. ‘Modern European History in the Antipodes’. In The Life of the Past: The Discipline of History at the University of Melbourne 1855–2005, edited by Fay Anderson and Stuart Macintyre, 207–233. Melbourne: Department of History, The University of Melbourne/RMIT Publishing on Informit Library, 2006.

——— and Susan Foley, ‘Merwick, Donna’, in Le Dictionnaire universel des Créatrices, eds Béatrice Didier, Antoinette Fouque, Mireille Calle-Gruber (3 vols; Paris: Éditions des Femmes, 2013); [English version:] ‘Merwick, Donna’, in Judith Smart and Shurlee Swain, eds, The Encyclopedia of Women and Leadership in Twentieth-Century Australia. Melbourne: Australian Women’s Archives Project 2014.

Footnotes

[1] I warmly thank Ron Adams, Mary Ryllis Clark, Joy Damousi, Susan Foley, David Goodman, Katie Holmes, Virginia Kennedy, Catherine Kovesi and John Poynter for their suggestions and comments on drafts.

[2] Mundelein was incorporated into Loyola University following affiliation in 1991. Donna would have appreciated that, in 1989, the College initiated a Peace Studies Minor, which ‘integrated feminist perspectives’, and this program was transferred to the Loyola curriculum.

[3] David Goodman and Mike McDonnell, ‘An Interview with Donna Merwick’, Australasian Journal of American Studies 34, no. 1 (July 2015): 61.

[4] Fay Anderson, An Historian’s Life: Max Crawford and The Politics of Academic Freedom (Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Press, 2005): 190–191.

[5] Donna Merwick, ‘Crawford and Merle Curti: Their Friendship and Their Correspondence’, in Max Crawford’s School of History: Proceedings of a Symposium Held at the University of Melbourne, 14 December 1998, eds. Stuart Macintyre and Peter McPhee (Parkville, Vic: Department of History, The University of Melbourne, 2000), 79–87.

[6] Anderson, An Historian’s Life, 239; Merwick, ‘Crawford and Merle Curti’, 79–80.

[7] Goodman and McDonnell, ‘An Interview with Donna Merwick’, 63.

[8] Ibid.

[9] John Poynter, ‘“Wot Larks to be Aboard”: The History Department 1937–71’, in The Life of the Past: The Discipline of History at the University of Melbourne 1855–2005, eds. Fay Anderson and Stuart Macintyre (Melbourne: Department of History, The University of Melbourne/RMIT Publishing on Informit Library, 2006), 69.

[10] Ibid., 81.

[11] Greg Dening gives a detailed account in Beach Crossings: Voyaging Across Times, Cultures and Self (Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Publishing, 2004), 106–110.

[12] Ibid., 111–112.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Goodman and McDonnell, ‘Interview with Donna Merwick’, 63.

[15] Ibid.; Poynter, ‘“Wot Larks to be Aboard”, 76.

[16] Goodman and McDonnell, ‘Interview with Donna Merwick’, 63–65.

[17] David Goodman, ‘“There Is No-One to Whom I Can Talk” – Norman Harper and American History in Australia’, Australasian Journal of American Studies 23, no. 1 (July 2004): 17.

[18] Tom Griffiths, ‘History as Art: Donna Merwick’, in The Art of Time Travel: Historians and their Craft (Carlton, Vic: Black Inc, 2016), 198; Charles Sowerwine, ‘Modern European History in the Antipodes’, in The Life of the Past, eds. Anderson and Macintyre, 198.

[19] David Goodman and Donna Merwick, ‘American History at Melbourne: A Conversation’, in The Life of the Past, eds. Anderson and Macintyre, 284.

[20] Clifford Geertz, ‘History and Anthropology’, New Literary History 21 (1990): 325.

[21] Goodman and McDonnell, ‘An Interview with Donna Merwick’, 67.

[22] Goodman and Merwick, ‘American History at Melbourne’, 284.

[23] Donna Merwick, ‘Dutch Townsmen and Land Use: A Spatial Perspective on Seventeenth-Century Albany, New York’, The William and Mary Quarterly 37, no. 1 (1980): 75–76.

[24] Griffiths, The Art of Time Travel, 212.

[25] Griffiths, ‘History as Art’, 196–219.

[26] Tom Griffiths, ‘History and the Creative Imagination: The Inaugural Greg Dening Annual Lecture, The University of Melbourne, 11 December 2008’ ([Melbourne]: The School of Historical Studies, The University of Melbourne, 2009). All Greg Dening Lectures are republished in the Melbourne Historical Journal.

[27] It became ‘St Vincent’s Care Services Hawthorn’ in 2020.

[28] “Late 2013 – a new name for the church”, “During 2014 – student ministers appointed; congregation numbers grow; church reconfigured”. Camberwell South Anglican Church, Timeline.

[29] Greg Dening, ‘Being There’, in Beach Crossings: Voyaging Across Times, Cultures and Self (Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Publishing, 2004), 55–98.

[30] Charles Sowerwine and Susan Foley, ‘MERWICK, Donna’, in Le Dictionnaire universel des Créatrices, eds Béatrice Didier, Antoinette Fouque, Mireille Calle-Gruber (3 vols; Paris: Éditions des Femmes, 2013); English version: ‘Merwick, Donna’, in The Encyclopedia of Women and Leadership in Twentieth-Century Australia, eds Judith Smart and Shurlee Swain. Melbourne: Australian Women’s Archives Project 2014).