Introducing 2022 Hansen Scholar in History Ines Jahudka

The Hansen Trust, established to advance the study of History at University of Melbourne, includes an annual PhD scholarship to the doctoral program in History in SHAPS. The 2022 recipient, Ines Jahudka, is researching the role of the layperson in the early modern English postmortem process. She is interested in the cultural histories of medicine, sickness and death, particularly the role of poisons. Ines was also the recipient of the 2021 Felix Raab award for the best student essay on early modern European history. We sat down to speak with Ines about her research and her aspirations.

Tell us a bit about your project.

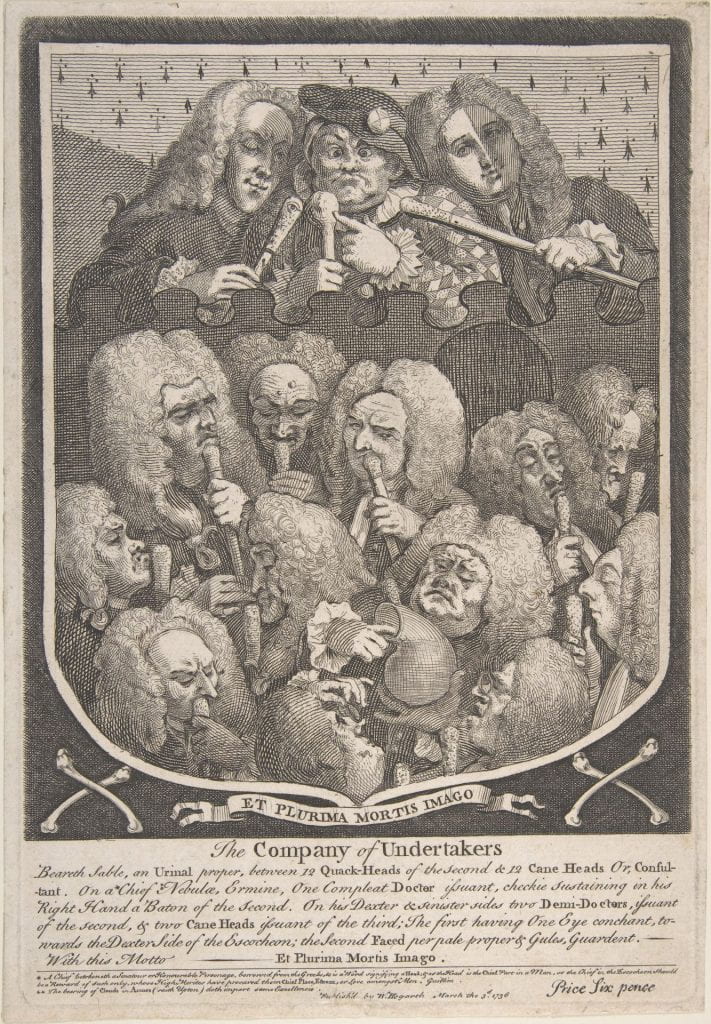

My research is looking at the role played by ordinary people in the postmortem processes in early modern England (so, from the 1500s to the early 1800s). This is a time before the police force was developed and before centralised records were kept. Forensic medicine was still based on the Galenic system and there wasn’t a medical ‘profession’ as such. Who, then, decided how someone had died, if there might be someone responsible and who that person might have been?

What I have found is that local people without formal medical training played a significant role in making decisions about death or dead bodies. The local Searchers of the Dead, for example, were a pair of local women who would be called to examine a body and, often, it was these women who would declare the cause of death for the official parish records. Inquests were a community event which anyone could attend. They were presided over by the coroner, a local man who usually did not have any medical or legal training. The body itself was present in the inquest room for the jury and the coroner to inspect and draw their own conclusions. Gender, class and religion play a huge role, as cultural understandings of appropriate behaviour influenced how the jury might have felt about the defendant or the victim.

My research draws together the cultural histories of sudden or violent death with social histories of medicine and law. It’s also a really fascinating look at how, who or what we consider to be an expert has changed, going from someone who could (like a sailor recognising a drowned body) to someone who was (a doctor, or a surgeon). This shift reflects how the increasing commodification of knowledge in the eighteenth century cemented the status of the (male) professional.

What kinds of sources are you using? What are the challenges you face?

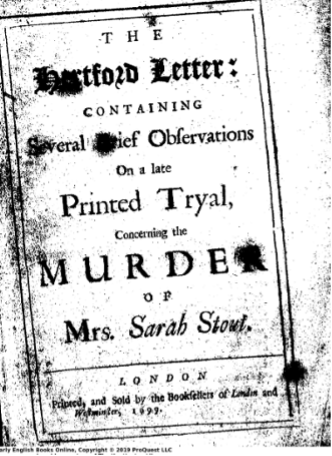

I’m pulling my information from a variety of different sources: primarily, records of the law court and coroner, along with parish account books and burial records. There were also quite a few cases which aroused a great deal of public discussion which usually means diary entries and, if I’m lucky, pamphlets printed about the trials.

There’s also so much information about medical knowledge in self-help guides printed at the time, which of course influenced the way witnesses and the men of the jury thought about the death, and give insights into the forensic process.

The challenges for me are pretty common for all historians of the era: women and people of lower socioeconomic standing are almost invisible from the records! This means using more sources and trying to re-create their role in the postmortem process from the merest scraps of information and being careful not to build a distorted picture. To be honest, another big challenge is emotional: some of these cases are often desperately sad or horrifically violent – so, they can be really hard to read.

What is it that drew you to history as a field of study?

I had every intention of majoring in linguistics when I first enrolled at Melbourne Uni. Then, in first year, I spotted a history subject about medieval heresy, disease and witchcraft which sounded pretty interesting. The subject was a revelation: it was not a recounting of plagues or witch-burnings, but an illustration of the way that history investigates the diversity of the human experience, and how these experiences of the past have shaped the world around us in the present. Furthermore, the way we explain the past (and, therefore, the present) is continuously evolving. I took many other history subjects which not only challenged me to think about different historical eras or cultures but also about different approaches and methods. This, in turn, has made me consider how I want to engage with history in the future, and how and with whom I want to communicate those histories. Fittingly, my doctoral supervisor is Jenny Spinks, who taught the first-year subject that sparked my obsession with history.

The general public often seems to think that history is something that happened in the past to someone else; it’s interesting, particularly if it’s being done by sexy Vikings or well-dressed Regency debutantes, but not really relevant to the world today. It’s a story without a connection. Studying history, though, makes us aware of how we can find meaning from the past in almost everything that we do or think. It shows us how we are simultaneously profoundly different from and just the same as people in past eras. I recently found an anonymous pamphlet printed the early 1500s which was complaining about lockdowns in plague-struck London: the arguments against forced quarantines were identical to those floating around social media over the past few years!

What has it been like returning to historical studies as a mature age student?

To be honest, it’s one of the best things I’ve ever done in my life. I didn’t have the opportunity to go to uni when I left school but, hey, I’m here now! It’s so exhilarating and challenging to be surrounded by so much knowledge and being exposed to so many different points of view. I’ve made some really great friends – people who, like me, have returned to study after some time in the workforce. I’ve also met some of the most interesting and engaging people who are much younger than I am but have made such an impact on how I think about myself and my studies. It’s been a really fantastic experience.

What advice would you give to first-year undergrads considering doing a history major?

Keep an open mind, particularly when it comes to picking your subjects! Everything has the potential to add depth to the way you look at history and the ways you can interpret your favourite era. You may discover new favourite eras! We don’t exist in one dimension, so the way we look at how people lived in the past shouldn’t be one-dimensional, either. Everything helps, not just to make you a more knowledgeable person, but to add depth to any project you take on in your history journey. Embrace your breadth subjects and expand the ways you can think about the past. You will become a stronger student and a more well-rounded historian.

What does receiving the Hansen scholarship mean to you?

It is immensely gratifying to know that not only can I do well at Australia’s premier university, but I have something worthwhile to say, something to contribute to the study of history; and this ability has been recognised. I am so excited and proud to have been selected as the recipient of the award, firstly for the prestigious nature of the award, and secondly, for the generous financial support that the scholarship offers. I hope to use my historical training to further public engagement with history and having the Hansen scholarship on my CV will add weight to my voice when my dreams of publication (hopefully) come to fruition.

The Hansen Trust Scholarship in History provides $35,000 per year for the length of a full-time PhD candidature. A key feature of the scholarship is a mentoring program that provides valuable experience in tertiary teaching and the promotion of History to the community.

Applications for the next round of Hansen Scholarships in History are currently open.

Applications close 7 November 2022.