Dr Donald Edward Kennedy (1928–2021)

This week marks one year since the passing of Dr Don Kennedy, who taught History at the University of Melbourne from 1958 until his retirement in 1993, and later retained a strong connection to the University as Principal Fellow. His former students and colleagues Dolly MacKinnon, Alexandra Walsham, Amanda Whiting, and Wilf Prest look back on his life and legacy in this tribute.

Born in Surrey Hills, Melbourne, in 1928, Don Kennedy was educated during the lead-up to and against the backdrop of World War II and its aftermath. He received a scholarship to Scotch College, Melbourne, in November 1941. His undergraduate degree in English and History commenced at The University of Melbourne in 1948. He graduated at the Old Wilson Hall in 1951 with a first in both History and English.[2] This combination of English and History would endure throughout Don’s career. It was as a poet that Don was first published in The Melbourne University Magazine between 1950 and 1953. A full list of his publications appears at the end of this tribute.

Don’s undergraduate education played out against “war-time shortages”, which included “critical textbooks not available to order”.[3] Working part-time at the University Library as an undergraduate, he found some books that had been purposefully misshelved in order to guarantee exclusive access to the culprit. High-demand books were only available for two-hour loans within the confines of the library. Hence, Don’s generosity with his own books to his students over the five decades of his teaching came from his experiences of a lack of access. The Melbourne University he first encountered in the late 1950s was “small-scale, traditional, and gracious”, with “open spaces”, “detached professors’ houses (fronting Professors’ Road)”, and a tennis court. All of these would make way for the Baillieu Library, and the Medical Building, the first of many features of the university’s perpetual cycle of expansion and regeneration.[4]

His MA, titled ‘Some Aspects of Causation in History: An Inquiry into the Logical Efficacy of the Causal Presupposition in Historical Explanation’, supervised by Arthur Lee Burns, was completed in 1952.[5] This time Don graduated in the Union Theatre, as the new Wilson Hall was not yet complete. He said graduands had to “walk the plank” over the orchestra pit to reach the stage![6]

He was appointed as Senior Tutor in 1953. Don was also awarded a University of Melbourne Travel Scholarship to the University of Cambridge and received a postgraduate research scholarship to Trinity College. At Cambridge he continued to publish his poetry, first in The Trinity Magazine (1954) and then Granta (1956). He completed his PhD, entitled ‘Naval Administration During the Civil War and the Fleet Revolt of 1648’. Don studied under Professor Brian Wormald (Peterhouse), a scholar of Clarendon and, also, Peter Laslett of The World We have Lost fame, which would later frequently be cited in Don’s lectures. His supervision experiences did not make a great impression upon him and, so, Don focused on his close primary and secondary source readings. Archives from the seventeenth century would underpin his study. Acquiring the palaeographic skills that were necessary to decode them, not formally taught as part of the degree, became his focus. An archivist at the UK Public Record Office, Chancery Lane, helped him unravel an aspect of the seventeenth-century script – but Don taught himself the rest. Teaching palaeography as a critical skill would become a hallmark of his teaching career, his enduring gift to generations of students that he would teach.

In 1957, he returned to Australia by ship to take up the post of Tutor in History at the University of Adelaide. He was also Vice-Master of St. Mark’s College at that university. He returned to Victoria in 1958 having been appointed to a lectureship in History at The University of Melbourne. It was in that year he also won the Sir Julian Corbett Prize in Naval History at the University of London. Emeritus Professor Wilf Prest remembers taking Don’s “superbly organised lectures and tutorials” in British History, which he described as “godsent”, recalling

a blackboard taxonomy of the politico-religious groups involved in the Putney and Whitehall debates … Grandees and Agitators, Independents, Levellers and Fifth Monarchy men … we spotty freshers (… addressed by title and surname) could not help feeling more than a little in awe of the be-gowned, dapper, goateed and immensely fluent Dr. K.[7]

Don retained his practice of formal greetings throughout his teaching career.

Don progressed rapidly through the ranks, becoming a Senior Lecturer (January 1963), Reader/Associate Professor (1966) and then a sub-Dean. Following his retirement in 1993, Don became a Principal Fellow in the School of Historical Studies. One of his closest colleagues and friends was Ron Ridley. On their first meeting, Ron vividly recalls: “we instantly hit it off, recognising serious mutual commitment to real education.” Don would also be “someone I turned to often to save my sanity and academic life – and he never let me down. He was also quite fearless in putting his name to protests against unprofessional behaviour at the highest levels.”[8]

Don’s professional life developed against the aftermath of World War II, the later Vietnam War and conscription debates, and the Indigenous Referendum (1967). Each event marked seismic transgenerational shifts and conflicts in the social, cultural and religious attitudes towards war and politics, both outside and within the academy in Australia. The second half of the twentieth century saw the tertiary sector subjected to what became increasingly rapid reforms and the quasi-corporatisation that continues apace today.

Within the continuity and change over his career, he delighted in advancements in technology, and the democratisation of the archives as he saw it. Great celebrations accompanied the joint purchase of the Short Title Catalogues and accompanying microfilm of early modern texts: The University of Melbourne bought the index and Monash University bought the microfilm. Later still they were accessible online by a university subscription to Early English Books Online and Don would marvel at these technological advances. He had conducted his early research in person and with the use of an extensive index card system. In fact, his handwritten lectures and letters were a hallmark of his interactions with his students. Dr Mark Nicholls remembers:

I still have at least one letter from him – again incredible – writing, in long hand, to me at my home address enquiring after my health – gently implying that I was a.w.o.l. from P[alaeography] & D[iplomatic].[9]

The world Don had found on entering the History Department in 1958 was radically different by his retirement in 1993. His last lecture was well attended and it was fitting that Dr Mark Nicholls went to it the year he started teaching. Don had also given Mark his first opportunity to lecture, as was the case with many of his postgraduates. At Don’s retirement dinner held at University House, Professor Ron Ridley gave the eulogy in the Lower East dining room. Ron describes this as “a very great honour, attesting to our close links. Don ensured that I inherited his room (the best in the department), where I also inherited the desk, originally [Professor] Max Crawford’s (1906–1991), then Don’s, then mine”.[10]

Don’s life then turned to further embrace the delights of family life with Bev (1947–2021), their children Sarah, Liza, Susannah and Rod and, later, grandchildren. Aspects of the academic world were lost but others were re-made in new research interests and ventures. After his retirement Don continued to supervise his remaining postgraduates and to write.

Don will forever be associated with lecturing in British History. He was taught British History by Associate Professor Kathleen (Katie) Fitzpatrick (1905–1990), and his tutor had been Owen Parnaby (1921–2007), who became Master of Queen’s College (1966–1986). In turn, Don would take over the mantle of British History from Kathleen Fitzpatrick.[11] For a greater part of this time, he shared the course with his colleague Laurie Gardiner (1925–1990), who had joined the department in 1959. They formed a teaching team which colleagues called the ‘dynamic duo’. Their course, as Don reflected, “came intuitively from opposite sides of the royalist-puritan divide”. Mark Nicholls remembers a striking line from the ‘Putney Debates’ that “will stay with me forever”: the right to “starve unmolested in the public highway”. An entry from the Student Counter Handbook described Don as “a man totally at home in the period, with a darting eye and sparkling (sometimes biting) tongue”.[12]

Another Student Counter Handbook entry described Laurie Gardiner as “the most entertaining lecturer I ever had”.[13] A dynamic duo indeed! Debate amongst students also focused upon which side in the Civil War Don favoured. Mark Nicholls’ speculation is illuminating:

Once Geoff Smith came up to present a paper on his thesis and DEK kindly invited some of us former students … to a pate and wine luncheon in his office. When DEK remarked that Geoff had cultivated a nest of Royalists among us, with one exception, we took this opportunity to quiz him on his civil war allegiances – of which he had left us guessing all year. I proposed that I was at Nottingham with Charles that August in 1642 – where was he? “At sea” was all he gave us. We took this to imply he was for Parliament.[14]

This joint teaching relationship in the British History courses only ended with Laurie’s retirement in 1990, followed by his premature death from cancer.[15] The British History course would be modified from a two-semester course to a single-semester one, but it continued in the history curriculum at Melbourne into the 2000s, well after Don’s retirement in 1993.

When Dolly MacKinnon delivered the course as a casual lecturer in 2003, Don graciously agreed to give a guest lecture. Once more he captivated students with what Alex Walsham described as his evocation of puritan zeal. In that class students eagerly asked questions and viewed the artefacts he had brought to class: a double-sided seventeenth-century woodcut, The Orthodox True Minister and The Seducer and False Prophet. An original “hand-written inscription” stating “The Rev. J.C. – a friend to truth, 1648”, appeared above that image of The Orthodox True Minister, making this for Don, “all the more precious”.[16]

The Seducer and False Prophet was used on the cover image for Don’s book Grounds of Controversy (1989), discussed below. Alex remembers in one of his most memorable lectures – regularly repeated – he re-enacted the biblical story of the zeal of Phineas in Numbers 25:1–18, who took up a javelin or spear and thrust it through the body of the Israelite man and the belly of the Midianite woman who were copulating in transgression of divine law. What he conveyed – without the aid of slides or PowerPoint presentations on which lecturers now rely – through the sheer force of his imagination was the fire that raged in the bellies of the hotter sort of Protestants with whom he clearly felt an affinity.

As Don reflected on his career, he saw University curricula were simultaneously fragmenting and becoming more interdisciplinary and, so, he became involved in interdisciplinary seventeenth-century studies and studies in war and peace. For instance, he co-taught with a colleague in the English department a course on seventeenth-century literature, which included the writings of John Milton and Sir Thomas Browne, and another called Peace and Conflict.[17] His ear for the language of the period was acute and his own prose mimicked its rhythms. Another interdisciplinary colleague Professor Tony Coady recalls:

It was a great experience working with outstanding scholars from History, English, Politics and Economics. Through that experience during the Peace and Conflict years, Don and I became good friends, and remained so thereafter, and indeed were near neighbours. He was a much warmer and good-humoured person than his sometimes rather aloof manner could suggest. He is greatly missed.[18]

Professor Emeritus John Poynter recalled that Don had written “a thoughtful paper setting out the progress in technical skills he thought a student should acquire”, although his suggestions were not taken up by the department.[19] At this time, Don humbly noted,

I also introduced an honours course in Puritanism, which, together with Paleography and Diplomatic (the study and interpretation of original scripts and manuscripts), was perhaps the most exciting and productive teaching venture of my career.[20]

Emeritus Professor Ron Ridley considered Palaeography to be Don’s “signature course”:

This was the dream course: he took students who knew nothing, and taught them total competence in a most complicated skill, which they came to love totally … They each finally as their project had to choose a totally unpublished document, transcribe it, translate it, and write a full commentary on all points of interest!![21]

Don never judged, but rather he guided, and those who learned to branch out, flourished.

For Helen Penrose, ‘Dr Kennedy’ was “one of the most inspirational teachers” in her life.

His Honours course lit a fire in my mind and set me on my course as a professional historian. He taught me the thrill of how to approach and know, intimately, original sources. His teachings will continue to go with me into the archives of each new organisation I write about. I feel deeply privileged to have been one of his students.[22]

Dolly also took his palaeography course and taught palaeography at each of the three Australian universities she worked at over her three-decade career, in both music and history. The art of Palaeography always worked its magic.

A recurring theme offered up by his former students was that Don “taught me to think as a scholar and a historian”.[23] So much so that, as Dr Damian Powell, Principal of Janet Clarke Hall, concluded, “I became an historian – indeed, I became a British historian – because of Don Kennedy”.[24] For Don “the study of history” was “a serious and demanding business”.[25] “Dr Kennedy (never Don) saw his task as encouraging and equipping us to learn, and learn deeply, about his subject matter”, for history was a vocation.[26]

As Associate Professor Amanda Whiting, who tutored for Don in British History, so eloquently puts it:

he did not tell us how to do history … what … he did was to listen with his poet’s sensibility for the rhythm and sounds of words as much as their meaning, and then transmute the base stuff of a student’s … poorly articulate comment or question … into the gold of a probing inquiry or deep insight. … It was his insight, but he gave it back to us as our own, and we grew with confidence through these exchanges.[27]

He taught Dr Deb Hull, and many others, “how to hear split infinitives”.[28] Dolly remembers one exchange regarding her spelling, which was better suited to the early modern world, where phonetics abounded. With a combination of his serious face and smiling eyes, Don asked if she was “really interested in historical ‘sinuses’ or might he suggest ‘sinews’ instead?” His quick repartee was a regular feature of his interactions with colleagues and students alike. At a graduation ceremony for one of his PhD students, Don quietly murmured, “How gaudy the Oxford gown was!” to his colleague Associate Professor David Philips (1946–2007), implicitly contrasting it with the more restrained academic dress characteristic of Cambridge – known as “the other place” from which he had graduated. This is a well-known phrase used by Cambridge University about Oxford University. David laughed, rising to the bait and launching into a good-humoured defence! Deb Hull remembers overhearing the conspiratorial, hushed exchanges between Don and Ron during Brown Bag Seminars in History.[29]

Don’s office was in the corner of the third floor of the West Tower of the Medley building and comprised a room lined with cupboards, surmounted by bookcases which rose to the ceiling, pierced only by the light from two long windows that flanked either side of his desk. On each shelf, as Senior Lecturer Dr John Reeve observed, “his books sprouted yellow annotated tabs as his ideas were refined over years, often in class; he delighted in finding exactly the right word to express his view; and he was always sensitive to what he called ‘the elusive quality of the human spirit’”.[30] There was always an aroma of old books mixed with pipe tobacco that came with the books he gave us to take away to read. As Mark Nicholls observed, “the smoker’s drawer” of Don’s desk “was a marvel of the past we shall never see again”.[31]

Supervisions were intense affairs, where arguments were tested and queried, “Miss Whiting, are you suggesting … ?” And, then, as Amanda noted, “occasionally, the point would be underscored by a slightly raised index finger. When you got one of those you knew you had his full attention, and probably you were on the right track too”.[32] John Reeve recollected that Don “enjoined his students always to ask the question: ‘By what authority do I speak?’”.[33] Alex Walsham, now Professor of Modern History, Cambridge, recalls that Don

could also be gnomic, cryptic and sometimes even (to a novice scholar very unsure of herself) completely unfathomable. Not infrequently I came out of supervisions not knowing whether I had done well or badly. He didn’t tolerate intellectual flabbiness, and nor did he kowtow to scholarly fashion, greatly to his credit. What he valued most was the capacity to think deeply and to commune with an alluring but elusive past.[34]

Mark Nicholls remembers that “when I proposed my thesis topic, which eventually became something on Bevil Grenville, he congratulated me that I had avoided the ‘all too common temptation to write a thesis on the Meatworks of Manangatang’”![35]

To undergraduate students, he could also appear a formidable character. As Emeritus Professor Charles Zika observed when he transferred as an undergraduate into “a History Major in third year without the prerequisite subject on … British History … contrary to the quite erroneous suggestions of some fellow students, Don welcomed me immediately.”[36] This seminar included Laurie Gardiner, and the Professor of Church History at Ormond Theological College, George Yule. Their classes were defined by lively polemic![37]

As mentioned, Don’s formal greetings were legendary. Formal introductions comprised our first encounters with each other as students and then punctuated the intellectual engagement and disputations that followed. Only once outside the formality of the classes would we then reintroduce ourselves, by exchanging first names. How modern we thought we were! But, as Deb Hull has astutely observed, Don

taught me the nourishing power of respect and courtesy, particularly when an older person offers it to someone younger. … He called me ‘Miss Hull’ for years, and he introduced me to his colleagues and his other students in a way that suggested I might be someone they would benefit from knowing. To the girl from the outskirts of Frankston with a near-crippling case of imposter syndrome, it was an enormous gift. It started to change the way I saw myself. Now I try to extend it to others.[38]

Don was also generous with his professional connections. When Dolly was looking for part-time work, he introduced her to Frank Strahan (1930–2003), University Archivist at The University of Melbourne Archives. Based on her palaeographic skills and doctoral studies in British History, she landed a position.

Don could also rise to the occasion to fill an unforeseen breach. When a scheduled Civil War guest lecturer failed to appear, Don simply walked up to the front of the Old Law Lecture theatre, with its raked floor, wrote a brief outline of what he intended to cover on the chalkboard, and proceeded to give the lecture. He informed the students that a list of references would be pinned to his office door on the third floor of the John Medley Building later that day. A brief interruption in service was diplomatically and seamlessly resolved with minimal fuss and maximum effect. His tutors sat in awe, knowing exactly what had happened, while the undergraduates remained none the wiser.

Don’s intellectual range and rigour were the central pillars and abiding features of his engagement with his students. In exams held at the Exhibition Buildings he would walk along the rows of desks, approaching nervous students, and answering any last-minute questions. Professor Alex Walsham remembers another occasion on which he let down his guard:

In a rare moment of affection from a formal man … I remember standing in the corridor of the John Medley building waiting for an oral examination for Charles Zika’s course. I must have looked very anxious, because he gave me an avuncular hug to give me encouragement.[39]

Don’s formality could be matched by his humour. Don recounted walking around the department all morning with baby-vomit down the back of his jacket. Before coming to work he had been nursing his son, Rod. It was one of the office staff that pointed out the baby’s embellishment, for which Don was very grateful. On another occasion, Dolly remembers a young Sarah sitting in his office colouring in unicorns during a postgraduate supervision. His former students also recount fond visits to the Kennedy clan either in Morrah Street, Parkville, or in the UK while on sabbatical, and the warm welcomes they received. We would now call this a work/life balance.

Dr Geoffrey Smith’s MA and PhD were supervised by Don. Some of his supervisions took place during their time in London together in the early 1990s. “The sessions were exhausting but enormously stimulating” and he “learned how to write history”.[40]

Don’s postgraduates would go on to national, and international success. For example, Professor Patricia Crawford (1928–2008), University of Western Australia, was the international feminist historian who focused on women’s lives in seventeenth-century England and published prolifically on these themes. Professor John Adamson, Peterhouse, University of Cambridge, author of The Noble Revolt: The Overthrow of Charles I (2009) was another.

Don Kennedy’s scholarship was published throughout his career. His earliest publications, however, were his poetry, first published in the Melbourne University between 1950 and 1953: Dove, Into Darkness Fly (1950); The Morning Start Rev. 11, 28, Mercury in Glory and Love Unspoken (1951); Sonnet (1952); and Sonnet (1953). Publications based on his PhD appeared in The English Historical Review, the Mariner’s Mirror, and Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand. He published ‘The Jacobean Episcopate’ in The Historical Journal, in which he took issue with Hugh Trevor-Roper. His monograph, The Security of Southern Asia was published in the Studies in International security series by Chatto & Windus in 1965.

Don also published chapters on foreign affairs, foreign policy, and military security and strategy in southeast Asia. His chapter, ‘Australian Policy Towards China’, appeared in Volume 3 of Australia in World Affairs, edited by Professor Gordon Greenwood (1913–1986), University of Queensland, and Norman Denholm Harper (1906–1986), History, University of Melbourne.[41] In 1969, Don’s chapter, ‘The Debate on a Distinctive Australian Foreign Policy’, appeared in Max Teichmann (ed.) New Directions in Australian Foreign Policy (Middlesex: Penguin).

Publications co-authored and co-edited with his students would also bookend his publishing life. He edited Grounds of Controversy: Three Studies in Late 16th and Early 17th century English Polemics (1989), which included essays by Diana Robertson (1948–1992) and Alexandra Walsham, as well as himself. Fittingly, his last publication in 2015, discussed below, was also with his students.

Publications co-authored and co-edited with his students would also bookend his publishing life. He edited Grounds of Controversy: Three Studies in Late 16th and Early 17th century English Polemics (1989), which included essays by Diana Robertson (1948–1992) and Alexandra Walsham, as well as himself. Fittingly, his last publication in 2015, discussed below, was also with his students.

“To commemorate the gift by Richard Blackwell of the one millionth volume to the [Melbourne] University Library collection” of Thomas Wilson’s 1570 translation of Demosthenes’ Olynthiacs and Philippics from Blackwell’s Rare Books in Oxford, Don and KJ McKay published two essays. The publication was An Appreciation of Thomas Wilson’s 1570 Translation of Demosthenes’ Olynthiacs and Philippics (Melbourne: University of Melbourne Library and the Friends of the Baillieu Library, 1982).[42] Don’s essay provided ‘The Historical Perspective’ and KJ McKay’s essay gave ‘The Literary Perspective’.

Don’s edited collection Authorised Histories (1985) contained contributions by himself, Ron Ridley, Anne Gilmour-Bryson, Charles Zika, Deborah Stephan, Chris Healy, Donna Merwick and Alison Patrick (1921–2006). Shortly thereafter, Don took on a commission from Macmillan to write a textbook on the English Civil War for their ‘British History in Perspective’ series, edited by Jeremy Black. The call of research and writing saw him dividing his time between increasing family responsibilities in order to support Bev in her new career in Law, as well as completing his commissioned book. Of this time, Don said:

Don’s edited collection Authorised Histories (1985) contained contributions by himself, Ron Ridley, Anne Gilmour-Bryson, Charles Zika, Deborah Stephan, Chris Healy, Donna Merwick and Alison Patrick (1921–2006). Shortly thereafter, Don took on a commission from Macmillan to write a textbook on the English Civil War for their ‘British History in Perspective’ series, edited by Jeremy Black. The call of research and writing saw him dividing his time between increasing family responsibilities in order to support Bev in her new career in Law, as well as completing his commissioned book. Of this time, Don said:

I particularly recall writing the section on the breaking of the Royal Seal in 1646 by a smith in the presence of both Houses of Parliament. I still regard this was one of the greatest iconoclastic moments in English History, symbolizing the transfer of power occasioned by the Civil war.[43]

The manuscript was completed seven years after his retirement, and the book published as The English Revolution, 1642–1649 in 2000, a culmination of his teaching and research in this field. A hybrid between a survey and an essay, it bore the hallmarks of his passions and preoccupations as a scholar of this tumultuous period. It focused on the growing divisions between the King, Parliament and the army, and the fissures within the latter that proved so momentous in 1646–1647.

The chapter on the Putney debates gave full expression to his conviction that they not only open a window in the radical mentality of the era, but stand as a critical juncture in English political history per se. The righteous biblical avenger Phineas also appears.

The chapter on the Putney debates gave full expression to his conviction that they not only open a window in the radical mentality of the era, but stand as a critical juncture in English political history per se. The righteous biblical avenger Phineas also appears.

By contrast, the book says comparatively little about the King’s trial. Nor, despite its provocative title – a rather deliberate rejection of the revisionism that then prevailed – did it engage with the historiographical debates about the origin and nature of the Civil Wars that were raging around it.

This was never Don’s priority; what he sought instead was to capture the voices and penetrate the mysteries of the seventeenth century itself.

By 2010, with both Bev’s encouragement and Rod’s assistance, Don returned to his longstanding research project, The Time of Jacob’s Troubles. Although this work would remain unpublished as a whole, it encapsulated the scope and range of Don’s research into Puritan typology in seventeenth-century England. This work was concerned with the concept of typology as “the interpretative interaction between the Old and New Testaments of the Bible”. As Don observed, “the idea of the book was not so much to explain this concept as to trace the typological significance of key figures such as Jacob, Moses and Phinehas in the evolution of the Civil War and to capture the metaphoric richness and density of its linguistic embodiment”.[44]

The joys of this research endeavour were multiple: “I enjoyed the long hours of collaboration with Bev (and the fewer hours of collaboration with Rod) and its creative outcomes”. What is more, “I also enjoyed getting out my old reference books to re-trace old paths and the intensity of re-engaging with Old Testament history and its Puritan exegesis.”[45] The landscape of early modern research had changed dramatically. As Don recalled on re-entering the research world: “to be frank it was a rather gruelling exercise, but I did enjoy the reconnection with academia and the opportunity to re-immerse myself in the sermons of the Long Parliament for the major part of each day”.[46] The technological advances in access to printed primary sources through research databases also impressed him greatly:

it was both disconcerting and exhilarating to find that materials I had painstakingly sourced in the British Library and recorded through an extensive card index were now readily available through Early English Books Online and able to be keyword-searched! The world of my early research had been turned upside down.[47]

The phrase he chose had resonance in the period itself: it described the bewilderment contemporaries felt as settled assumptions and structures were challenged, dismantled and reconstituted against the backdrop of the Civil War, regicide and Interregnum.

To his regret, Don’s volume on Puritan typology in seventeenth-century England did not reach print. One chapter, however, was published in 2015 as ‘Holy Violence and the English Civil War’, part of a Parergon Special Issue entitled Religion, Civil War and Memory, edited by his students Dolly MacKinnon, Alexandra Walsham and Amanda Whiting. This volume also contained essays by Don’s former students Patricia (Trish) Crawford (1928–2008), Geoffrey Smith, Damian Powell, John Reeve and Wilfrid Prest.

Trish Crawford, knowing full-well that she would not live to see Don’s volume published in 2015, penned her gratitude in both her letter expressing her willingness to be part of this collection and in her essay dedication: “I wish to thank my friends who have helped with this article, especially Dr D.E. Kennedy who first introduced me to the idea of blood guilt.” An earlier version of Trish’s article had first appeared in The Journal of British Studies, 16.2 (1977), 41–61. On re-reading Don’s contribution to the Festschrift, Wilf Prest “was once again very impressed by the seriousness of his scholarship, the clarity and force of his writing, the skill with which he brings out the power of the preachers to mould the minds and actions of their auditory”.[48] It was with authority that Don spoke.

As Don’s last postgraduate student, Dolly found a safe harbour in the history department under his guidance, among people who would become lifelong friends and colleagues. She concludes:

I would not have gone on to be an Associate Professor if I had not met and been taught by him. On one of our many farewells, at the University, this one outside the Old Law Quad, he wished me God’s speed, before turning toward the John Medley Building. This is how I see him still. As the generations that follow on, we carry you in our thoughts, actions, and deeds, Dr Kennedy. God’s Speed.

Dolly MacKinnon

Alexandra Walsham

Amanda Whiting

Wilf Prest

1 August 2022

Publications

Lost works

Passion Plays.

Contributions to Present Opinion. Melbourne University Arts Association.

Manuscripts

MA Thesis, The University of Melbourne, 1952

D.E. Kennedy, ‘Some Aspects of Causation in History: An Inquiry into the Logical Efficacy of The Causal Presupposition in Historical Explanation’.

PhD Thesis, Trinity College, Cambridge, 1956

D.E. Kennedy, ‘Naval administration during the Civil War and the Fleet Revolt of 1648’

Supervised by Professor Brian Wormald (Peterhouse).

D.E. Kennedy, Memory Jar [private unpublished memoir, Kennedy Family], c2018.

Prizes

Julian Corbett Prize Essay in Modern Naval History, University of London, 1958.

Essay: Parliament and the Navy, 1642–1648.

Printed Poetry

D.E. Kennedy, ‘Dove, Into Darkness Fly’, The Melbourne University Magazine, edited by Ken Inglis and Murray Groves, July (1950), p. 43.

D.E. Kennedy, ‘The Morning Star Rev. 11, 28’, The Melbourne University Magazine, edited by Lee Kok Liang and Gareth Moorhead, July (1951), p. 72.

D.E. Kennedy, ‘Mercury in Glory’, The Melbourne University Magazine, edited by Lee Kok Liang and Gareth Moorhead, July (1951), p. 73.

D.E. Kennedy, ‘Love Unspoken’, The Melbourne University Magazine, edited by Lee Kok Liang and Gareth Moorhead, July (1951), p. 74.

D.E. Kennedy, ‘Sonnet’, The Melbourne University Magazine, edited by James Griffin and Vincent Buckley, July (1952), p. 26.

D.E. Kennedy, ‘Sonnet’, The Melbourne University Magazine, edited by Evan Jones and John Lawry, July (1953), p. 76.

D.E. Kennedy, ‘Love Song’, The Trinity Magazine (May 1954), p. 14.

D.E. Kennedy, ‘Love Unspoken’, Granta, vol. LXVIII, no. 1154 (30 April 1955), p. 24.

D.E. Kennedy, ‘Sonnet’, Granta, vol. LXVIII, no. 1154 (30 April 1955), p. 24.

Academic Articles, Books and Book Reviews

D.E. Kennedy. (1960) ‘Naval Captains at the outbreak of the English Civil War’, The Mariner’s Mirror, vol. 46, no. 3: 181–198.

D.E. Kennedy. (1961) Summary of Julian Corbett Prize Essay 1958: Parliament and the navy, 1642–1648; problems of discipline and politics in the fleet during the Civil War, Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, vol. 34, no. 89, (May): 100–102.

D.E. Kenney. (1962) ‘The English Naval Revolt of 1648’, The English Historical Review, vol. LXXVII, issue CCCIII, (April): 247–256.

D.E. Kennedy. (1962) ‘The Establishment and settlement of the Parliament’s admiralty, 1642–48’, The Mariner’s Mirror, vol. 48, no. 4: 276–291.

D.E. Kennedy. (1962) ‘The Jacobean Episcopate’, The Historical Journal, vol. 5, no. 2: 175–181.

D.E. Kennedy. (1963), review of Ralph Davis, The Rise of the English Shipping Identity in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. London: Macmillan, 1963), in Business Archives and History, vol. 3, no. 2: 227–229.

D.E. Kennedy. (1964) ‘The Crown and the common seaman in early Stuart England’, Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand, vol. 11, no. 42: 170–177.

D.E. Kennedy. (1964), review article, ‘The Wood and the Trees: The Philosophical Development of R.G. Collingwood’. Australian Journal of Politics and History, vol. 10, no. 2: 245–248.

D.E. Kennedy. (1965), review of J.R. Powell and E.K. Timings (eds.). Documents Relating to the Civil War: 1642–1648 (London: The Navy Records Society, 1963), in The English Historical Review, vol. LXXX, Issue CCCXVII, (October 1965): 839–840.

D.E. Kennedy. (1965) The Security of Southern Asia (London: Chatto and for the Institute for Strategic Studies).

D.E. Kennedy. (1966), review of Christopher Hill, Intellectual Origins of the English Revolution (1965): ‘Dealing with the steam: Christopher Hill and the intellectual origins of the English Revolution’, Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand, vol. 12, no. 46: 297–303.

D.E. Kennedy. (1968) ‘Australian Policy Towards China’, vol. 3, pp. 397–415, in Australia in World Affairs, 4 vols. edited by Gordon Greenwood and Norman Harper.

A.L. Burns, S. Encel & D.E. Kennedy. (1969), review of Hugh Stretton, The Political Sciences: General Principles of Selection in Social Science and History, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, in ‘The Political Sciences: A symposium’ Section (iii) Sacred Geese and Holy Cows, Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand, vol. 14, no. 53: 73–79.

D.E. Kennedy. (1972) review of ‘Foreign Policies in South Asia. Edited by S. P. Varma and K.P. Misra. (Bombay, Calcutta, Madras, New Delhi: Orient Longmans Limited, 1969. Pp. iv, 403, American Political Science Review 66, no. 4: 1418–20.

D.E. Kennedy. (1969) ‘The Debate on a Distinctive Australian Foreign Policy’, in Max Teichmann (ed.) New Directions in Australian Foreign Policy (Middlesex, England: Penguin), pp. 65–76.

Hugh Stretton, L.C.F. Turner & D.E. Kennedy. (1974) ‘The causes of war’. Historical Studies 16, no. 62: 104–11.

D.E. Kennedy. (1974), review of J. Thirsk and J.P Cooper (ed) Seventeenth century Economic Documents (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), in Australian Economic History Review, vol. 14, no. 1: 82–83.

D.E. Kennedy and K.J. McKay. (1982) An appreciation of Thomas Wilson’s 1570 translation of Demosthenes’ Olynthiacs and Philippics (Melbourne: University of Melbourne Library and the Friends of the Baillieu Library).

D.E. Kennedy, Diana Robertson, and Alexandra Walsham (eds) (1989). Grounds of controversy: three studies in late 16th and early 17th century English polemics (Parkville: History Department, The University of Melbourne, 1989).

D.E. Kennedy (ed). (1995) Authorized pasts: essays in official history (Parkville: History Department of The University of Melbourne).

D.E. Kennedy. (2000) The English Revolution, 1642-1649. Houndmills, England and New York: Macmillan Press, and St. Martin’s Press.

D.E. Kennedy. (2015) ‘Holy Violence and the English Civil War’, Parergon 32, no. 3: 17–42, in Special Issue: ‘Religion, Civil War and Memory’, edited by Dolly MacKinnon, Alexandra Walsham and Amanda Whiting.

Endnotes

[1] With much appreciation and thanks to the Kennedy family, Sarah, Eliza, Susannah and Roderick for their family insights, photographs, and access to DEK’s own unpublished private memoir, Memory Jar, c2018. Thanks also to Lis Grove, Amanda Whiting and Dolly MacKinnon for permission to reproduce their photographs. The covers for the Melbourne University Magazine are reproduced with permission of the Special Collections, Baillieu Library, University of Melbourne. This article is based on the funeral eulogy delivered by Honorary Professor Dolly MacKinnon, at the request of Don and his family, at Trinity College Chapel, Parkville, Victoria, 4 November 2021. With contributions by Don’s former students and colleagues: Professor Alexandra Walsham, Professor of Modern History, University of Cambridge; Associate Professor Amanda Whiting, Associate Director (Malaysia), Asian Law Centre, Melbourne Law School, University of Melbourne; Dr Mark Nicholls, Senior Lecturer in Cinema Studies, School of Culture & Communication, University of Melbourne; Dr Deb Hull, Executive Officer, History Teachers’ Association of Victoria; Dr Damian Powell, Former Master, Janet Clarke Hall, University of Melbourne; Professor Wilfrid Prest, Professor Emeritus of History and of Law, Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide; Dr. Geoffrey Smith; Professor Tony Coady, Professor Emeritus Historical & Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne; Dr John Reeve, Honorary Senior Lecturer in History, UNSW; Professor Ronald T Ridley, Professor Emeritus Historical & Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne; Professor Charles Zika, Honorary Professor, School of Historical & Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne; Associate Professor Dolly MacKinnon, Honorary Associate Professor, School of Philosophical and Historical Studies, University of Queensland; the late Professor Patricia Crawford (1928–2008), University of Western Australia. This piece also draws on Parergon 32.3 (2015): 17–42. We are also grateful for facts and clarification provided by Emeritus Professor John R Poynter, Ernest Scott Professor of History at the University of Melbourne (1966–1975) and Deputy Vice–Chancellor (1979–1990), Honorary Professor Pat Grimshaw, University of Melbourne, Emeritus Professor Clive More, University of Queensland, and Dr Barbara Pertzell.

[2] D.E. Kennedy, unpublished private memoir, Memory Jar, c2018, 42.

[3] Ibid., 36.

[4] Ibid., 37.

[5] D.E. Kennedy, ‘Some Aspects of Causation In History: An Inquiry into the Logical Efficacy of the Causal Presupposition in Historical Explanation’, Supervised by Arthur Lee Burns (MA Thesis, The University of Melbourne, 1952). University of Melbourne, Baillieu Library, Special Collections, UniM Bund SpC/T KENNEDY.

[6] Kennedy, Memory Jar, 43.

[7] Wilf Priest, Parergon 32:3 (2015): 8–9.

[8] Ron Ridley, Email reflection sent to Dolly MacKinnon, 1 November 2021.

[9] Mark Nicholls, Email reflection sent to Dolly MacKinnon, 8 November 2021.

[10] Ron Ridley, Email reflection sent to Dolly MacKinnon, 1 November 2021.

[11] Kennedy, Memory Jar, 83.

[12] Ibid., 84.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Nicholls, Email reflection.

[15] Don Kennedy, Parergon 32:3 (2015): 15.

[16] Kennedy, Memory Jar, 60.

[17] Ibid., 131.

[18] Tony Coady, Email reflection sent to Dolly MacKinnon, 6 July 2022.

[19] In Fay Anderson and Stuart Macintyre (eds.) The Life of the Past: The Discipline of History at The University of Melbourne (Melbourne: The Department of History, 2006): John Poynter, ‘Wot Larks To Be Abroad: The History Department, 1937–71’, 39–92, quoted at 78–79; Charles Zika, ‘Medieval and Early Modern European History’, 173–206, quoted at 183; Charles Sowerwine, ‘Modern European History in the Antipodes’, 207–234.

[20] Kennedy, Parergon 32:3 (2015), 15.

[21] Ridley, Email reflection.

[22] Helen Penrose, Email reflection sent to Dolly MacKinnon, 30 October 2021.

[23] Alex Walsham, Email reflection sent to Dolly MacKinnon, 31 October 2021.

[24] Damian Powell, Parergon 32:3 (2015), 7.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Damian Powell and Amanda Whiting, Parergon 32:3 (2015), 8 and 13.

[27] Whiting, Parergon 32:3 (2015), 13.

[28] Deb Hull, Email reflection sent to Dolly MacKinnon, 31 October 2021.

[29] Dolly MacKinnon, Funeral Eulogy, 4 November 2021.

[30] John Reeve, Parergon 32:3 (2015), 10.

[31] Nicholls, Email reflection.

[32] Whiting, Parergon 32:3 (2015), 13.

[33] Reeve, Parergon (2015), 10.

[34] Walsham, Email reflection.

[35] Nicholls, Email reflection.

[36] Charles Zika, Parergon 32:3 (2015), 13.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Hull, Email reflection.

[39] Walsham, Email reflection.

[40] Geoffrey Smith, Parergon 32:3 (2015), 10.

[41] Poynter, ‘Wot Larks to Be Abroad’, 72.

[42] The printed dedication appearing on the inside cover of the volume.

[43] Kennedy, Memory Jar, pp. 183–184.

[44] Ibid., 202–203.

[45] Ibid., 202.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Wilf Prest, Email reflection.

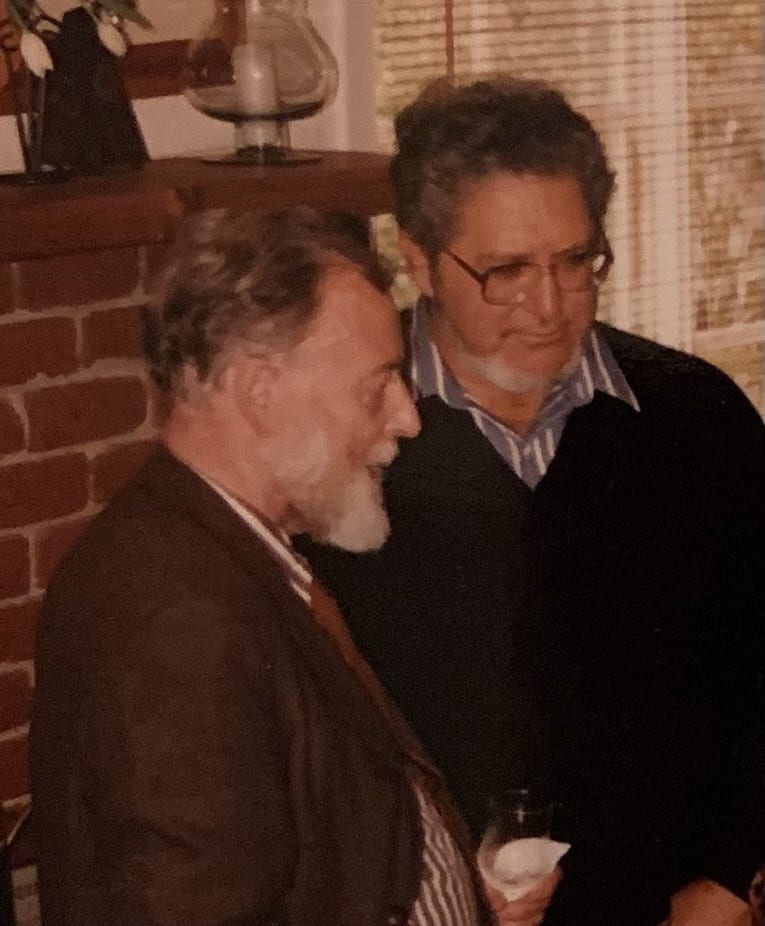

Feature image: Don Kennedy before his retirement, 1993. Courtesy, the Kennedy Family